Coloniality describes the hidden process of erasure, devaluation, and disavowing of certain human beings, ways of thinking, ways of living, and of doing in the world – that is, coloniality as a process of inventing identifications – then for identification to be decolonial it needs to be articulated as “des-identification” and “re-identification, which means it is a process of delinking

This statement by Walter Mignolo during a 2014 interview with Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández describes the pervasive nature of coloniality. Certain parallels can be drawn between the tragic events of June 16th, 1976 and the recent Fallist Movement. These historical moments have enacted ruptures of resistance. Recognizing moments of erasure is crucial to redefining historical narratives and addressing systemic disparities of power. However, ‘the voice’ of youth is not merely a homogenized entity. Issues of representation require a nuanced and considered approach – allowing passage to spaces that have been previously inaccessible. Within the context of contemporary art in South Africa, opportunities for self-representation and exploration are often scarce.

It is in response to this, that Bubblegum Club has created an annual micro-residency to cultivate the talent of young artists. A group of four womxn have been selected for this years programme – to participate in a series of workshops, close conversation and ultimately exhibit a new body of work at the end of June. The programme has been conceptually framed around decolonial options – to tentatively consider and critique this notion beyond the buzzword.

Jemma Rose, a self-identified visual activist and Gemini, uses her camera to capture daily realities. She also uses it as a mutual point of contact – a device to generate encounters with people. Photographic work is in part a family tradition, it has always had an element of familiarity to it, as both her father and grandfather have engaged with the medium.

Through her work she often works with themes of queerness and queer identity as well as drawing attention to mental health issues. Jemma notes that there are some performative qualities to her photographic work and usually focuses on using her images to convey a message relevant to her experiences. She is interested in locating herself and her work within a larger context based on her personal subjectivities.

“I initially thought of ‘decolonisation’ in relation to breaking things down. I’m starting to realize that it’s much more than that. There are so many things behind it that you have to unravel…masculinity, heteronormativity and sexism are also all part of it. You need to slowly start unraveling it so that you can see the bigger picture.”

This sentiment echoed by Mignolo “Patriarchy and racism are two pillars of Eurocentric knowing, sensing, and believing. These pillars sustain a structure of knowledge.” (2014). Thus through untangling the history of colonization, racisim and the patriarchy must also be addressed.

