Durban is a city that is constantly evacuated, reconstituted, and returned to; kids throw their lives into bags and haul pieces of themselves back-and-forth while trying to find their bigger-picture footing. Despite is sleepy façade, things aren’t anchored in the same ways as other cityscapes; there’s an ephemeral and meteoric quality to the things that happen there… a strange landscape of abandon, interspersed with the flares of often-undocumented explosions. So I guess you can’t really tell unless you find yourself in it; something like that old beach-front swing-boat which goes nowhere to onlookers but from the seat, moves with such an incredible speed, it makes you think your head might explode. Sometimes the details get blurry, because everyone still carries traces of that delirious dizzy, but The Beard online magazine was definitely established somewhere towards the end of MySpace days; when gigs still had flyers and people had to phone each other to know what was happening. Justin ‘Sweat Face’ McGee had returned to Durban from Cape Town – where he had lined up an assistant-photographer job – with the intention of collecting the rest of his life to take with him. But things turned out differently when he snapped up a fairly random photography opportunity and then that portfolio was circulated, landing him further jobs. Based on the strength of his work, McGee rapidly escalated, within a couple of weeks, from ‘assistant-photographer’ to ‘photographer’ and so decided to stick around in Durban where he co-created The Beard with Dan Maré.

So, McGee found himself back in his home-town but not really knowing, or wanting to know, any of the people that were still around. Back then, digital photography was still on the upswing and he used to walk the city, armed with his first digital camera, which he ended up totally destroying trying to learn everything he could. The lens gave him the privilege of getting to look at the world and to document the visual landscape around him and so he would mission, sometimes from his place on the Esplanade to the beachfront and back, exploring and shooting as much as possible and embracing the format’s lack of turnaround time in order to develop his photographic eye. He tells me how he used to love getting in-between people, going unnoticed and capturing really dynamic, natural moments. Later on, when he became slightly infamous for proclaiming “I’ll make you famous” on the party scene, there was something of that same impulse- how he could put people at ease and get them to look really great through unselfconscious and un-posed images. McGee was always pushing himself and his craft and, wanting to stretch the possibilities of photography even further, started making digital collages of Durban, with each image working-in up to three or four hundred layers. This work inspired the format of The Beard, which subverted the linear point-and-click, scroll-down websites of the time by reading as one long, expressive collage, stretching horizontally across the screen and embedding posts within the visuals as a digital treasure-hunt. Like the scenes it documented and bridged, there was nothing sterile about it. Everything was frantic creation for the sake of creation, blazing from multiple spaces, in a city not totally bogged-down by the dynamics of hierarches of cool or profession or whatever. Because we’re going back here, the media landscape was massively different and The Beard was online before that kind of publishing was really prevalent. No one had cell phone cameras and selfies wasn’t a term yet. I guess this lent itself to the unrestrained and immodest energy of the time because no one really felt surveilled; it was all about the immediacy of the moment. There was also maybe something about Durban, where a strange sense of freedom developed because creativity wasn’t so economised and people often aimed to move out; nobody was worried about stepping on toes or being unpolished or judged- if you didn’t know what to do, you could just make shit up.

Being slightly adrift in a somewhat unrecognisable home-town, McGee used his camera to bite into some of the scenes and spaces that he wanted to be in, defining himself and his practice through the process. Cue the fashion kids who were studying from Brickfield Road at the time and who were also engaging in self-fdefinition; Ravi Govender, Jamal Nxedlana, Dino Perdica, and Harold Nxele. Feeling frustrated with what they saw as irrelevant information, being delivered in an uninspiring, traditional and restrictive environment, they began to rebel against the institution- radically redefining their own curriculum through an embodied practice. This began a powerful network of then informal collaboration and inspiration, where ideas and concepts were deciphered in accordance with their own realities and the ways that they had begun to live their lives. Upset Fridays emerged as a way to politicise fashion, disturbing and disrupting the authoritative limitations of that space by dressing provocatively and wearing their own definitions of what fashion could be. They took the tools they were given and used these to subversively dismantle; taking a social-psychology perspective on fashion, they would aim to destabilise and create uncomfortability in order to evoke a response, extending and blurring the boundaries between fashion and art. They already had tons of paint to work with, because they had figured out where to get the best vintage stuff in Durban. Ravi and Jamal had already been stocking some spaces through a label called Washed Up Nicely and knew that you could get the best international stuff- Mikey Mouse sweaters, Nu Rave gear and Canadian and American brands- at The Workshop piles, and all the local stuff- Jonsson’s overalls, old Natal swim jackets, 5FM, Checkers and political party T-shirts – at the hospice shops and the Victoria Street Market piles. Their immersion within those spaces, where multiple influences were running through alternative economies, and the rebellious desire to create new realities coalesced in an aesthetic that embraced the cultural value of Durban and that took all of it in, looked at all the different people operating in those spaces- the Gogos doing the selling, the Pantsula dancers, the construction workers- and recognised all of their individual style languages as valuable and unique articulations. So that Durban fashion crew took street-style, as well as their own versions of anti-fashion and (un)Fashion, and merged these with high-fashion; picking up on international subcultures and then projecting these through their own South African lens. They had originally been inspired by OGs like Puma and George Nzimande (aka George Gambino) and concepts like busting the funk but began to feel like they were surpassing this through their highly conceptual approach and so, when they linked-up with McGee and the platform his camera offered, it was unhindered and explosive.

