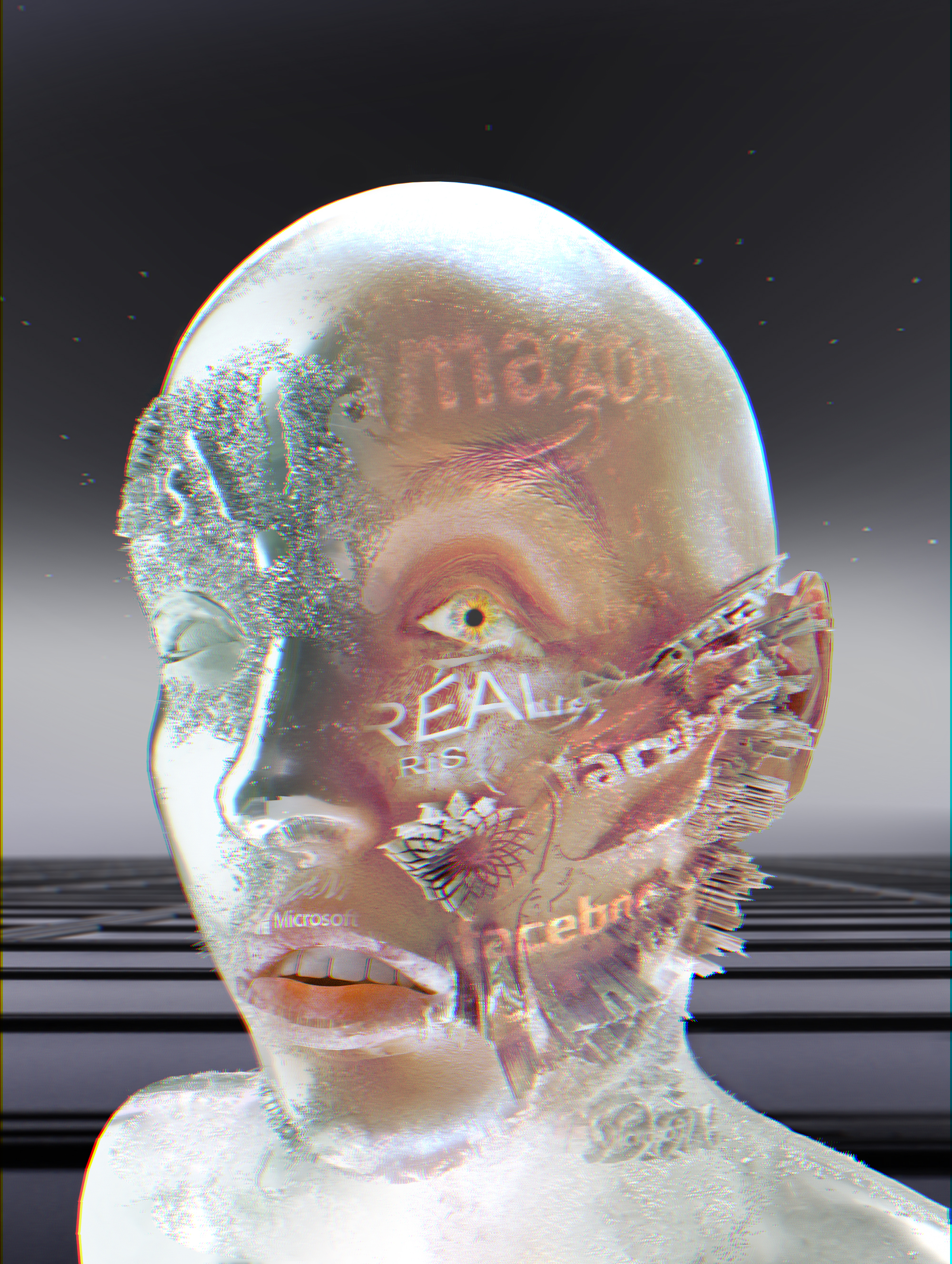

Brands, research institutes and related companies are mining our own species for data. The everyday human is consciously and unconsciously being used as an instrument in the branding and information machine, reproducing a “consensual hallucination” in which data may be visualised, heard and felt (Stone 1991: unknown page). Stone uses this term to refer to virtual reality, however it seems easily applicable to our current state of existence.

The kinds of brands we wear say something about who we are, making our purchases identity signifiers and constructors of specific kinds of bodies. The placement of brands on bodies by wearers becomes a source of information. They become social, cultural and economic indicators.

Combined with this, our behaviour, interactions, the content we produce, the calls we make and texts we send add to our position as data mines. The body and the mind continue to be framed as independent operators with aspects that can be isolated for closer inspection, in the name of better customer experience or getting to know what the consumer wants, often before we even know what we want.