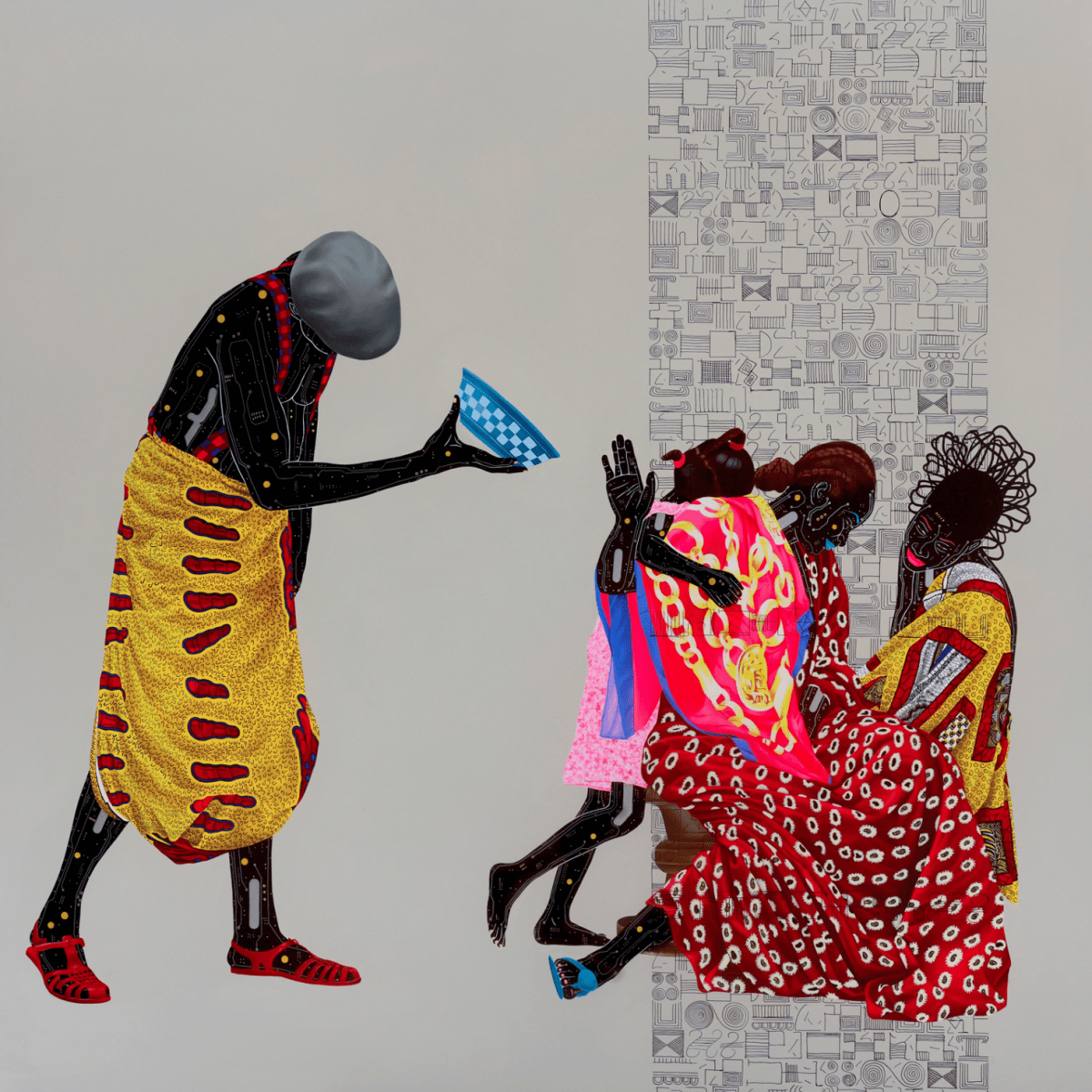

Boipelo Khunou is currently in her final year of Fine Arts at Wits. “It’s been an interesting journey trying to find out what this so-called-fine-art-world is – what it means to be making art and making work.” This process can often be dissolusioning, especially once you realise how the elements of capital and nepotism are entertwined in the system.

As a multi-diciplinary artist, Boipelo focuses her practice on photography, print and digital media. Thematically she works through ideas of personal power. “I use to reflect about the things that I experience. Experience is one of the most important parts of my work.” Through her work she investigates the kinds of spaces it is possible to find and claim power. She describes how oftentimes it’s within the walls of the institution that power is forcibly relinquished and autonomy is lost.

“I didn’t know anything about decolonization until Fees Must Fall.” During the movement, the concept gained an immense amount of traction. Pedigogical systems and western epistemology within the university and beyond were challenged. “After the protests, so many people I know went through this weird depression because they realized that institutions have so much power, but what does that mean for people who want to dedicate their lives to decolonial practices?.”

“The interesting thing is to actually see how you can put decolonization into practice. You can do all the readings, go to the talks, go to all these places that advocate for it, but what does it mean to practice it every day? I think that it is a very complex thing, it’s something that challenges me. You realise that there are so many aspects of your being and how you operate in life that you need to figure out how to prevent institutions and conditioned ideas to creep back into your life – it’s a constant battle.”