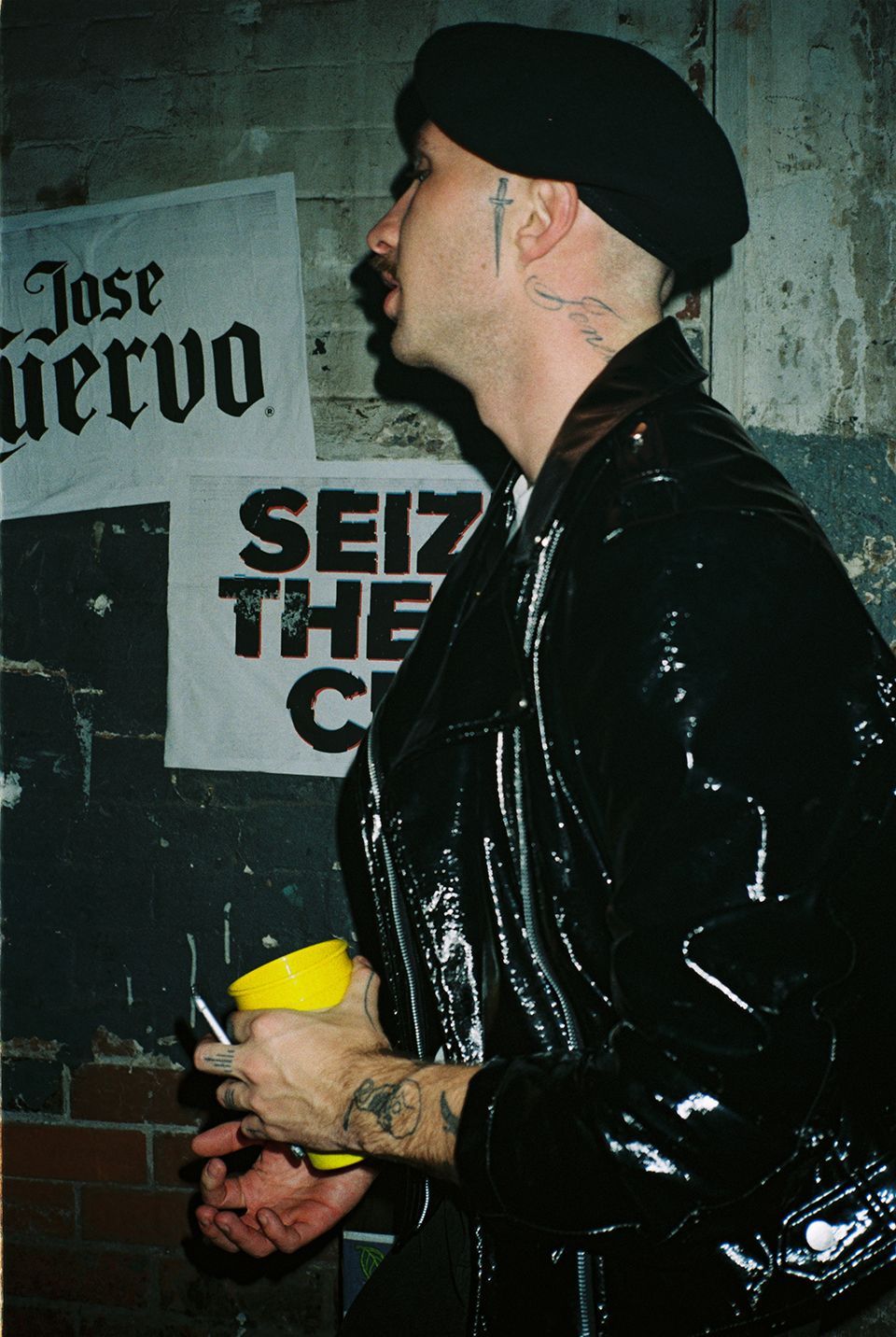

All of this was happening while the pub kids were refusing to let The Winston Pub die. Burn had moved from Umbilo Road and the space had emptied out, but Skollie Jols revived it and the band scene was thriving. Those were the days before the come-down, when all the boys had tons of hair, Blue was car-guarding, and Farrah could beat Meaty One at the drinking competitions. Sibling Rivalry were still jamming, Fruits and Veggies had its original line-up (Darren, Purity, Sweet Lu and Loopy), and most kids could bust-out a Big Idea track without thinking. The park had shut down but there was still the lot and the kids rocked it hard. Everyone made out with everyone else… especially the guys with each other. There was the creation of an alternative home for all of the misfits and reprobates, and because all of them were already in it so deep, they just kept on going until it blew-up as an untameable beast. If someone felt comfortable walking into that chaos and actually hanging out, they were welcomed. There was Bean Bag, Jamesons, The Bat Centre, and The Willowvale Hotel but because the city didn’t really offer the alternatives kids very much, everyone made their own spaces. It was all about uncensored affront and everyone was creating; the comic book kids were making comics, the punks were making music and the poets were busting out at the Life Check battles. McGee had starting going out with Illana Welman (aka Lani Spice) and JR (aka Dr Pachanga) was staying with him at the time. Graf artists like OPTONE, 2kil, and Fiyaone were kicking about and DJ Creepy Steve was just limbering up. Sweat Face started using his camera to infiltrate the pub space and everything just exploded in a really viral, organic way… different scenes were bridged and it created something really unique and dynamic, where everyone took bits-and-pieces from each other. All the kids spoke their own languages and code-switched until it was almost unrecognisable to outsiders. Everything was a collaged and remixed inside-joke, embedded with multiple meanings; get-in-the-car, zero-to-hero, trawling, going on tour, pop-art, free elephant rides, supporting life, pikey. Pastel Heart had just hit the scene and was bursting-at-the-seams with pure expression in his babbles and clicks- everyone loved him, even if they couldn’t understand him, because they were all on their own vernaculars.

