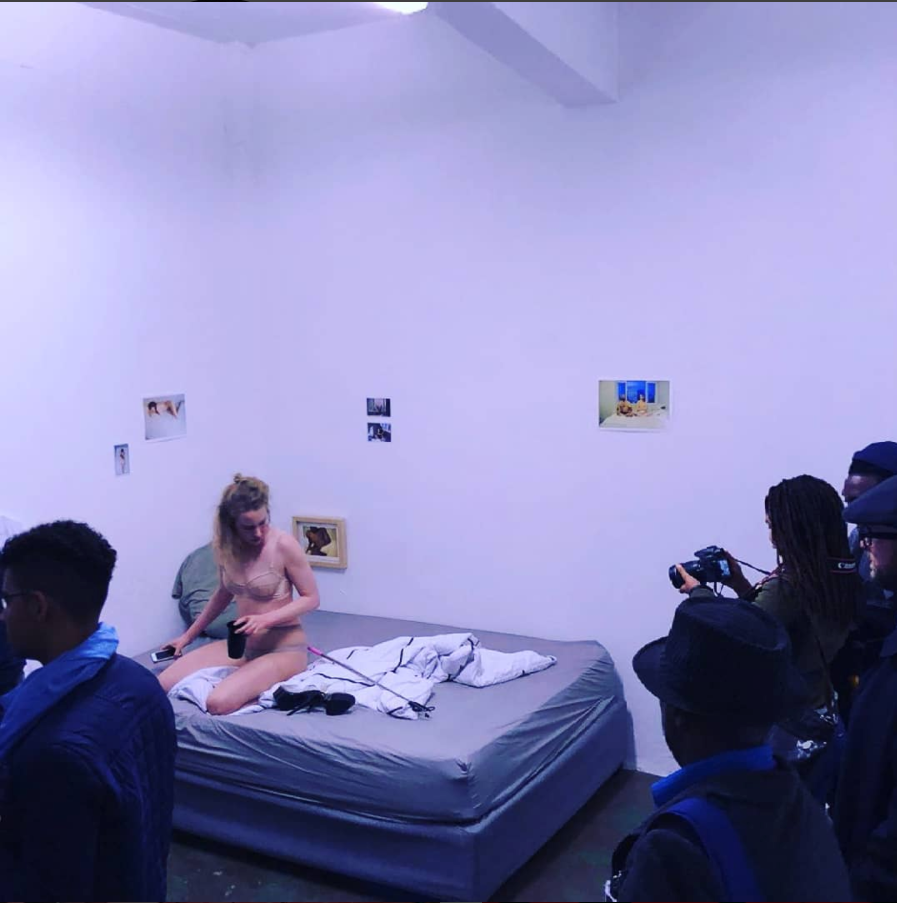

Nico Athene, artist-cum-former-stripper-cum-filmmaker is reminding us that the glass ceiling is far from broken. She represents a new generation of ‘disrupter’ – as a queer figure, a female figure, a sexed figure, a bodied figure – notions of space, form, gender, sex, objecthood and the abject are foregrounded. The bed, a space of intimacy, rest, solitude – becomes Get In My Bed – and Athene ‘publics’ the private. The contemporary female artist always endeavours, always competes. So, we allow ourselves to relish in our discomfort, as we snuggle into the duvet. I was lucky enough to ask Athene a few questions regarding her practice, and how the binaries of consent/transact/covert/overt begin to muddle in this work.

It seems a large part of your work engages with the notion of transactional and consensual sex. In many ways conflating the world of art with the sex industry disrupts the boundaries of both and makes us consider as the viewer what is transactional and what is consensual. Inviting fellow artists into your bed is an interesting disruption of this. Can you maybe elaborate on your decision to create this collision?

Sex work is often very consciously performative, and in this way, it is an aesthetic practice. If we don’t recognise it as such it’s because of economic and patriarchal class norms working as a form of censorship, deciding what is or isn’t ‘aesthetic’ and therefore legitimate practice/bodies/work in contrast to the taboo/illegitimate. These norms also enforce economies of access.

With regards to the ‘transactional’ vs. ‘consensual’ the idea that these two things are necessarily separate is a myth that works to police female and queer bodies and their labour/worth and draws on the previous point to suggest that those who do it are not ’empowered’ or ‘conscious’.