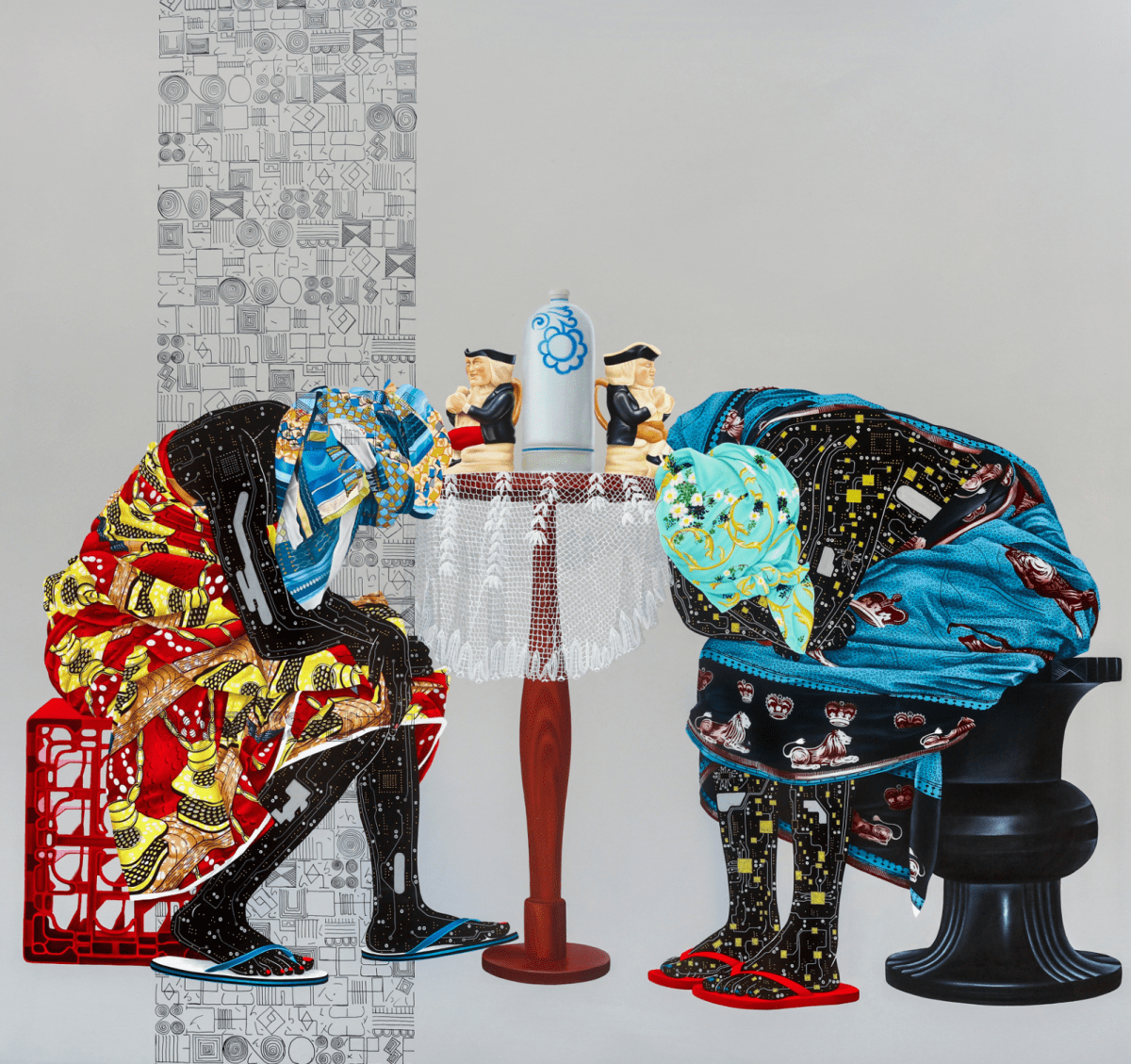

Natalie Paneng is a 21-year-old artist and student. Her background in set design gives her a unique application of her use of space. Her work is often located virtually as she explores what it means to engage with the internet as a black womxn. The mode in which she does this is often through the use of alter egos. Hello Nice is a character she created on youtube and utilizes the ‘vape wave’ aesthetic.

Recently Natalie created a zine called Internet Babies, it chronicals the profiles of five girls: TrendyToffy @107_, Black Linux otherwise known as the Mother of Malware, Silverlining CPU, Fuchsia Raspberry Pi and Coco Techno Butter. It explores their relationship to digital space and how they’re the “fiber of the internet.”

She decribes how, “trying to find myself is like the decolonization of myself. Learning how to push those boundries and be more radical as well as owning the need for decolonization and acknowledging that it’s going to have to start with me.”

Tash Brown is a young painter who approaches the concept of White Suburbia as well as investigating her place and participation within that space. While working through the lens of decolonization she describes how “white suburbia becomes a distortion of reality”, one which is also often still racially segregated. Her distorted paintings are often a grotesque depiction of the suburbs.

As a white artist, she is critical of her own voice. Noting that, “it’s a time and a space in South Africa where black artists should be prioritized. So I guess I’ve struggled to find myself relevance in the art world, but through the critique of my own cultural issues and the problematics is a way that I can approach it, without having my voice crowding out other voices.”

Credits:

Photography & Styling: Jamal Nxedlana

Makeup: Orli Meiri