Walking into the side entrance of The Point of Order (TPO) I am greeted by varying colours of fabric cutoffs stitched together. Camouflaged between these, are the words ‘DREAMS THAT MY BOdY’ – an impactful introduction to the Masters exhibition by Chloë Hugo-Hamman titled A Womxn’s Dis-ease.

Walking between her works that are installed on either side of the exhibition space, I move excitedly to where she has set up camp on the other end of TPO. Sitting on a beanbag, surrounded by textiles of all colours and textures, Chloë greets me, a small stitching project in hand. “That looks like so much fun,” I comment. “Yes. It’s like a kind of meditation,” she replies. This opening fittingly welcomes my first question about fabric as her medium of choice.

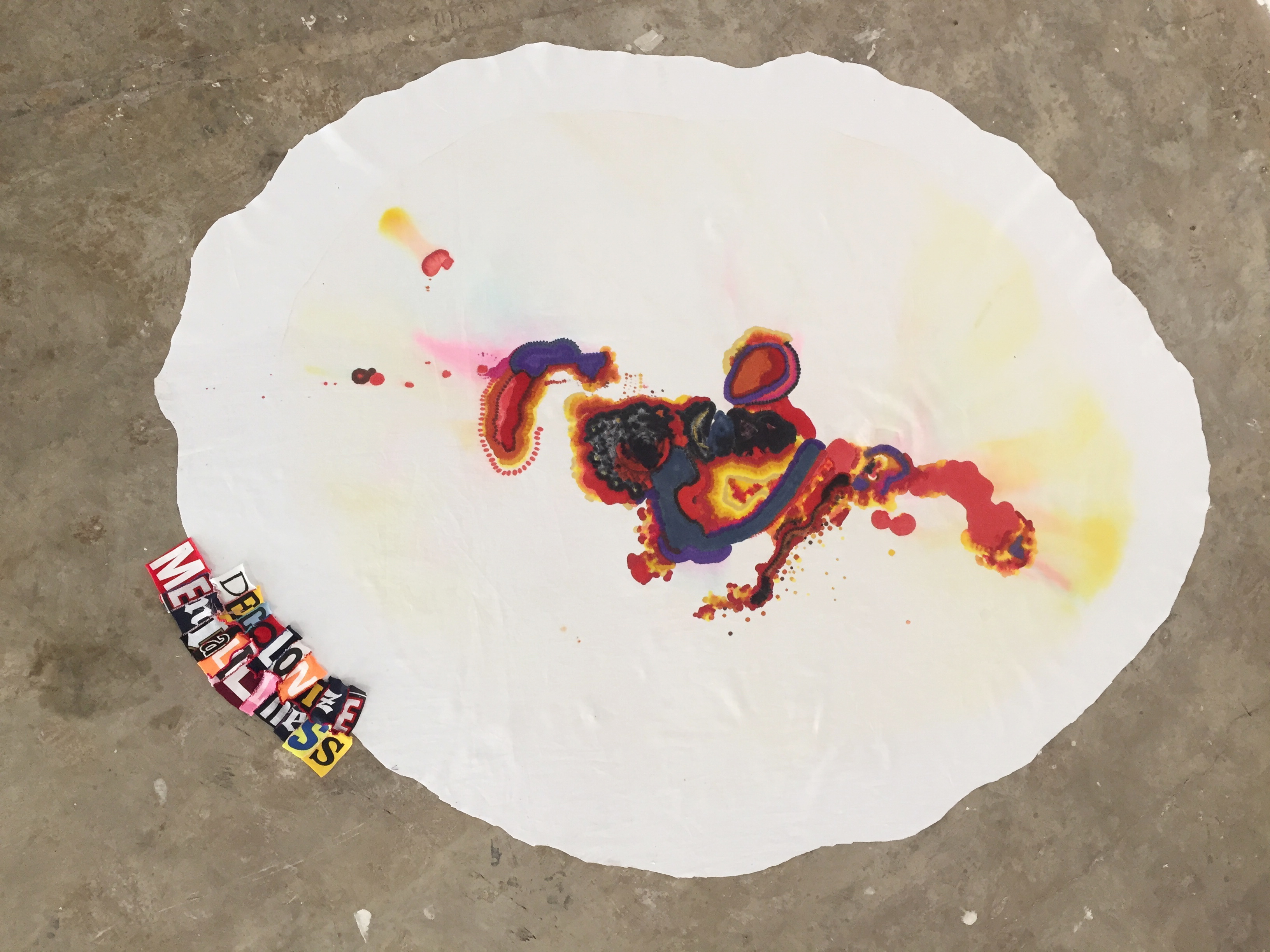

“I am very interested in textile. I love colour and texture,” Chloë explains. Soft, cosy fabrics appeal to Chloë’s eye, with these present throughout all the work that make up the show. Her specific hand stitching technique allows for her to work with the irregularity of the fabric, creating volumes that play on the textures of the reused fabrics. Her stitching, when viewed closely, also resembles veins, making a connection to the importance of depathologising bodies and ways of navigating the world. Letters are cut out of old t-shirts, and these are used to make up the words accompanying the visual pleasure of shades of red, pink, purple, yellow and blue that have been threaded together. This brings to the fore the interrogation of language within this exhibition.

“I made the words first. I was thinking about which words I want[ed] to incorporate into this exhibition.” Once these were created, Chloë was able to decide which words would be placed together, forming juxtapositions and dynamisms, and asking viewers to think about the tension that these groupings of words hold.

‘cHrONic SUPPOrT CaRe’ is once such grouping. This speaks to the lack of support and care in the world for what it means to have a chronic illness, and the need for that care and support structure.

“Chronic means that you will have it all your life, and unless you can afford the care – and even if you can afford it – it’s not really available in the way you need it. What I mean is that even if you have the means to access medical care, that care is prescribed by a largely Western medical framework, which is very much about responding only to the display of specific symptoms. If you don’t display the symptom, you won’t get diagnosed. And then there is the whole thing of language, because if you can’t articulate what your experience is using specific words, then you also can’t get diagnosed. But a Western medical diagnosis is also generally lacking, in that it is very seldom holistic in its approach to understanding the physical and psychic body. Then, as a womxn, it impacts further because of the patriarchal structure of [Western] medicine. A lot of the time you are dealing with doctors who are men, and their experience of the world is different to yours as a womxn. Their experience of violence and