Even the devices we use to engage with the virtual are produced by the interfaces and programs designed by brands, curating specific experiences and imagined futures. People often take these devices and applications and construct their own uses for them, sometimes redirecting their intended purpose, but always limited by the parameters set out in code and hardware.

Companies are using location data, watching where and how we conduct ourselves. Brands no longer need to interact with our physical presence to collect this information. The coded you is all that matters, and this is the data that is increasingly being mined by companies to predict trends and create campaigns. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal is a recent moment that highlights the reality of this, affecting 87 million users.

An image of you already exists through tags, internet searches, information uploaded on apps and GPS locations. Our digital footprints and the traces we leave in virtual space are being woven together by brands, resulting in a frightening, generic yet familiar reflection of ourselves being presented back to us. How is it that adverts that pop up online are able to be connected to the conversation I had with a friend over the phone? Is this coded, simulated version of me that is constructed through my digital footprint infiltrating my consciousness to tell future me what I should purchase and how I should interact?

The body and the mind create data, and the way in which this data is mined and the way in which this information is used is threatening the future of the biological human body. The boundaries between technology and nature continue to collapse, and the information from the body is being used to find ways to correct its imperfections and fragilities, removing its nature from its future. Info about the mind is preserved to keep some form of humanity, while trying to create artificial bodies that can house this information.

“The illusion will be so powerful you won’t be able to tell what’s real and what’s not” – Steve Williams

Stone (1991) mentioned that it is interesting that at a time when the last of the “real world” anthropological field sites are disappearing, a new kind of field opened up. That of the online field – a space where meeting face-to-face has mutated definitions of “meet” and “face” (1991: unknown page). She highlights how these spaces have sped up the collapsing of the boundaries between nature and technology, biology and the machine, the natural and the artificial, as explained by posthuman theorists. These spaces are part of new social forms which she describes as virtual systems (Stone 1991: unknown page).

Stone presents an example of the power of these coded spaces and the new forms of interaction they have engendered through the story of Julie. Julie was an older disabled woman at a online conference in New York in 1985 who operated her computer with a headstick. The personality she projected online was huge, creating computer-mediated connections with people online who viewed her as a friend to confide in about intimate information. Here, her disability was invisible and irrelevant. Years after the online conference participants found out that Julie did not exist. Turns out “she” was a middle aged male psychiatrist who had spent weeks creating a believable persona. Accidentally starting up a conversation with a woman who mistook him for a woman when logged on to the conference, he was entranced by the vulnerability, complexity and openness that these women expressed online. Once the real life truth behind Julie was exposed, the women who had confided in her expressed various levels of anger and hurt from this trickery. While this story comes across as a triggering and chaotic episode of MTV’s Catfish, it points to a dimension outside of the transformed nature of deceit, ethics and risk. This dimension is the beginning of an un-embodied existence.

Stone’s paper Will the real body please stand up (1991), among other discussions, highlights how the internet, virtual reality and machines have mutated concepts like distance, inside/outside, and even the physical body, emphasising how these concepts are increasingly taking on “new and frequently disturbing meanings”. The story reveals how the coded persona can take on a life of its own, creating new forms of interaction within this virtual dispensation. What is more striking is how this demonstrates how the discursive and visual dynamics of these digitally constructed spaces make grounding a person in a physical human body meaningless (Stone 1991). If interaction and relationships can form without the necessity of the human body, and the fact that all that we do and all that we are is treated as data, then the idea of existing without the biological human body does not seem like such a far-fetched idea.

A life produced. A life un-embodied.

“If anything can be ‘produced’ then it can no longer be accepted as a fact of nature” (Stone 1991: unknown page).

From the construction of personas and interactions mediated by computers to being viewed as data, all of this connects to the idea presented by transhumanists – the idea that the mind can exist and function properly independent of the human body (Bostrom 2003). Transhumanists cling dearly to this idea of substrate-independence. This arises from framing the mind as information that can be uploaded and transferred between hosts provided that they have the computational power to do this. This reference to “mental states [being able to] supervene on any of a broad class of physical substrates” has been adopted by biomedical and technological researchers and developers. Overtime there have been companies and institutes gearing towards the creation of computational structures and processes for artificial “bodies” that will be able to host the conscious experiences of the mind.

The context within which these developments take place are that of environmental destruction, disease, wanting to live longer and the desire to see how far we can push science and technology.

