“Intimacy is too often confined with matters of love; yet the word belongs more to trust, to faith. It denotes an act of revelation found in the simple gesture of sharing; bringing that which was previously hidden out from the shadows and into the light. In this exhibition, the artworks chosen explore intimacy in both their content and their form. They touch on universal themes – like birth and love and death – but also on other more singular intimacies; personal histories, dreams and desires. The works reflect on self- intimacy, experienced in solitude, and the intimacy shared between us, be it romantic or platonic, familial or fleeting. There is, too, intimacy of familiar spaces, spaces we inhabit in both the world and in our minds. And then, there is the intimacy of objects, and our relationships to them; a cherished photograph, clothes left lying on the floor, a coffee half drunk, now gone cold, a letter hidden in a bottom drawer. And always an implied subject, who has held and touched these objects, so that each becomes a metonym for something, or someone, else.” – reads the introductory paragraph of the essay on the group show titled The Art of Intimacy by Lucienne Bestall.

Curated by SMITH’s own Jana Terblanche, Close Encounters, “…encompasses many intimacies. Intimacy between friends, family and even yourself. An ‘encounter’ extends beyond romantic love, and opens the show up to a certain type of multiplicity…” she tells me in response to the exhibition title.

Terblanche explains further that, “The curatorial strategy seeks to make connections, and guide the audience to experience many versions of intimacy, but not to be too definitive in fixing its meaning.”

