Lelo What’s Good is a Johannesburg-based multidisciplinary creative that got into DJing unexpectedly. He met FAKA‘s Desire Marea while living in Durban. Upon returning to Johannesburg to study, he got to know Fela Gucci who invited him to play at Cunty Power.

“I decided to come through and play. That’s when it started. After that I started getting booked, which was a bit hectic. I didn’t plan for it to be quite honest,” recalls Lelo. The gig led to him being invited by Pussy Party‘s Rosie Parade to attend DJ workshops in order to hone his skills. “I went to her and we just hit it off and she really helped me a lot in starting this new adventure that I was going on. Before I knew it, I was on lineups, people asking me to play places. It’s been interesting.”

Fascinated by music videos from a young age, Lelo was exposed to artists such as Missy Elliot, Aaliyah, Destiny’s Child, Beyonce, D’Angelo, Lauryn Hill the Fugees as well as local artists such as Lebo M, Zola, Boom Shaka & Brenda Fassie. As a DJ, he likes to push an alternative, grungy sound that draws a lot from ballroom and underground UK warehouse music as well as the raw sounds of Durban’s gqom.

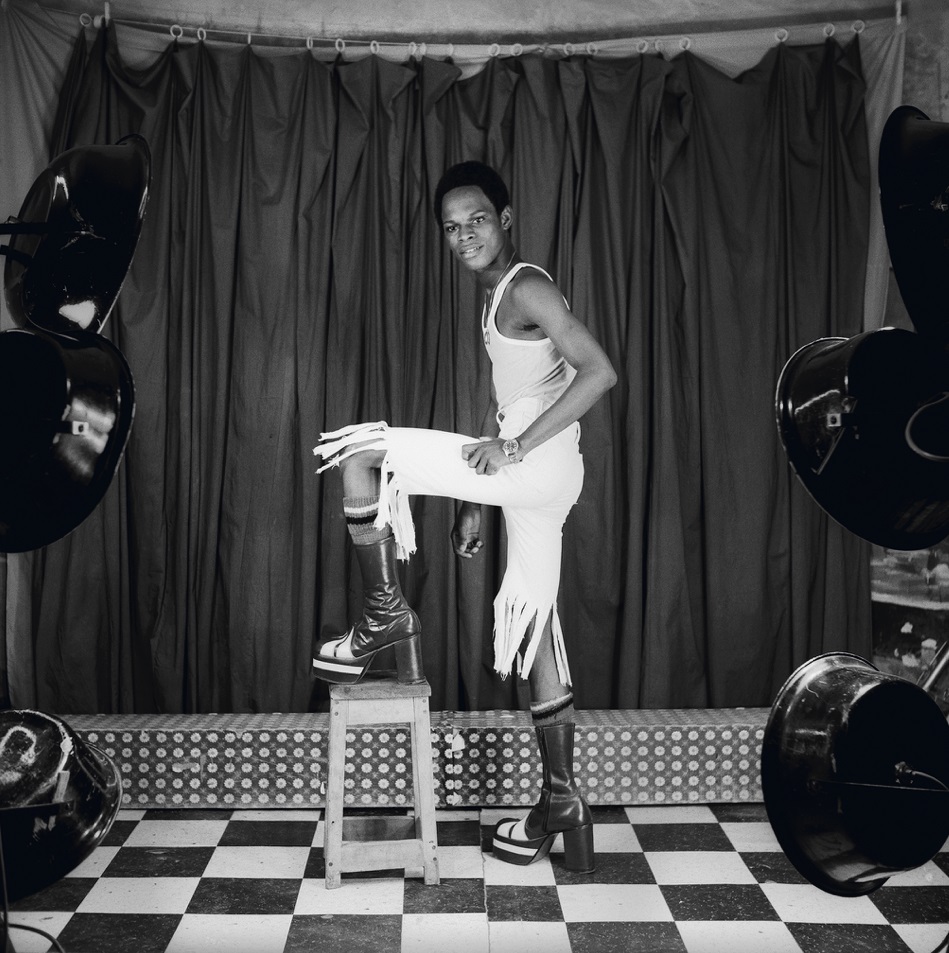

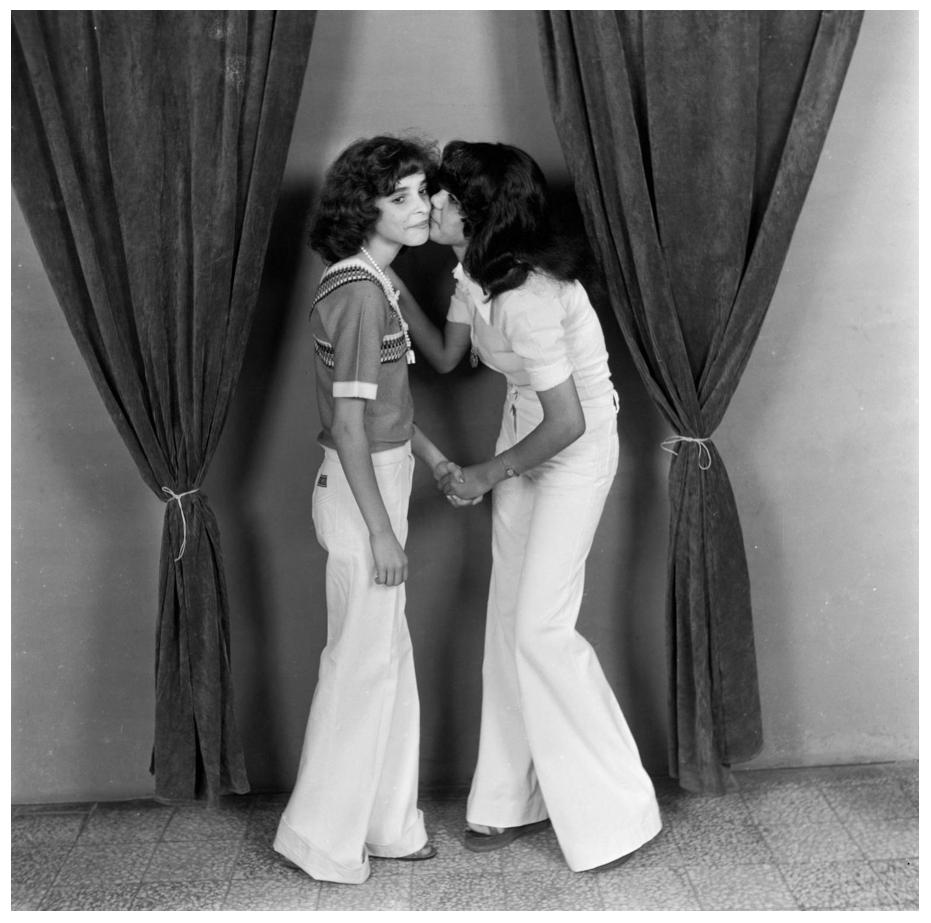

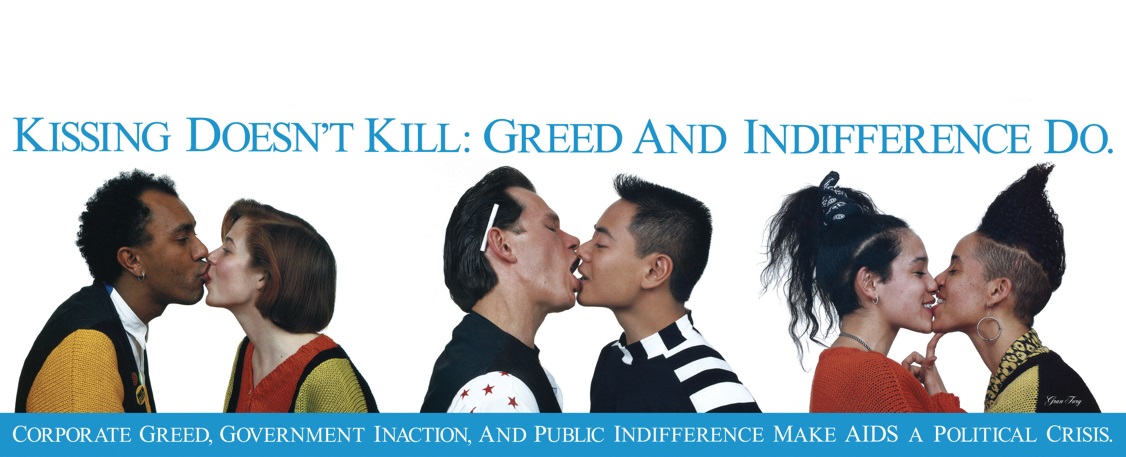

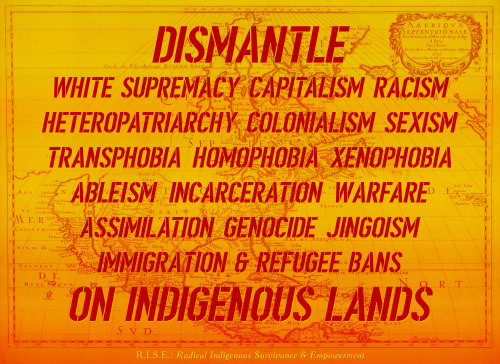

Thanks in part to his affinity for ballroom music and a desire to create safe spaces for the queer community, Lelo What’s Good founded Vogue Nights. This saw him bringing New York’s ballroom subculture to life in South Africa. “The ballroom scene in New York shifted culture, it uplifted the LGBTQI community into what we know it [to be] today. If you look at it now there’s ballroom all over the world, Berlin, Paris, London, and we don’t really have one here. So I thought since I play ballroom type music and there aren’t a lot of safe spaces for us to actually venture our bodies in, so why not create a space that speaks for us and is by us in the city and also take it around the country. Because we never really had that. So it’s a response to that. An urge to create more safer spaces.” explains Lelo.

Beyond the parties he throws and the music he plays, Lelo What’s Good aims to be a representative of South African queer culture. “I think I do represent the people in my community to mainstream media. Everything that I’ve written is about queer artists or safe spaces and things like that. I do my best to accurately represent the times that we are in now as queer people, in queer bodies, whether it be as artists or the person down the road and how they might be feeling. I think that’s the type of content I’m trying to create, to write about and speak about. Even the places that I DJ at, they have to be 100% safe for femme bodies and queer people. It’s really important.”