Cantilevered concrete extends into a crisply lit tower foregrounding the bright cerulean winter sky. Tire treads mark the intersection of an arterial road, the pulse connecting the suburbs of Johannesburg to the heart of the city. Adjacent, a narrow side street reverberates the sounds of lorries and delivery vans. The bustling sidewalk is grounded by rectangular forms – interjected by an iron grate ashtray. Indigenous foliage peppers a raised platform of slate stones. This is the corner occupied by The Point of Order.

The Point of Order operates as a mixed-use project space managed under the exhibitions programme of the Division of Visual Arts at the Wits School of Arts. This year nine students were selected to participate in the Wits Young Artist Award – a prestigious event that aims to provide an exhibition platform for emerging artists. Notions of inherited legacy, gender, sexuality and mapping space were explored throughout the show.

Allyssa Herman is interested in the way knowledge is produced around the kitchen table and domestic space. A kitsch ceramic canine inherited from her grandmother is central to the work A Shrine for my Bitch. “A shrine for my bitch, it’s just that. A shrine for my bitch. My bitch is an embodiment of me, an embodiment of the woman who have passed, who’s ideals live in me…This bitch has been sitting in my grandmother’s home watching me all my life, she deserves a shrine, she deserves to be praised. My bitch is both dead and alive. She is that bitch. We are that bitch. Bow down bitches!” The shrine, arranged with an abundance of fake flowers, family portraits, candles and doilies pay homage to Allyssa’s matriarchal lineage – the veil between life and death.

“I hate doilies. There is something very suspicious about the cleaning, masking, covering, and the needing to impress that comes with being a woman. The passing down of these doilies happens in those moments when mama’ tells me gore ngwanyana o kama moriri; ngwanyana ga a tlhabe mashata; ngwanyana o dula so, ga a tlaralle” says runner-up Lebogang Mabusela. Lebogang’s response to these crocheted signifiers of femininity and ‘black womanhood’ is to reimagine them through a series of monotype prints. “Doilies are used to conceal flawed and plain surfaces in a more decorative way. They are about dignity, integrity and keeping a seductive, elegant and glamorous home even when things are just falling apart slightly, because Abantu bazothini?” Her work tenderly addresses the transference of societal projections on paper.

Cheriese Dilrajh also engages the domestic sphere in her work. “A space can feel foreign to you even if it is your home. It can make you question your existence.” Her installation of suspended sarees adorned with paper plants and a video projection of “alien plants of the Internet” challenges tradition and the notion of inherited culture. “People can be thought of as plants. There are indigenous and alien, each determined which is which by the space it is allowed to flourish and survive in. Plants are interesting to me as they sometimes appear to embody human characteristics. My grandmother would also often transfer plants from her house to our garden.” Her interests extend into decolonising the self – “postcolonial is not only a theory, it is lived and embodied. It is everywhere, and identity becomes distorted and confusing, informing our growth.”

