When knee deep into Women’s Month we tend to forget to ask ourselves ‘how do I intend on keeping the conversation going?’ This year has seen an especially politically charged Women’s Month in South Africa. This month was prefaced by the action during the President Jacob Zuma’s election briefing at the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) being disrupted by the silent protesters, Amanda Mavuso, Naledi Chirwa, Tinyiko Shikwambane and Simamkele Dlakavu.

Through their protest these Gender activists’ were sparking necessary discussions surrounding gender violence and women’s bodies. Though triggering at times, one of the hardest aspects of gender activism is reminding people that these issues of violence against women are not just for discussion during this single month.

Yet its discussion ensures that the discourse surrounding women’s bodies, as triggering and difficult as they may be, continues through the pain. When it is no longer fashionable to do so, at risk of being accused of being a gender instigator, we continue. For me Germaine de Larch has been one such activist who continues this work through the use of his body and his words on his blog.

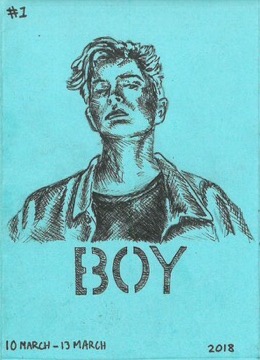

Making invisible bodies Visible

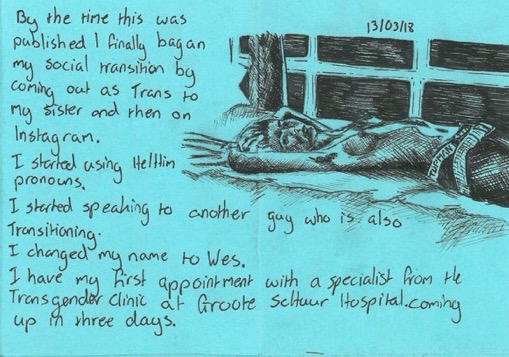

I first saw Germaine on my Facebook page as an update on a friend’s activities who had “liked” a post of his. What first struck me about the post was his honesty. From the get go he was open about his Trans identity, and struggle to find his space amongst his female feminist community. Having been chastised for wanting to become “a man” he was adamant that he would still remain a feminist but one who is conscious of his new male privilege.

