According to the World Economic Forum 15-20 million young Africans are expected to join the workforce every year for the next three decades —begging the question; what opportunities will exist to allow these young individuals meaningful work; work that is challenging, impactful and unexploitative.

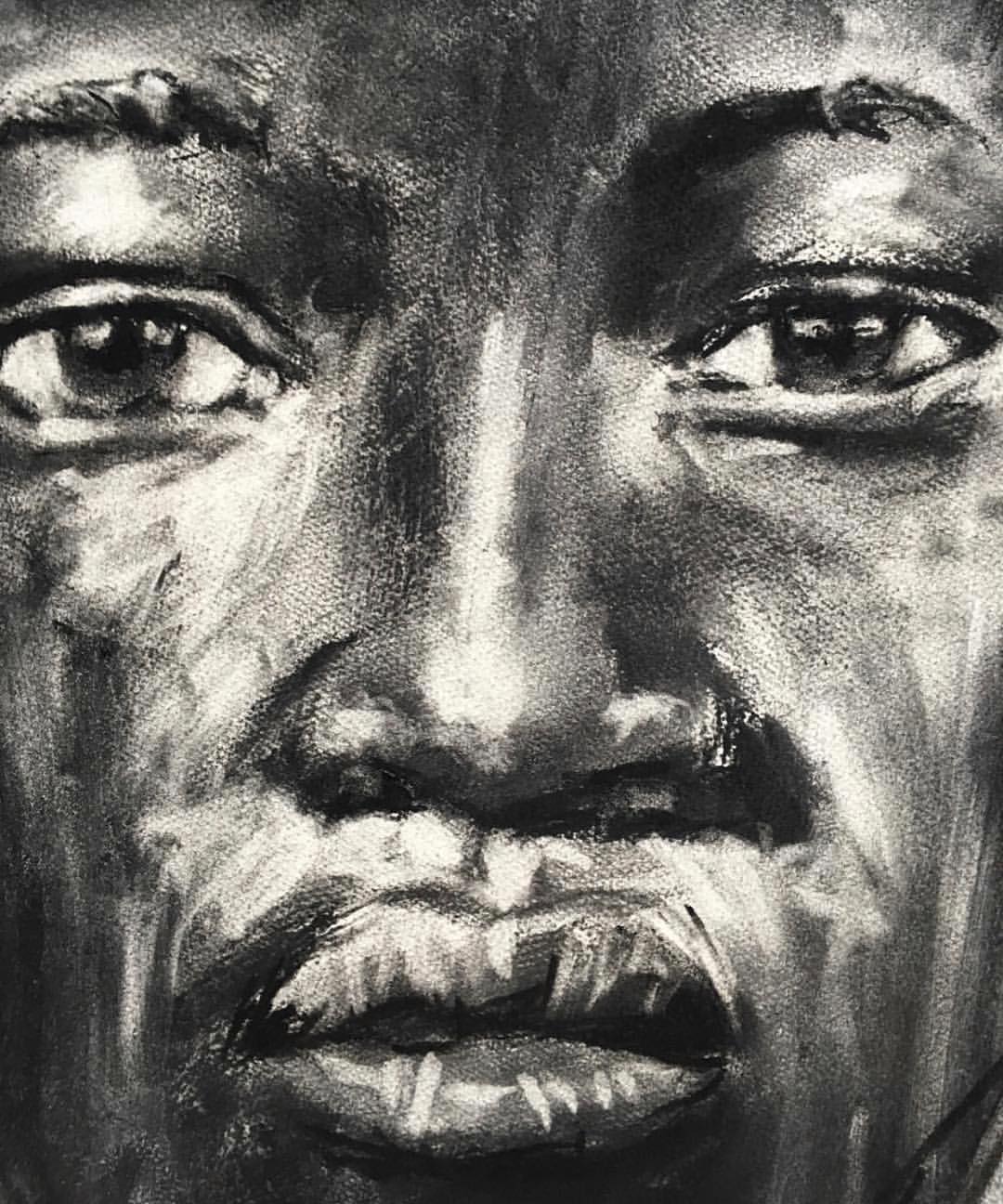

Surviving as an independent artist has always been a particularly difficult endeavour. In an increasingly difficult economy thronged with high levels of unemployment and competition, artists find themselves at wit’s end on how to survive while earnestly pursuing their work.

The 2018 South African Wealth Report estimates the global top-end art market for African Art accounts for US$1 billion, of which US$450 million (R5.5 billion) is held in South Africa specifically. The report estimates that South African art prices have risen by 28% over the past 10 years (in dollar terms) far above the 12% rise in global fine art prices. However, the manner in which this creation of value is distributed remains skewed — with very few leading artists at the top; Irma Stern, Maggie Laubser, JH Pierneef, Alexis Preller, Gerard Sekoto, Hugo Naude, William Kentridge and John Meyer. It is unfortunate that the art world mirrors the rest of society in terms of how value is created and how the cake is divided.

What are the tenets of a sustainable career in the arts? In which ways are artists at differing levels of experience and “success” sustaining their careers and their lives? Through engagement and conversations with artists across various mediums and platforms; from those who recently left art school to those with decades of experience in the art world, (specifically fine artists practicing in photography, filmmaking, painting, printmaking, performance art and writing), I fill in this context and my own observations.

What instantly became clear is that pursuing a career in the arts and opting to remain independent requires dedication and commitment and should be inspected through the lens of entrepreneurship.