Because the scene was so small, it operated as strange extended family; no one fitted in, but everyone was somehow outside, together. If immediate families were around, kids would often subvert these structures, heading to friends’ places in subdued attire only to switch-it-up and hit the night in camis and capes, strut in Mary Janes and sparkle-pants. The Beard documented some of this subculture and also offered a platform for the Sunday Workshop, where the fashion kids would take turns setting conceptual creative-briefs. They’d all get styled-up and head out to shoot or they’d invite friends over to Sweat’s spot and party and make DIY backgrounds and sets… just curating and shooting as much as possible in a totally unfiltered environment. The images and styles they created pre-empted a lot of today’s youth cultural crews, with the international being reflected through the local. Everything was reimagined; Versace prints, Balenciaga futurism, and Nu Rave were all mixed-in with visuals of the South African political, Vaalie vibes, Sangomas and Kondais… and it was all about Durban spaces. The Beard was online before anyone was really aware of the internet’s possibilities, so when Ravi, Jamal, Dino and Harald would hit fashion events in other cities, and hear people talking about the Durban scene through the images McGee had captured, it was one of the first times they realised the internet’s potential for creating connections beyond the IRL. Creativity was exponentially amplified because everyone one was pushing and feeding-off-of each other’s energy. Nothing was precious and ideas were fast; no one was saying lit… it was basically cult. That whole crazy-blur-of-a-moment set a precedent for who McGee would become as a photographer and incubated approaches and relationships that continue today through collectives like CUSS Group and Bubblegum Club. No one came out unscathed and some of the kids kind of lost it when they realised that the world isn’t made for such big living- I guess hostile hierarchies were easy to forget when everything around them was their own lavish creation. But the originality of those times is totally unshakeable and although most have scattered, they’re still out there, carving out strange spaces and definitely making a scene… stay weird kids, xo

The Mag

The Nights

The Fashion