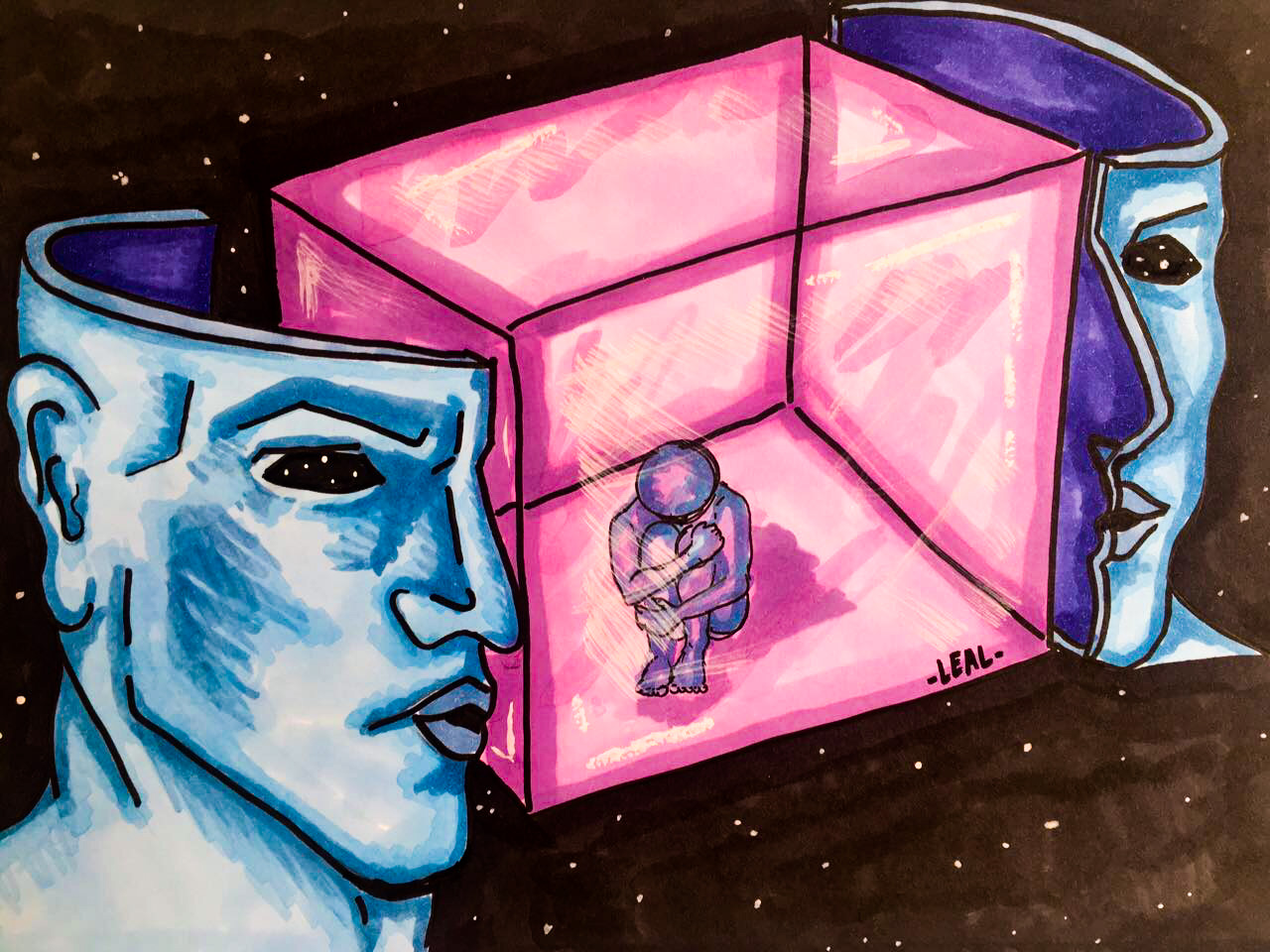

What struck me about his ideas are their complexity and somewhat contradictory nature. Having never felt like a woman but never feeling like being a man, he explains that his gender identity cannot be comfortably placed on either side of the binary. He describes himself as being a non-binary gender queer whose main focus is to move outside of the gender stereotypes. He describes himself as being a proud feminist politically, which is a big deal for him as he does not identify as just Trans but a “trans man”.

Germaine’s ideas on gender challenge the normalised binaries. They do so by his questioning of what it means to be Trans, forcing the concept of ‘non-binary’ to be taken seriously. Germaine is not one for such oversimplified notions of gender and would clearly define himself as one who slips in-between such static notions of such. In an act of ‘intellectual agency’ he understands his new role as a feminist would be one that includes a discussion on his own whiteness and soon to be ‘male privilege’.

It is within this category that he does not identify as a cisgender male and therefore cannot consider his identity as moving from female to male, Trans(ition), binary. For him, non-binary allows one to explore the different genders whilst not being stuck in either. “As an assigned female at birth (AFAB) person I can still go onto testosterone whilst not proclaiming that I want to be a man”. For Germaine the task for non-binary is not the dismissal of a gender reality but rather the exploration of the self, outside of the set boxes of man and woman.

“My images are a conscious choice to tell my own story and collaboratively tell the stories of my community, my city.”