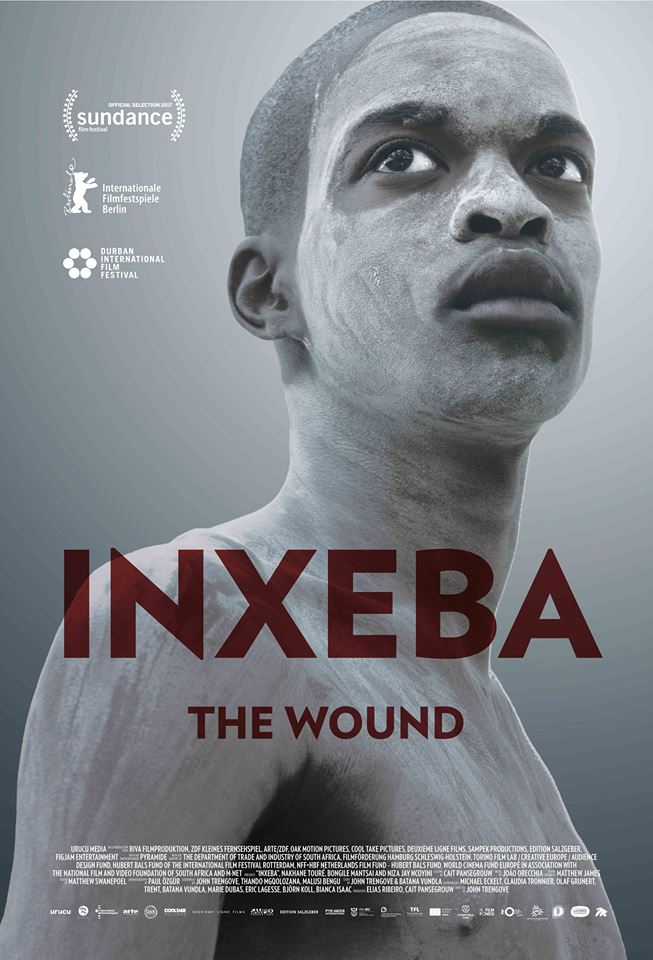

Dominique Watson‘s haunting bed installation is a response to a project created by the SADF during apartheid at the time of the Border Wars. Conscripts classified as homosexual or ‘deviant’ were sent to Ward 22 of the Military Hospital in Voortrekkerhoogte. In this ward they were subject to the ‘conversion’ procedures of electroshock therapy and chemical castration. Dominique discovered documentation of these atrocities in GALA‘s archive – including accounts from patients as well as their families. She describes this, “history as a haunting” whereby the medical gaze approached the queer body as one riddled with disease. The red bedsheet bound around the military-style cot has been stained with institutional ink – signifying the oppressive nature of the establishment.

For his provocative work, Oratile Konopi collaborated with Hip-hop artist Gyre. Oratile’s piece is a visual response to the musician’s single entitled Eat My Ass. “We went about creating an artwork with its own narrative. The narrative of a dinner date in which you would get to know someone, going through two courses but the desert not being eaten rather alluding to the idea that something else is being ‘eaten’.” Oratile explores notions of masculinities central to the identity of black men in his artistic practice – often employing music as a device to create a point of accessibility. The installation offers an opportunity for the audience to engage with the works in a tangible form – adding to what would otherwise be limited to digital interface. Oratile and Gyre use this platform to, “speak on the issues related to gender and sexualities present in the music sonically and extending it visually. We chose the LP format because it speaks to a different moment in time. Complicating the idea that multiple sexualities are something only present in the contemporary moment and did not exist in the past.”