Reflections on the ways in which we have accelerated negative environmental scenarios, combined with desires to live longer and eliminate diseases and genetic “malfunctions”, has led to biotechnologists, geneticists, biochemists and businessmen using these visions of a dystopian future to brand risky enhancements, artificial bodies, and their ideas for a new phase in humanity as beneficial, necessary and inevitable. Geneticist and businessman Craig Venter is well-known for mapping the first human genome in 2000, for his synthetic genome experiments as well as for emphasising how we must manipulate our genes in order to survive. He has recently taken it upon himself to decode death, believing that he is able to discover diseases dormant in seemingly healthy individuals. People can pay for these genetic tests at Human Longevity, where Venter is the executive chairman and head of scientific strategy. This health firm aims to stay ahead of illness and aging, and is described by Venter as a company that is a “good detective…making discoveries, not diagnoses”. Again we see how data collection is conveniently marketed as a necessary preemptive measure, but with genetic manipulation the end goal – reconstructing the very blueprint of the biological human body.

Venter is not the only one looking to edit and rewrite the human genome, with researchers discovering CRISPR Cas9, a programmable modular complex that can be directed to target and cut specified DNA sequences, allowing for the possibility of repurposing different kinds of cells, editing the genome.

The above are painted as positive mutations, either masking the companies backing this research, or presenting the companies as good fairies. These enhancements and adjustments are branded in the same way one would brand products, with an emphasis on how they can benefit people now and how they should be viewed as investments for the future.

Taking this a step further, there have been predictions that the earth will be uninhabitable for humans and most other life forms in their current state by the year 2045. David Russel Schilling wrote in a 2016 article that “The only hope for humans to survive is to create robots that don’t need oxygen or fresh water to survive. Over the next three decades, technology will likely allow robots and the human mind to merge”. With this prediction, groups of humans who are able to afford these procedures will live in a post human era.

The 2045 Strategic Social Initiative has put together a manifesto and videos, highlighting the need for these artificial bodies and the transferring of human consciousness, framing this as an improvement on human life.

“People will make independent decisions about the extension of their lives and the possibilities for personal development in a new body after the resources of the biological body have been exhausted…Using a neural-interface humans will be able to operate several bodies of various forms and sizes remotely”

This quote demonstrates a kind of cybernetic immortality, which is visualised and being funded by businessmen such as Russia’s Dmitry Itskov. Here we see agency being used as a branding tool, pointing to the possibility of curating ones own experiences through these “bodies”. We may soon have to imagine a life where we choose the service provider of our artificial tool to experience the world, whether this be a computer, a body that attempts to mimic the human body as we know it today or some other kind of extended, produced body. It could be as simple as a paying for a cellphone contract today.

It is the year 2060. The chronological destination for the new humanity. We have managed to figure out a way to unfreeze and bring back to life those who chose cryogenic freezing. Research teams have developed multiple models that can be used as portable and moveable bodies for those who wish to experience the world through those of their ancestors. AI creatures are our friends and everything is downloadable, uploadable and transferrable, including our very personas. The use of the word human now references the second last being on the well-known evolutionary diagram. Looking for a body is like creating a Sim, with less emphasis on hair, eyes, or skin but on computational ability, processing power and minimal disruptions.

The dystopian future is being used as a branding tool, justifying the use of people today and possible artificial bodies of the future as data mines. These artificial bodies will still be operated through the parameters set out by the companies that design and develop them, continuing the thread that we can be used as data mines.

Considering that this research is being conducted within a specific social, cultural and geopolitical moment, these technologies will carry traces of how we frame ideas related to betterment, enhancement and enjoyable ways to live in the world established today. More specifically, they will preserve the agendas of the companies and research institutes developing these technologies today, and the lineage they will create in this future.

Regardless of how transhumanists try to frame our future selves, it cannot escape from the fact that researchers funded by companies are the ones who will propel us into this human-engineered phase of evolution. When reading between the lines, this is a kind of escapism. An escape from disease, age, death, politics and other fragilities that come with the current human existence. It is about making these constructed fantasies more than an experience with an Oculus, but one in which we live. A hyperreal, consensual hallucination that is built on data to be collated and uploaded for a transhuman future.

References

Bostrom, N. (2003). “Are you living in a computer simulation?”

“Cybernetic Immortality”: How to live forever as a robot

Debord, G. (1967). The Society of the Spectacle

Facebook scandal hit ’87 million users’

Genome Pioneer Craig Venter is trying to decode death

Stone, A. R. (1991), “Will the Real Body Please Stand Up?” in Cyberspace: First Steps. (ed.) Benedikt, M.

The Way to Survive in 2045 May Be In Artificial Bodies

What if we could rewrite the human genome?

With Privacy Changes, Instagram Upsets Influencer Economy

Credits

Concept & Research Paper: Christa Dee

Photography: Jamal Nxedlana & Lex Trickett

Creative Direction: Jamal Nxedlana

MUA: Orli Oh

3D rendering: Lex Trickett

Product Design: Chloe Hugo Hamman

Research Assistant: Marcia Elizabeth