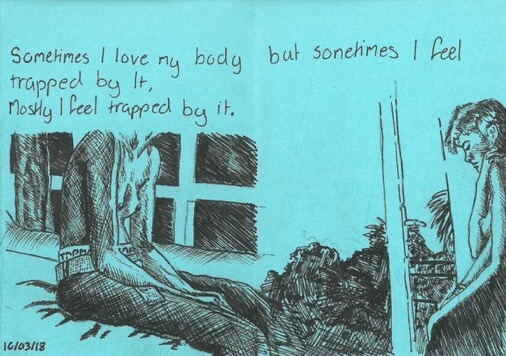

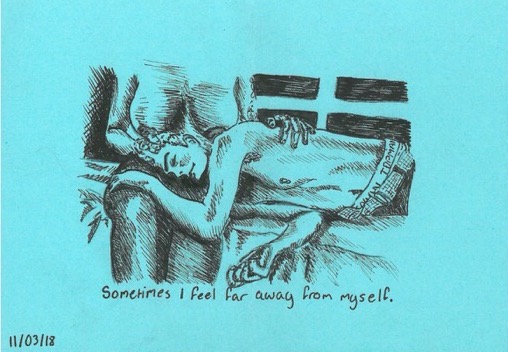

For Germaine a major focus in his work is talking about his own experiences traveling between gender identities as a transgender (Trans) man. Having recently started hormone treatments and experiencing its effects, much of his conversation would be about his physical reactions and how they impact on his understanding of his politics and who he is.

He identifies his work as part of the conversation on Trans visibility, “by being visible for others where others that can’t be visible themselves”. He achieves this through portraiture and an engagingly in-depth blog, both of which offer a glance into Germaine’s Trans journey and a theoretical exploration thereof. It is through his contribution to the discussion on gender that we see his work resonating with a collective (LGBTQI) story.

Activism through Art

His work with photography, starting with self-portraits, would be the beginning of his activist work. Suffering from writer’s block at the time, the medium would be a useful outlet for his ideas. “Making portraits was an intense way of asking questions that you can’t escape. What is your gender? What are its performed rites of passage?”

Through self-portraiture he would perform gender by using props and make-up. He would examine his responses to gender and his own preconceptions of it. “By doing such analysis you can only find out what you are by what you are not. If I am not this blank canvas then what am I?” For him the art process is one of self-exploration. For him the testosterone and tattoos would also be a crucial part of his method of “painting”. His process becomes one of self-examination, of who you are and who you can be. The body becomes the canvas in which one can “play out the roles”.

In his work he also wanted to examine the responses of the viewer engaging with these representations. With his relative safety he is provided the opportunity of showing himself where others have to hide. In being visible he wanted to make the world aware of how we are also vulnerable to troll, those who would also have a lot of negative things to say to her. He shares the responses to his online followers to show them how society can react to Trans individuals. Though many of the responses have been positive there are still a few who would publicly chastise him for being Trans.

A warrior not a survivor

“Not a survivor, a warrior, recreating myself & my body, learning to live life large, one day at a time. Non-Binary Genderqueer”

In his blog he describes himself as “a warrior and not a survivor”. This was done in response to how so much of the discourse surrounding victims of rape are overshadowed as victims. He makes this move to warrior as a conscious political act of reclaiming himself outside the confines of ‘rape victim’. “I took who she could have been, a self lost from the violence. By bringing that person back by engaging with a process of becoming”. This is his act of reclamation, the conscious continuous act of developing oneself.

In dealing with his depression the same act of reclamation is present as it becomes one of also reclaiming a life lost from dealing with depression. “Its about knowing myself, knowing my triggers and weak points so that it’s not just about living with it but living a full life. Reclaiming my life over depression is about not being a victim over something I cannot control.”

Identity is intersectional

The inclusion of sexual abuse and mental illness in his writing is there to shows how complex one’s identity one can be whilst living as Trans. “I am not just Trans, I am all these things and they speak to each other explaining who I am.” In highlighting his Trans identity in writing he aims to challenge the medicalised understandings of Trans and sees these two issues as occurring separately. “I can be sick but also Trans and seek medical treatment. I seek medical help as a human being and not as trans”. Yet he is very much aware of the stigma and prejudice surrounding his LGBTQI community and how their very identity as Trans can actually prevent one from getting adequate treatment.

“My work is thus a collaboration with people and places on a journey of who they are, who are interested in playing with their identities, who want to explore the creative possibilities outside of the stereotypes.”

It’d be easy to forget just how personal the lives of those these theory functions to explain. He whose life, politics and activism cannot be separated from each other. For him these worlds are always in conversation resulting in work that is both deeply personal and furiously conscious.