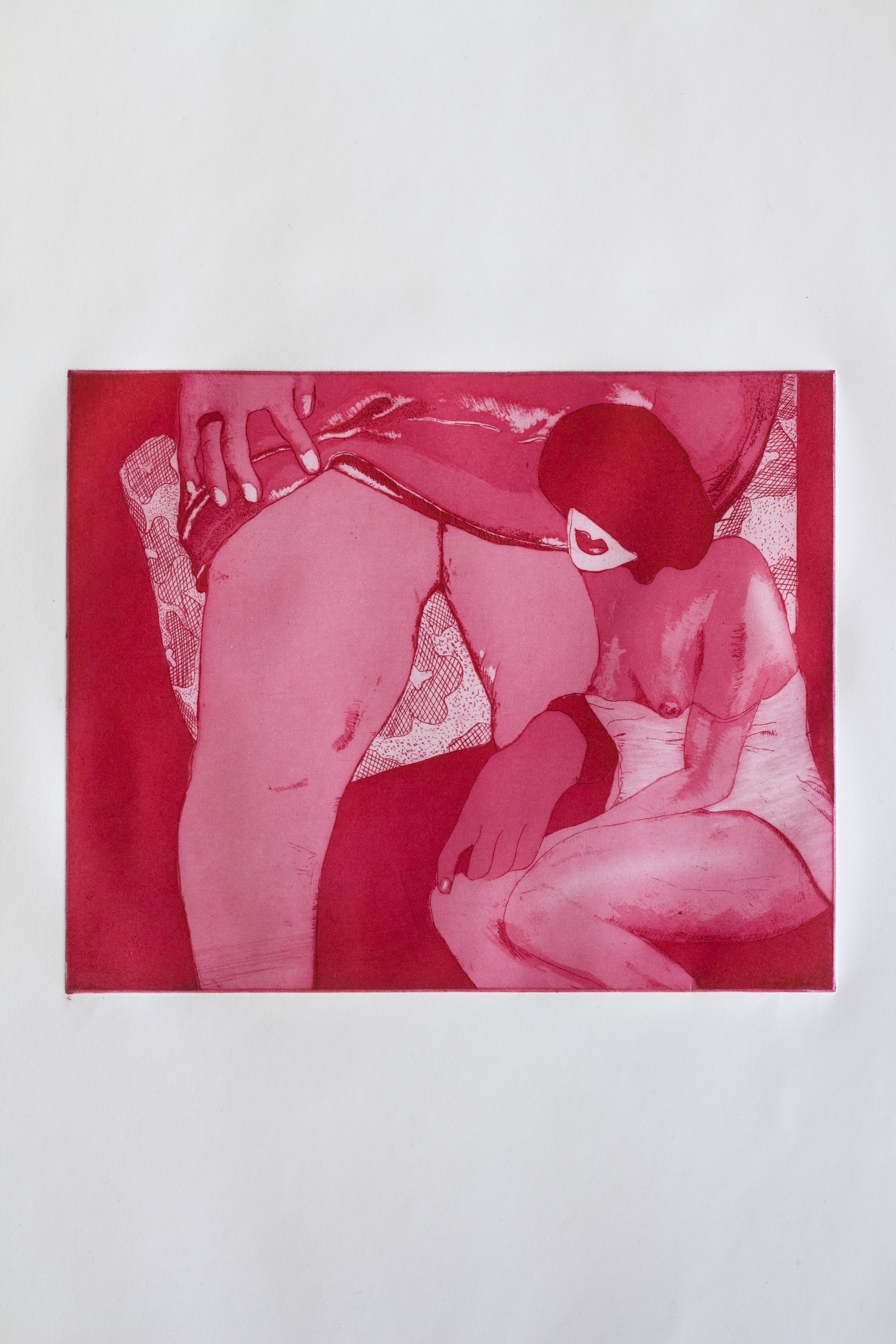

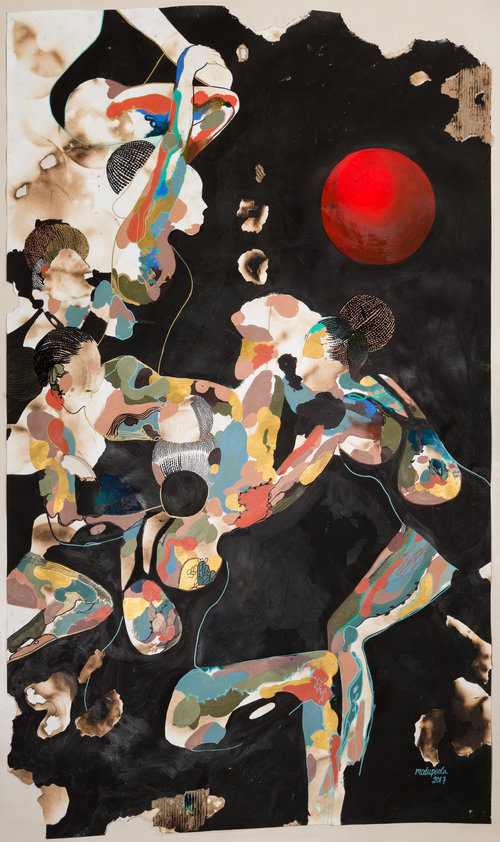

Interpretation, voyeuristic in its nature, peeks into private scenes in the works of Olivié Keck, Daniel Nel and Banele Khoza. As the viewer uncovers that which is hidden, they are confronted with the image of a sleeping woman with a bloodstain forming between her legs; with figures in a bedroom – dressing or undressing. A nude man cradles his foot in another work. As Bestall points out, the human shapes portrayed on these canvases appear to be unaware of their viewer, unaware of being watched. They are “…absorbed in their own worlds and insensible to ours. From this vantage, we become privileged viewers; seeing yet unseen.”

Boy in Pool and Creepy Noodle by Strauss Louw presents as photographic montages reflecting on ideas surrounding sensuality and sexuality. The images’ quality can be compared to a fever dream, confused, stripped down. A recurring element in both frames is that of water. Water which is fluid and evokes connotations around spiritual cleanliness, the metaphorical washing away of sin; a baptism that promises new life, a new beginning. The images that reflect one another and in turn speak to one another show an intimacy that extends beyond photographic paper. The signifier, pool noodles and topless male torsos, signify more than the visual cues the artist brings to the fore. Bestall writes, “For him, the gesture of photographing is itself an act of intimacy; the silent communion between the subject and artist shared for only the briefest moment.”

Moments of grave intimacy equally take hold in this group show appearing as recollections of space lost, contemplations on censorship, erasure and that which is muffled. A weapon uncovered from the quite recesses of a grandmother’s bed.

Returning to the intimacy of childhood, Thandiwe Msebenzi, Sitaara Stodel and Morné Visagie use film, collage and photographs to convey their meaning. Loss, longing and distance oozing from each pigment.

Tapping into the darker avenues of the twisted mind, Michaela Younge and Stephen Allwright craft peculiar scenes of nightmarish fantasy. Younge’s work made from merino wool and felt, bring together eroticism, violence, sensuality and abjection. In this world of felt imagination nude figures, skulls, a doll’s head, the American Gothic and a lawnmower coexist on the same material plane.

The intimacy of banal objects is considered by artists Gitte Möller and Fanie Buys. Buys’ Unknown Couple at their Wedding (muriel you’re terrible) is a painting of a found image depicting a bride and groom about to cut into their wedding cake. The familiarity of the scene is nostalgic as it is found as such in endless family photo albums.

