Hearing about young, womxn-only collectives in Johannesburg is always a moment of excitement and encouragement for me. It speaks to the importance of collaborative work as well as the necessity for womxn to provide creative and emotional support to one another when learning to navigate art spaces in the city. Pussy On A Plinth (POP) is one such collective. The collective includes the artists Yolanda Mtombeni, Boipelo Khunou, Lebogang “Mogul” Mabusela, Allyssa Herman, Cheriese Maharaj, Lara Bekker, Zinhle E. Gule, Penny Muduvhadzi, Nthabeleng Masudubele, Didi Allie and Janine Bezuidenhout.

When asked about where the name for the collective came from, they shared that it emerged out of conversations about an image from a nude shoot that involved two of the members. “In one of these images, one of them was seated on a plinth. That is when we began discussions around what that image could possibly mean.” Wanting to unpack this further, I asked about what kind of ideological weight they are hoping their name will have, particularly when combined with their creative practice.

“The name attempts to disrupt the patriarchal structures both in society and the white cube gallery spaces. Putting a pussy on a plinth speaks of uplifting, bringing attention to, as well as monumentalizing the work of womxn artists. ‘Pussy’ in this instance, is used as a reclamation of power by attempting to normalize the use and essence of the word as a term that is not derogatory or belittling.”

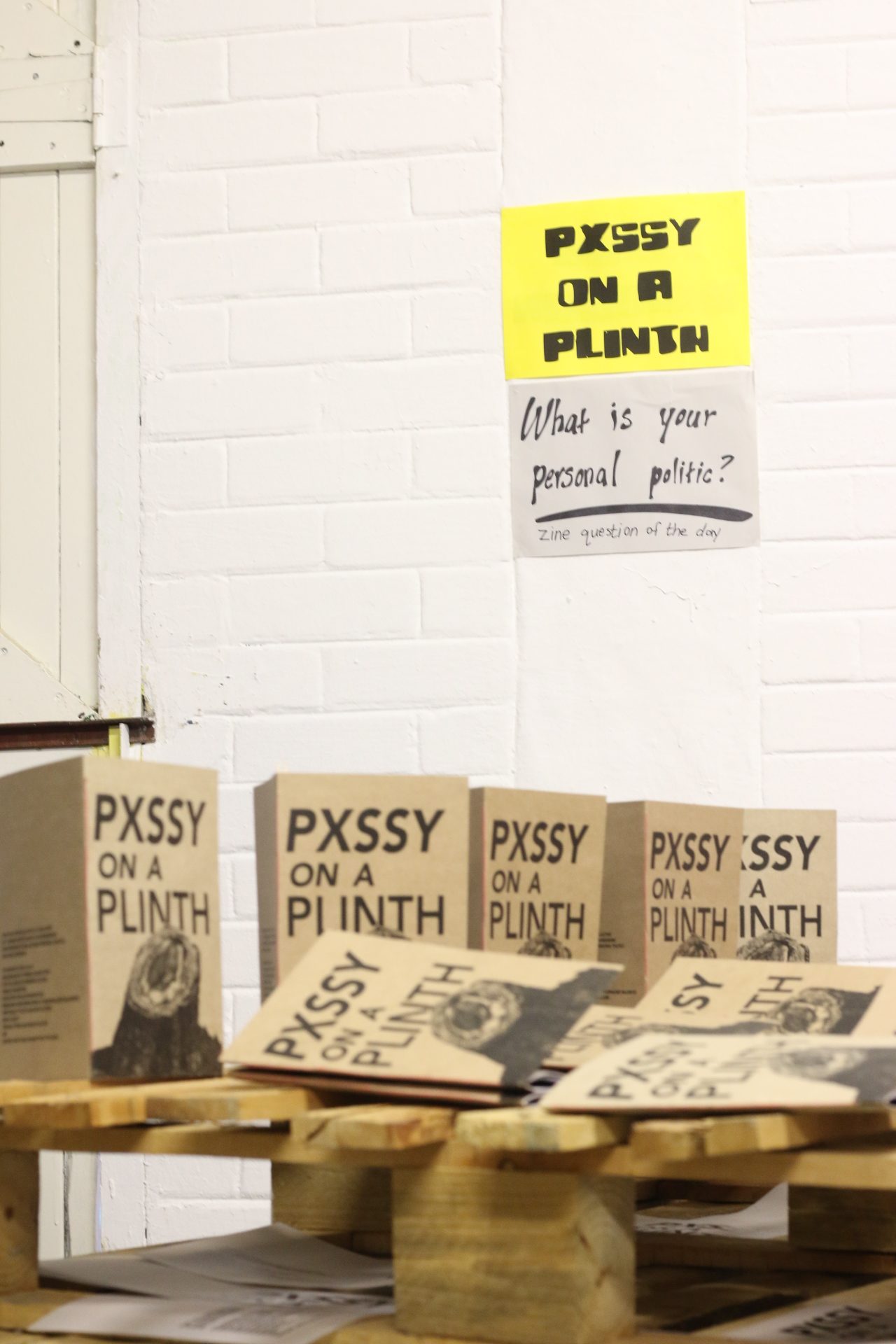

Since the inception of POP their work has manifest in the form of paper-based prints and zines. These are often guided by reflections on their experiences and thoughts as womxn. “Our work is interrogative, illustrative, engaging for the public and thought provoking,” they express.

The most recent display of their work was at the Lephephe print gathering towards the end of 2017, which was hosted and organized by Keleketla Library! in collaboration with the collective Title in Transgression. For this they created an image-focused zine to introduce POP and its members. In addition to this they hosted a zine workshop that zoomed in on the question ‘What is your personal politics?’ Reflecting on this, they shared that “the experience was inspiring and affirming; [it allowed us to] communicate our processes, thoughts as well as our goals with the public and other artists in the space as a collective.

The work of the collective and of each member ties into the ideas shared by the 70s feminist slogan ‘The personal is political’ which was adopted from Carol Hanisch’s essay by the same name. Individually, under this larger umbrella, they each have specific areas of focus, which sometimes overlap. These include patriarchal culture, post-colonial or gendered culture; the gaze, human consumption, black womxnhood and its experiences; mental health and associated topics; as well as the effects of post-colonial, patriarchal and gendered cultures. When listing these themes, it is quite easy to see how their collective has become an extension of their individual thematic foci.

When asked about what they have in the works for 2018, they shared that, “We are working on hosting more zine jams at various spots in Johannesburg where people can engage and contribute to the zine archive that has started building up. There is also a plan to have a womxn takeover at the DGI studio as a type of physical alteration of the male-dominated space. The result of this will be a print show which we have been organizing for a while now. The prints we will be producing will mostly consist of relief prints, ‘relief’ being in the form of printmaking, but also as a literal form of relief for us as womxn, as a collective and as individuals.”

POP hopes to continue to grow as a collective by getting involved in work and art spaces beyond paper-based prints and zines. To keep up with their growth and the possibility of new artistic directions, check them out on Instagram.