pain (and of how these can be projected and/or enacted onto a womxn’s body) is different, and often, as a womxn, you aren’t really heard or taken seriously. Your agency is compromised or negated. I am not implying that men do not experience mental illness or systemic violence, nor am I implying a stable categorisation or binary of gender as man and woman. Rather, I am pointing to the violence and therefore the pain implicit in a womxn’s patriarchal gendering. Which is also why I, like many other feminists, choose the convention of writing womxn with an ‘x’ as a strategy of disentangling ‘woman’ or ‘women’ from the subject-position of ‘man’ or ‘men’, and to consciously destabilise all rigid, violent and exclusionary gender categoristions.”

Following this train of thought is the idea of establishing alternative communities of care or “new forms of sociality”, a point Chloë takes from Ann Cvetkovich (2012), who is a seminal referent in her Masters. This asks the question, how can we create spaces and methods of care that are genuine, and provide a sense of safety, relief and understanding?

Continuing with the interrogation of language and the Western patriarchal biomedical framework for wellness and disease, is the work, ‘Sponsored by’. Taken from old t-shirts produced for corporate funded charitable activities, clusters of the words ‘sponsorship’ and ‘sponsored by’ are stitched together. In our discussion, Chloë comments on how most of these t-shirts were pointing to sponsorship for events related to breast cancer, with pale pink being the colour that is used to visually represent this. She points out the irony of these t-shirts, as the companies that sponsor these events sometimes have products or engage in practices that are carcinogenic. “And that was interesting for me in how it brings together a lot of my interests: big pharma, Western medical-industrial complex, symptom, labels, gender and feminism. Breast cancer is symptomatic for womxn, but it’s also so symptomatic of this capitalist system we live in. And also the fact that these t-shirts just have to be this baby pink! …it’s a kind of pink-washing!”

As briefly mentioned earlier, deconstructing processes of labelling in the way in which language is embedded within patriarchal structures of power presents strongly in the show. In the exhibition’s title the word ‘disease’ is re-framed as ‘dis-ease’. This is an empowering reworking of the English language, and draws attention away from the idea of the individual as the problem. It instead makes a larger commentary on the way in which the world operates. “It is less about ‘I am diseased’, more of ‘I have a dis-ease in the world’. The world that we live in is very fucked up, and you are meant to be or look or act a certain way; and if you aren’t that way you feel a dis-ease.” This ‘dis-ease’ can manifest in various ways, and Chloë’s focus is around mental illness.

A Womxn’s Dis-ease stitches fabric together to unpick neoliberal, white supremacist, imperial-capitalist, cis-heteropatriarchy.

To keep up with Chloë’s practice follow her on Instagram.