The blended approach

Many artists opt for the blended approach in terms of how they make money. They seek to work with a range of brands and corporates over and above passion and personal projects. Many are open to part-time work as well as other work outside of the industry as a strategy to supplement income; this ranges from tutoring, baby-sitting, retail and working for institutions and galleries.

A stable source of income is seen as an important component to creating more spaciousness as they work on strategies for a more scalable income.

“The secret to working part time is finding something that grows, teaches and inspires you. Outside of film my first career opportunities came from galleries to create performance artworks – specifically avant-garde Hollywood-genre immersive narratives.” – Emma Tollman (writer, singer/songwriter, actress).

In the same light, some artists are able to fully fund their work and their lifestyles without needing to supplement with additional work. Factors such as; length of time spent in the industry, visibility and a substantial portfolio contribute to where artists find themselves on the part-time/full time artist scale.

“I try to balance freelance and corporate work. Corporate always pays better and on time, but it is often not the most exciting thing. Freelance is often great because you have the luxury to pick what you want to work on.” – Lidudumalingani Mqombothi (writer, filmmaker and photographer).

Additional avenues which can provide a source of income include residencies, prizes and grants from art institutions as well as the government.

Understanding the market

Artists feel the pressure as they tug between making work that is commercial and work that is more honest, a constant negotiation between authenticity and relevance. Commercial work sometimes results in overproduction —prioritising sales over growth and experimentation.

A key observation is that South African art buyers tend to be rigid in terms of what they’re looking for; there are very specific narratives and aesthetics that the market is interested in, making it very difficult for more conceptual and experimental artists to succeed financially.

Brands and corporates are also less open to risk; they gravitate towards artists that already have a strong following and a certain level of visibility —a popularity trap that results in brands approaching the same “trendy artists”.

“Usually those spaces are looking for trendy or cool people or work that is ‘accessible’ in ways that one can exploit the term. There’s a particular aesthetic that such commitments require.” – Nyakallo Maleke (multidisciplinary artist in installation, printmaking, sculpture and performance).

It is difficult to conclude with certainty what factors exactly will result in success. Is it the quality of the work, social capital, seizing opportunities as they occur or merely an air of celebrity? However, we speculate that some level of awareness of industry dynamics and politics allow different artists the ability to navigate with agility and to plan around ways in which they can approach opportunities.

“By grade 12, I was already selling designs and charging consultation fees, I started exhibiting my work in my second year — that became one stream of income. I think diversifying my practice has also helped financially.” – Banele Khoza (Visual artist).

Administrative competence goes a long way in ensuring a more professional art practice, which often has a bearing on the type of work and clients artist work with. Quite simply, these include:

- the ability to price work fairly and appropriately

- client acquisition strategies

- securing a reliable support team

- sending quotes and invoices on time.

Thinking for the future

Sustaining an art practice requires investment through time, mentorship and training. A contested issue among artist is the idea of working for free — while some artists use this as a long-term strategy to build a considerable portfolio, others refuse on principle. A resistance towards the exploitative nature of brands, corporates and institutions.

“Sometimes you need to weigh up your options and see what would be sustainable for you to gain; what would be beneficial as an opportunity in the long run. Sometimes you need to turn down a gig, especially if the client wants to underpay you or doesn’t see the value in what you do. It’s also okay to take a break to work a 9-5 so that you can plan further for your future and really focus on where you want to be after that.” – Nadia Myburgh (recent graduate and photographer).

A key theme that emerges is the importance of saving; many of the artist we spoke to mention this is a key learning area in their journey. Saving allows greater freedom where a highly unpredictable and precarious income stream is a reality.

“I’ve learnt along the way to always stay true to what I want to achieve and to let go of fear. I was afraid of how long it would take me to get on my feet without a 9-5 or how I would be able to sustain myself. Sometimes you’re held back by financial constraints as well as time constraints but also by fear. I’ve learnt that I need to be fearless and brave.” – Malebona Maphutse (Printmaker, photographer and filmmaker).

Social Media to generate professional currency

More and more artists are embracing social media as a way to enhance their marketability and reach. They continue to use social media (to varying degrees) as a way to make their work more accessible while drawing in new audiences. “Social media and galleries play an important role in exposing my works to potential buyers; both local and international.” – Themba Khumalo (Visual Artist).

Social media is often the vessel through which many collaborative efforts are cultivated. Artists are pointing to the importance of learning and growing together whilst also alerting each other to opportunities that can be financially beneficial. They are pointing towards ideas of honing your skill and making yourself more marketable and thereby creating a competitive edge.

“Collaboration creates space and a platform for people to share ideas and tackle difficulties. But I think it’s difficult when we are still obsessed with this myth of the genius, we idolise creatives and put them on a pedestal. I think that can be a hindrance to collaboration. You kind of [have] to do your own thing and benefit from it alone, monetary or otherwise, but there is something to be said for collaboration. You can create a bigger network in that way.” – Nikita Manyeula (Masters student at the University of Witwatersrand).

Through this process of conversing with artist about the often, unnamed pains and joys of building a sustainable art practice, I was able to gain some insights into the different possibilities of navigation. Although there are no easy or guaranteed answers, keep in mind the key takeaways; be patient, save money, understand the dynamics of the industry and invest in the work. I am inspired by the idea of celebrating small victories as a way to sustain energy and passion – a simple concept that allows emotional and mental wellbeing.