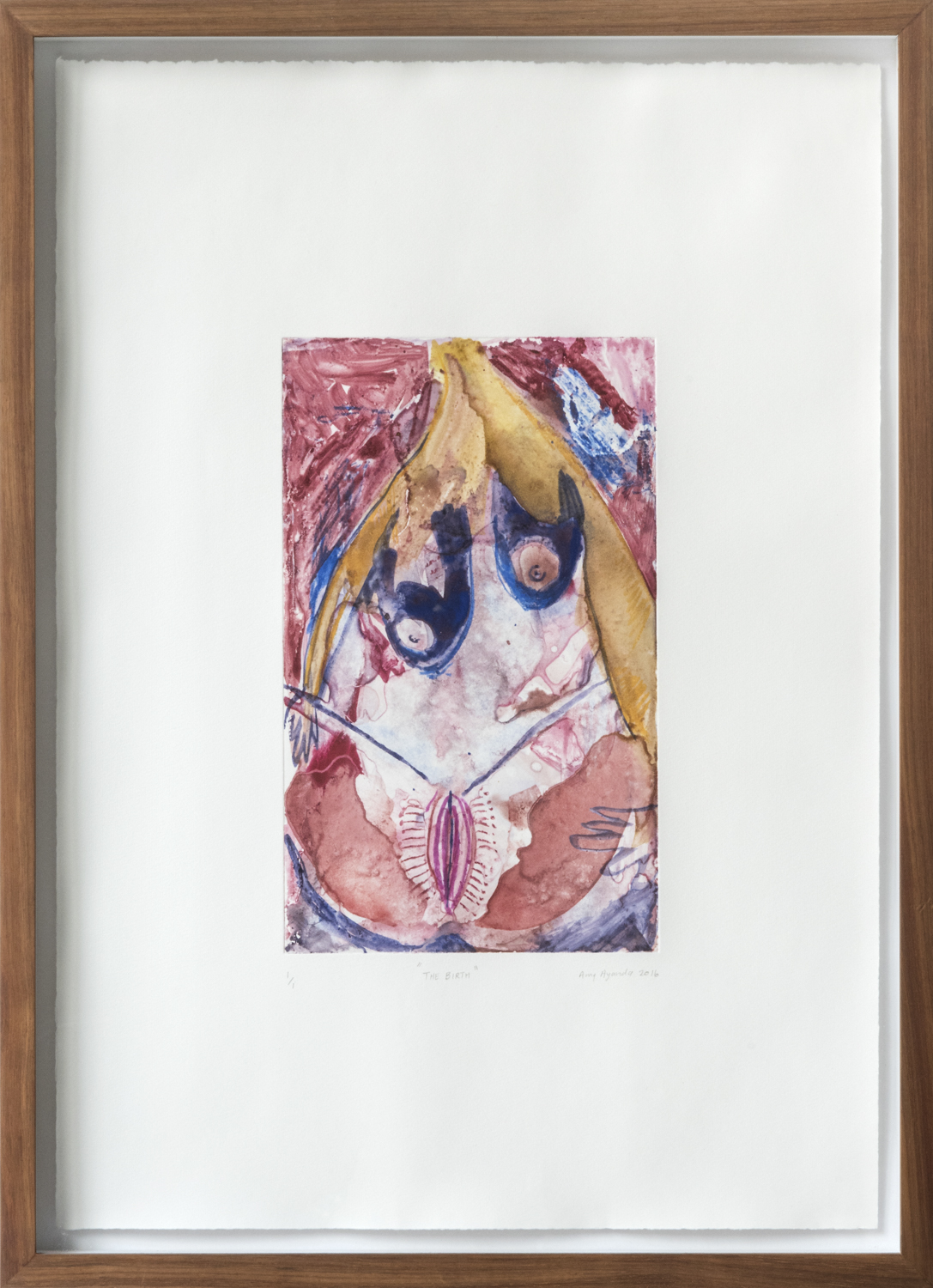

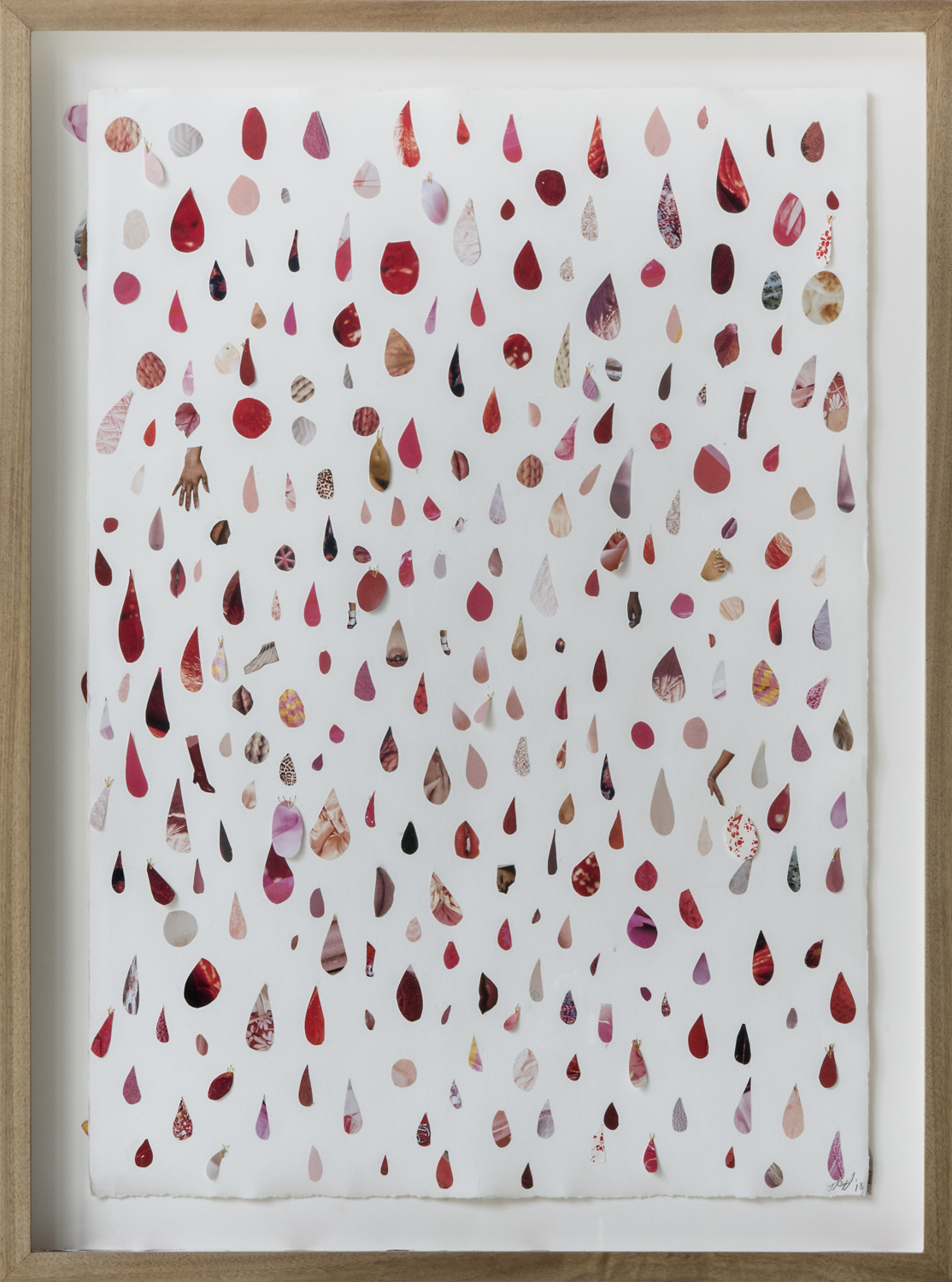

Pairing the personal with the universal Amy Lester uses a monotype of a faceless woman that draws parallels with the Venus of Willendorf and other objects and images of fertility. Alongside hangs a photograph of the artist’s birth. This iteration of familial intimacy explores birth and the archetypal Mother figure.

The viewer is moved from private bedroom scenes to depictions of violence, from a clear subject to an underlying layer of meaning, invited to engage with the scale of works, the theme of intimacy follows distinct threads. “Yet the works exhibited all share the same vulnerability. Something previously hidden is revealed; a secret spoken aloud, a memory described, a dark dream recalled. Such is intimacy, a word bound not to love, nor to the erotic. But rather, a word that denotes a certain knowledge, a privileged insight into the private life of another – another figure, another object, another place. Where some intimacies are lasting, others are only momentary; where some are apparent, others are not.” Bestall ends off.

The interdisciplinary group show Close Encounters will run from the 4 July – 28 July 2018.

Join SMITH Gallery on a walkabout of the show on Saturday the 21st July at 11h00.

Exhibiting artists include: Stephen Allwright, Fanie Buys, Grace Cross, Claire Johnson, Jeanne Gaigher, Jess Holdengarde, Olivié Keck, Banele Khoza, Amy Lester, Strauss Louw, Sepideh Mehraban, Nabeeha Mohamed, Gitte Möller, Thandiwe Msebenzi, Daniel Nel, Gabrielle Raaff, Brett Charles Seiler, Sitaara Stodel, Marsi van de Heuvel, Anna van der Ploeg, Morné Visagie, Michaela Younge