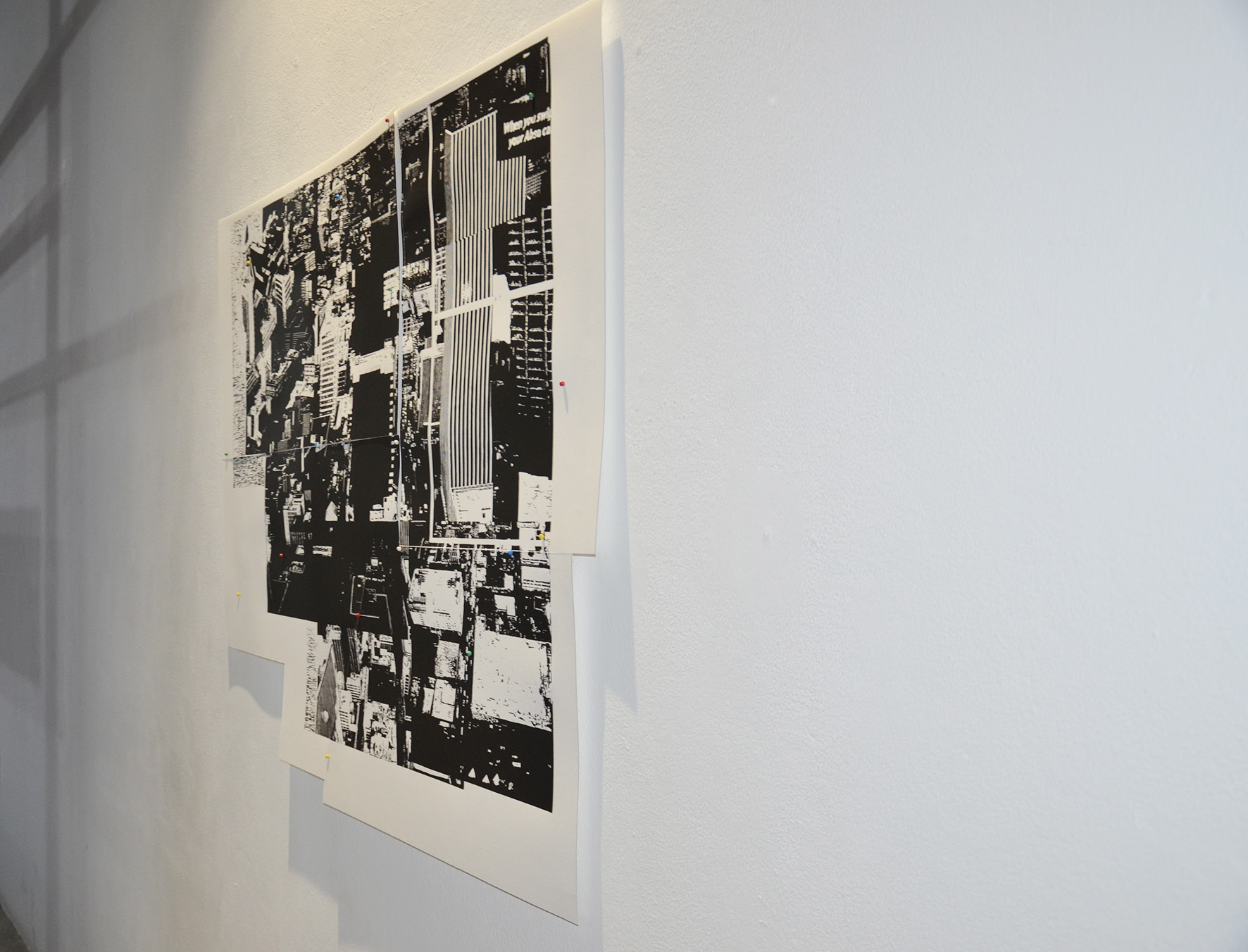

Framing- white- female- emerging artist- my eyes- camera- images- physical collage- print- in my mind- digital- photoshop- film strips- chance- abstract- representational- titles- When You Swipe Your ABSA Card- overlapping- labour- different people’s labours- my labour- making sense of my surroundings. Sarah-Jayde Hunkin locates herself within the city. Her processed-based work is centred around the transference of images and collaging experience. Frustrated with the lack of female representation in linocut printmaking, Sarah-Jayde is interested in the perception of ‘aggressive’ mark-making. Her print combines techniques of visualising negative space as well as delicate and fine marks.

Kira De Cavalho‘s MAPPING SPACES articulates locations topographically. The combination of paint and chalk is used to mark a fabric surface. The suspended map spans. “between my childhood homes (Mulbarton, Rosettenville and Kensington). The graphic threaded floor plans overlay the map and symbolise personal dynamics within my living spaces. These dynamics and associated traumas are expressed through different coloured cotton thread and linear layout.”

Nishay Phenkoo‘s Matrimonium study after The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even engages with its implicit Duchampian reference and the union of personified forms. “The deep enveloping gaze of the easels consumed within each other offers insight to the complexities of the marriage, its off-white veil of dust elegantly poised atop the head of its recipient awaiting a hopeful life of bliss and happiness.” Hymn Die Irae by Polish composer Zbigniew Preisner reverberates through the space while, “The recipients deeply intoxicated by the other lost in a subliminal bondage under the warm pink light imbued with parallelisms to the hand of god.”

This year’s winner, Kundai Moyo, explores issues of consent within the photographic practice. “I became curious about scale and the illusion of intimacy and that often lends itself to things that are small enough to fit in the palm of our hands, the psychological effects of this attachment and whether or not presenting something on such a small scale diminishes some of the problematic notions attached to it.” Her sculptural works entitled, Photo Albums: Vol. I & II are two tiny velvet-covered hand-bound books each containing a photographic series captured in Mozambique last year. Many of the images feature the human subject going about the doldrums of daily life. After producing the series, Kundai contemplated the moral dilemma of exploiting the image of strangers and the inequal power dynamic inherent in photography. She decided to, “construct a mechanism that would allow for viewers to peer into the lives of these strangers in a way that did not leave them exposed to the essentialist scrutiny that often comes with the unanimous viewing by a large audience.” Her photo albums attempt to create a tender moment of intimacy in the interactive piece.

The exhibition runs until the 7th of August.