KutalaChopeto‘s exhibition opened at The Point of Order on World Refugee Day. Teresa Firmino and Esenje Helena Uambembe are an art duo who work collaboratively under the name KutalaChopeto. Their collective practice began in 2016. For this latest project, they focused their research on different communities based predominantly in the North West and Gauteng province – reconsidering stories of seemingly forgotten and disenfranchised communities. KutalaChopto collaborated with curator Maren Mia du Plessis, visual artists Loyiso Mzamane and Setumo-Thebe Mohlomi and Christiano Selmo Uambembe.

Born from the rupture of the Angolan Civil War and the perceived ‘threat’ of communism, the South African Apartheid government sought to recruit and re-train a select group of FNLA (National Liberation Front of Angola) troops. The secret division were known as the 32 battalion or “the terrible ones”- most South Africans were unaware of its existence until it was disbanded in 1993. Many of these men were already married or from refugee camps. Those who were unmarried were encouraged to wed Angolan womxn in order to produce more soldiers. Teresa described how, “the system itself was violent, so it continued to produce violent bodies.”

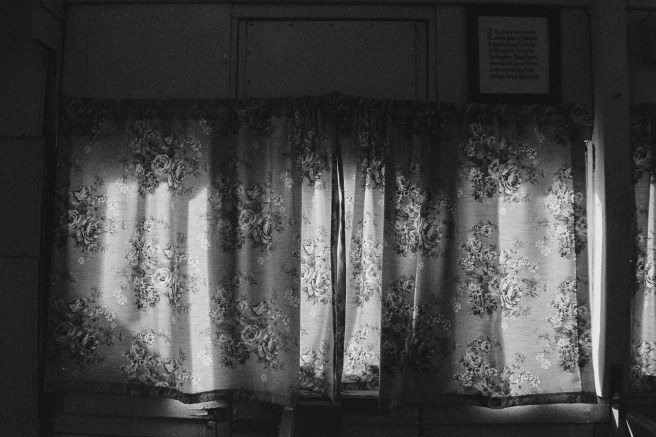

The soldiers were promised land in exchange for fighting alongside the South African government and therefore were relocated between 1988-91 to Pomfret in the North West. The desert town has become increasingly abandoned – utilities have been systematically shut down by the government as a means to vacate the town under the guise of a safety breach from asbestos poisoning.

KutalaChopeto’s project is centred around the community itself, specifically the womxn whose voices have been historically silenced. The collective was interested in how they ended up in the camp as well as their experiences with living with men who have undergone war and tragedy. The legacy of that trauma appeared to manifest through the normalisation of violence within the larger community. The duo sought to collect histories and translate them visually. Their chosen mode of rewriting or reconstructing history extends beyond documenting the past and interrogates historically held narratives – through a deconstruction and reengagement of fragmented stories previously neglected. KutalaChopeto locate this narrative within an intra-continental perspective between Namibia, Angola and the Border Wars during the height of Apartheid and also examine what remains. “Home is not a place anymore. It becomes the people you are with.”