As femmes we all do sex work every day in forms that are less obvious, and often less conscious, to those who do it for a living. It is my experience that in inhabiting this body I am required to do gendered labour and performance in the service of male egos (ie. sex work) just to be treated ‘fairly’ or get anything done, across all the industries I have worked in. The irony of course is, that despite my performance or under performance I will STILL hit a glass ceiling. Keeping everyday sex work invisible serves to maintain this status quo, keeps us performing for free in service of the hetero-patriarchy. Transacting for sex work challenges those who feel entitled to our bodies and sexuality, especially to those who think they should be getting this labour for free. Making it visible means we can know the extent of our embodied and symbolic work and charge for it properly.

The way we consider and delineate publics and privates is highly moralised, along very normative gendered notions that work to police bodily autonomy, ownership and pleasure, especially if it is femme/queer. The body of a Sex Worker inherently disrupts this. It is a punctum to the bigger debate, a debate that includes the conditions through which we consider art/artwork/art audience vs everyone else.

Of course the residency in my bed was also a symbolic transaction – of my intimacy/spectacle/proximity/idea in exchange for the cultural capital of the artists present. It was a way of drawing attention to the aesthetic potential of the embodied labour that is put on me by society, that I hyperbolise, and as an early intervention, a way of canonising myself out of the taboo and into the role of ‘artist’. A reversal in agency of the ‘artist-muse’ dialectic.

Most recently you showed at Kalashnikovv. How was this experience different from when the residency was at home in Cape Town, and how does the gallery space differ in terms of how this work was read?

It was of course very different for many reasons, each space has its own set of established semiotics to do with transactionality and the body, the artist and art object, so it was an important evolution of the public/private queering. What made the greatest impact on me were the oversights related to being in the gallery space – as a body, holding this position and occupying this space – I became aware of cracks which have a lot to do with the intersections of how these spaces are run and for whom and whose comfort–and whose embodied and psychological safety and enjoyment. The fact that the bathrooms were in another building with no light or security or soap, for example. Or that some people felt they could just walk into the space and photograph me without my consent. I was also violently sexually harassed on leaving the space by someone who had been at the installation. These were not things I had necessarily considered either, even being in this body, before being in the space, so it was a learning curve.

Have you had hostile reactions to your work?

I’m not sure what that means. I have had threatening engagements around it. Like the harassment outside the gallery. And I have had male artists take advantage of it or try moralise it under the guise of care. One of them was in my bed as part of the residency. He is very well known and makes a lot of money off his work, photographing strangers without their consent – strangers who will never see the money that he makes off their images. I’m not sure if this is wrong, just worth noting. The agreement for him spending time in my bed and photographing me was that I would own the photographs. I was after all the instigator, conceptualiser and director of the ‘work’. He said up front that he was interested in the project because he was interested in photographing me in this role, and that he wanted to fuck me. I said he could do the former, but that I would not promise the latter, just that he could spend a night in my bed and we’d see what happened. I didn’t fuck him, although he tried the next morning while I was half asleep – its own trauma of course – and then persisted during breakfast when I had to also listen to him go on and on about how my project would be stronger if I had sex with all the participants and that he didn’t get the problem because it was ‘just a fuck’. In the end he sent me a single photograph, and when I asked who would sign it, he said we were no longer going with the idea that I was the artist.

He didn’t respond when I emailed him to clarify the agreement, although I did hear through the grapevine that he was still bemoaning the fact that I didn’t fuck him. I’m not sure if it was a hostile reaction, more an expansion or illumination of the work and the dynamics and positions that it challenges. I am interested in how typical art models and the laws that support them view and maintain certain subjectivities and give or take away agency by determining how and what we view as the ‘art object’ vs the ‘body of the artist’, or just ‘the artist’. And of course, this reflects entirely on ownership and access and economy. Another, very famous TED talker and MOMA exhibitor who befriended me in the USA, kept suggesting I try make art from my ‘centre’ rather than my ‘edges’. This of course after he used me as an ear to all his kinky proclivities. When I asked if he’d be a referee for an application for an award of which he was an alumnus, he refused because he thought the project, which was about reconciliation through the body, was from my ‘edges’, and suggested I make work about my family instead.

Instagram seems to be a major platform on which you reconsider body politics, and the female form. How important do you think platforms like this are for the contemporary women artist? Especially considering it has become almost a site of activism – I am thinking of the Free the Nipple campaign for example.

