This past Saturday, the Poetry Readings and Conversation brought together Gabrielle Goliath and Maneo Mohale in an event organised by the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. Founded in 1966 during a time of unthinkable violence and segregation, seldom has the institution presented us with such profoundly embodied explorations of Black desire, sensuality, and queerness in art. The happening was thanks in part to a collaboration with the Centre for the Study of Race, Gender & Class at the University of Johannesburg and its Global Blackness Summer School, whose theme this year is: For Wholeness. Black Being Well.

Selecting Maneo Mohale as the function’s facilitator was fitting. Not only did the poet and feminist writer have unstoppable chemistry with the guest of honour, but they were also incredibly qualified to take on such delicate subject matter. Mohale has contributed to various publications and served as a contributing editor at i-D Magazine. Their debut poetry collection, Everything is a Deathly Flower (2019), was shortlisted for the Ingrid Jonker Poetry Prize and long-listed twice for the Sol Plaatje European Union Poetry Anthology Award.

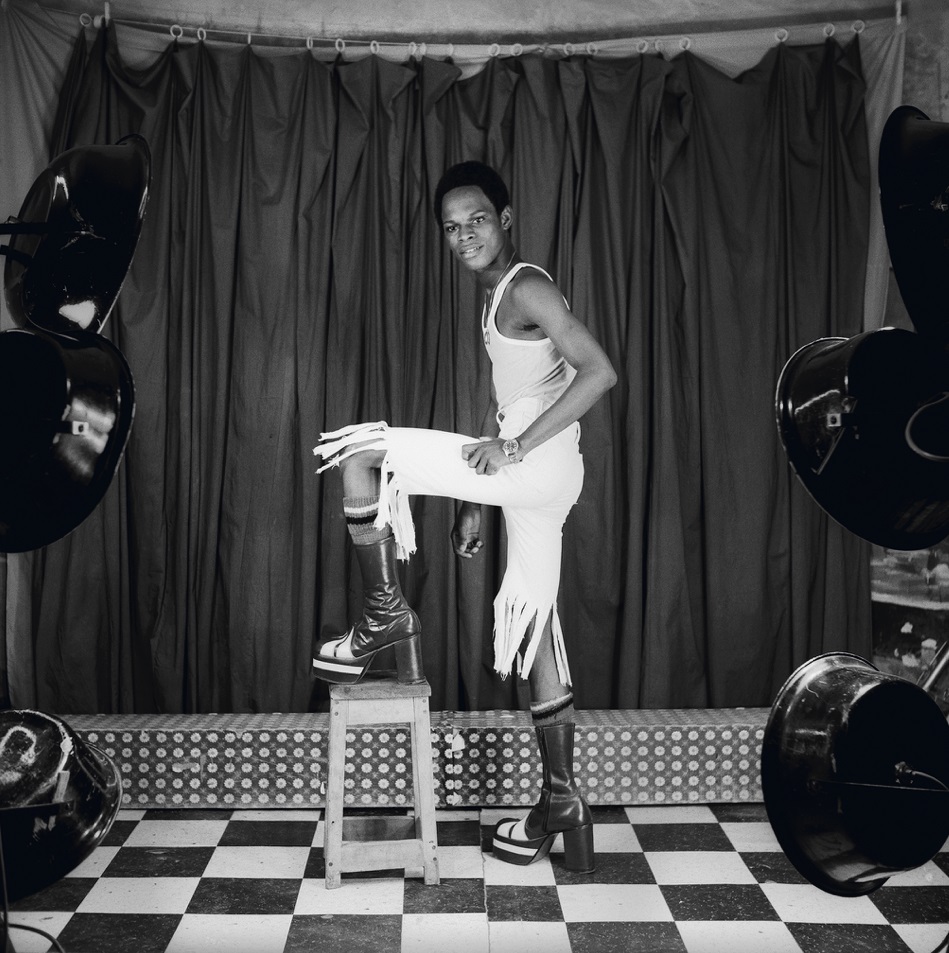

The recipient of the 2019 Standard Bank Young Artist Award, Gabrielle Goliath’s work is featured in numerous public and private collections globally including Constellas Zurich, Tate Modern, and Iziko South African National Gallery. Her new body of work Beloved at Goodman Gallery, features drawings and prints. The exhibition, running from October 28 to November 24, 2023, features representations of radical Femme figures like Gabeba Baderoon, Caster Semenya, Sylvia Wynter, Yoko Ono, Sade, and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. While primarily recognised for her sound and performance art, the day was all about Goliath’s autographic practice.