I don’t aim to use Instagram as activism, although it allows a certain kind of activism as a platform outside of the institution to show work and generate publics. Having not gone to art school, this function of Instagram is particularly useful to me. Of course, working outside the institution is disruptive of a certain power, and Instagram’s censorship policies work to enforce other kinds of power.

On the topic of activism, do you consider yourself an activist?

My primary interest is in what it means to engage in aesthetic practice and the experience of living through/as/with this body. I am interested in how the body and embodied labour IS an aesthetic in its own right, and the terms through which we do and don’t recognise it as such, and what they say about ourselves and society. These terms/experiences are obviously very political, as much as they are intensely personal.

There has been quite a history of performance artists occupying the gallery space – last year Dawn Kasper took up residency in the Giardini at the Venice Biennale for 6 months, famously, Maria Abromovich spent hours in MOMA for her work The Artist is Present, Tilda Swinton slept in a glass box in MOMA. How do you think your work is different or similar to theirs? Why do you think this is a predominantly female artist phenomenon? Do you see your work as a particularly ‘feminist’ activation?

I don’t know much about art, I didn’t study it, is my brief and sassy answer. No but really, I’m not sure if it is useful for me to compare my work to other performance artists just because they also use performance or their body. I’m not sure if I think of myself as a performance artist anyway, more an installation artist. I think that there is something to say, however, for the fact that we who do this are trying to escape the violence of language, including for example, the idea that there is a distinct ‘female’ locale. So queers and femmes are probably more driven to forms like this as opposed to cishet males – perhaps because of the language of inherent binaries and the dissociation from the reality of what it means to exist as a body. Explaining your work and experience through language (like I am doing here) perpetuates this violence and detracts from the protest of the action or the discomfort of the situation. It suggests that such things can be organised into accepted and knowable categories where there are subjects and objects, i.e. on patriarchal terms. Or that bodies and their experiences can be ‘known’ through abstractions and ‘reason’ and according to the linearities of language. It is doing the work ‘for’ people who are trying to oppress you by requiring that you explain yourself/and your body, to them, in ways that make them comfortable. Of course, it is a catch 22 as we’ve developed a world where we communicate primarily through language (esp. since the internet), but still it is working on their terms.

What is the importance of your work in a South African context?

I don’t know, I just know that it is important to me, in this body, trying to survive by making sense of my experience outside of accepted or known or comfortable categories, and to make the discomfort of the known ones visible.

And finally, where is your artistic practice leading you in the next few months?

I am interested in the abject – the stuff outside of categories or language or western notions of linear logic. It is part of my fascination with the reality of what it means to be a body. I think that’s why female bodies threaten male societies – we shed more visibly, we bleed, we birth. And yet all these strangely canonised notions of ‘sexuality’ are built on the abject – hair, nails, eye lashes – things we find disgusting when they are removed from what we perceive as ‘us’ or the object of desire. Yet we are creatures of abject – taking in and expelling food and air and shit and sexual fluids – we are a constant negotiation of the outside and inside worlds. We are permeable inspite of our discomfort with the idea that we are not concrete. So, I am working on this, and showing it, in various contexts. I have made a series of ‘paintings’ which try to disrupt this artistic language too. The majority of western art is notoriously disembodied and cerebral in its attempt to concretise and solidify and make value through permanence – through embodying something outside the realities of our mortality. My paintings are a performance in their own right I guess. I like a painting you can suck and set on fire. I will be showing them and doing a performance as part of group show at Gallery One 11 opening next first Thursday, 3rd of May. Some more exciting things in the near future here and overseas. Not quite confirmed so I’ll keep them quiet for now. You can find out more through my site and Instagram – will try keep them updated!

Nico is a body of colliding personas and intimate intricacies: of political and personal, immediate and distant, academic and under-qualified. Born and raised in Cape Town, South Africa, she has two degrees under her formal identity, neither directly related to art. She worked for a number of years in the creative film industry before giving up her ‘real name’ to become a stripper in a Cape Town club. She blames patriarchy and glass ceilings, ‘I figured that if I was going to be sucking cock for cash, I may as well be doing it for proper pay.’ Actually, it’s because she always wanted to be a dancer. It was here that she was born – a stripper/whore whose only mandate is to use artists and their institutions to up her cultural capital: a hyperbolised comment on demonised female stereotypes, sexuality and transactionality that constantly flits between the surreal and mundane.