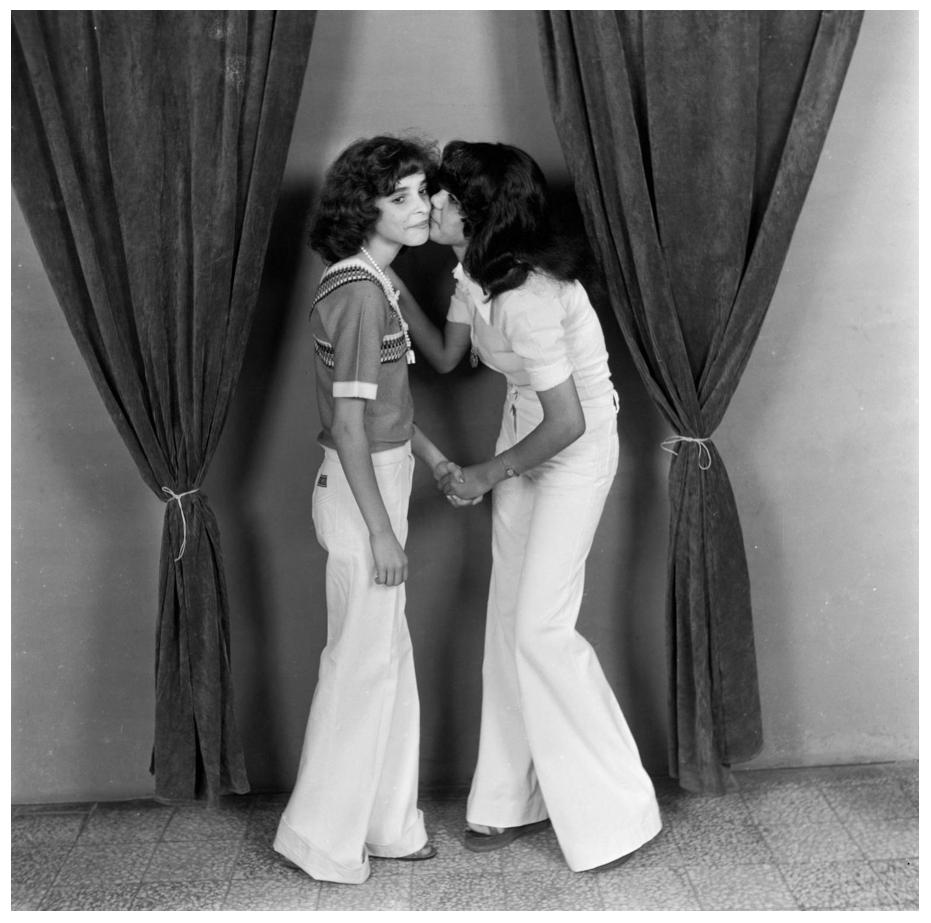

Mohale began by inviting the audience to take three grounding breaths. They followed by sharing a poem, The Autobiography of Spring by queer Palestinian poet George Abraham, proceeding thereafter to introduce Goliath’s Beloved. Peering out the coffee table in front of the speakers, one could see Toni Morrison’s own Beloved (1970). This setting and sequence of events set a very specific tone for the day. From the get-go, it was clear that Goliath and Mohale were engaging at the intersection of Blackness, well-being, and creativity, with a soft emphasis on themes of sensuality, and queerness.

The way they spoke to each other was gentle and generous. When asked about her practice, Goliath replied, “I want to first speak about this notion of mark-making as a means of being close…” Echoing the mood in the room, Mohale praised this tactile, material, and more physically engaged process. Goliath continued, “… that really refuses the sort of sanctioned genius of the male artist, who works from a removed distance. And I refuse that. The physicality of the way in which I work and work on the floor. I work really close to these drawings. I relinquish the control of the hand. It’s not about the precious fidelity of the mark … it’s about relinquishing to the miraculous, what comes of that moment.”

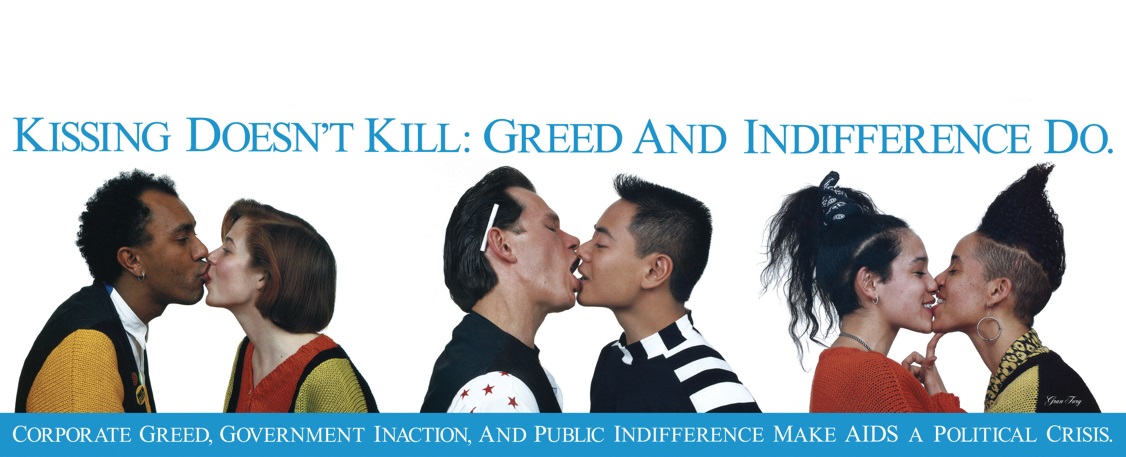

Of course, it would be difficult to speak of love and intimacy without mentioning their antitheses. Goliath characterised her past work Elegy (2015), as a lament-driven work that addresses fatal acts of violence against women while avoiding the perpetuation of trauma. She said, “I did not want to return to the scene of subjection, I did not want to repeat the violence.”

At the nexus of art and violence, Mohale skillfully identified space for Femme rage, saying “ … in the wake of so much violence enacted upon my own body, it was really important for me to think it and hook it up to Empire … Not just these giant spectacular eruptions of violence, but legacies of violence.” Drawing inspiration from Glen Coulthard’s concept of “righteous rage,” Mohale invited us to view rage as a tool for Black Femme resistance.

Mohale prompted Goliath to reflect on the implications of portraying Winnie Madikizela-Mandela in this show. For a while, the pair lingered there and we saw something of a rupture in the way the two saw rage, with Mohale remarking, “I enjoy how my understanding of rage differs from you.” Goliath went on, “ … for me, what is really interesting with Madikizela-Mandela’s portrait specifically, is I find it very vulnerable. … it’s magisterial, but there’s a resignation … when I look at her.”

One of the seemingly many roots of the strong intellectual chemistry between Goliath and Mohale was the impact of Christina Sharpe on both of their work. Goliath’s encounter with Sharpe’s Monstrous Intimacies (2010) brought her towards an understanding of violence as both spectacular and insidious. Goliath insists: “We may need to bear our rage, and allow it to be transformed into the possibility of something else.”

In an audience-pleasing turn, Mohale asked Goliath about her portrayal of artist Desire Marea. As Mohale notes, “Desire being an initiated Sangoma is also not a footnote. … so much of their spiritual power is ancestral, is linked to bloodlines. … I think the sense of the sublime is also something that I chase in my own work, but … I’m seeing the clear instances and connections that are happening now between … contemporary queer artists.”

The intimate intellectual interaction between Goliath and Mohale prompts a collective reconsideration of the role of rage in desire and queerness in African artistic practices. It also did the long and thankless work of taking up space in an almost impervious institution. As we looked around the room and saw reflections of ourselves, both in the flesh and on the walls, we allowed ourselves to yearn for, perhaps even celebrate the dynamic and precarious possibilities within Black queer existence. Even amid this briefly beautiful moment of perceived reprieve, we were reminded of the violence that surrounds us as Mohale closed the discussion with a steady citation of Gabeba Baderoon’s War Triptych (2004).