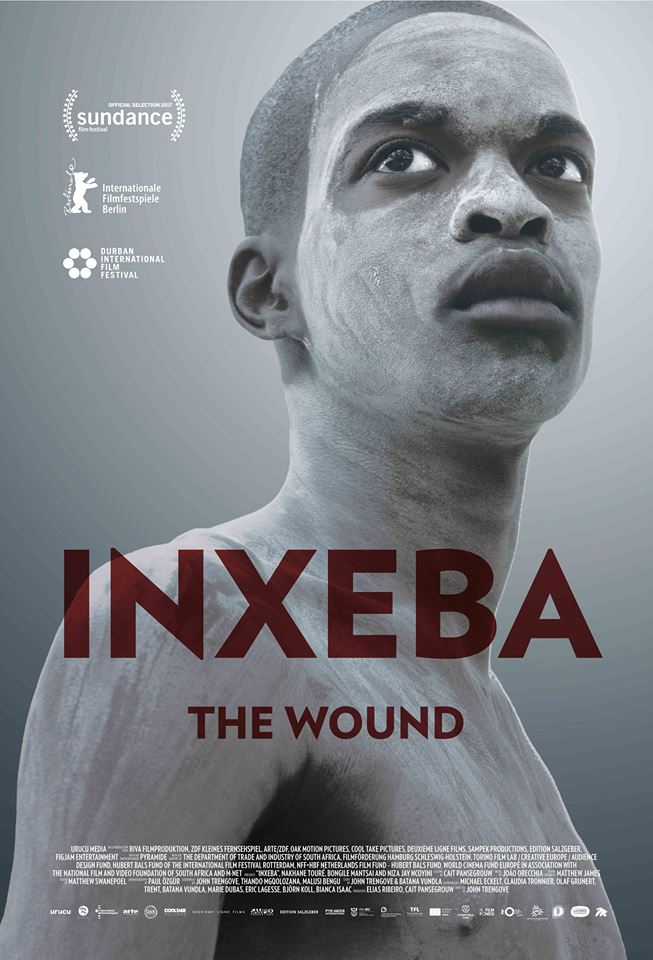

Warning: This article contains spoilers from the film, Inxeba (The Wound).

Set in the scenic mountainous Eastern Cape emerges Inxeba, a powerful, moving and thought-provoking South African work of art directed by John Trengrove. This daring and unsettling film narrates the intersectional story of an uninspired and lonely Xhosa factory worker Xolani (Nakhane Touré) who joins the men of his community to initiate a group of teenage boys into manhood (a process known as ulwaluko). As Xolani embarks on the journey of being a caregiver during the initiation period, he encounters Kwanda (Niza Jay Ncoyini), a sullen yet defiant and disruptive initiate from the city of Johannesburg who urges Xolani to interrogate his queer identity.

Inxeba is essentially a revolutionary tumultuous gay love story between two caregivers Xolani and Vija (Bongile Mantsai) which takes place in a violent, patriarchal and hyper masculine environment. It explores compelling themes concerning homosexuality, the construct of Xhosa masculinity as well as the colliding juxtaposition of modernity (represented by references made to the city and the effect it has on those that have left their rural homes) and tradition. Unfortunately, we live in a society where most instances of violent behaviour committed by men go unchecked which begs the question of how we should transcend violent masculinity in such spaces. This film is revolutionary in numerous ways as it protests toxic masculinity and patriarchal cultural norms, it exposes deep-rooted homophobia and it fundamentally opens important and difficult conversations.

The sublime cinematography manages to beautifully capture pain, love, affection, fear and rage all at once. One of the most mesmerizing moments in the film comes from the scene by the waterfall which showcases the passionate black Xhosa male lovers (Xolani and Vija) embracing one another, kissing, cuddling and being affectionate. This moment proves to be ground-breaking and encapsulating as it defies the rigid social norms and homophobic views that are held by some men.

Viewers also get to witness the blossoming friendship between the caregiver and initiate. In a strange but organic way the initiate becomes the teacher when he drives his caregiver to confront his truth and sexual identity. The initiate plants the seed of learning and unlearning for his caregiver to which his caregiver rejects and ultimately chooses to return to his former life. The act of silencing is a common theme that reoccurs throughout the film. Kwanda is constantly silenced when he problematizes Xolani’s hypocrisy or even when he calls out Xolani for having an affair with Vija who has a wife and children back home. Kwanda’s opinionated and outspoken nature ends up being his detriment. This sets a strong precedent that being outspoken and fighting for what you believe in can get you killed. In the end, the unsafe environment that Xolani and Vija find themselves does not grant them with the opportunity to truly and freely love each other. They would rather pursue great lengths to protect their secret than taking the risk of being exposed, shunned and ostracized.

Inxeba is bound to evoke feelings of shock, resentment, despondency and inquisitiveness which will take time to unpack, process as well as have honest and uncomfortable conversations whether it be on the dinner table or on social media. This film is imperative for the representation of the LGBTQ+ communities and that cause should not be derailed by cis-het fragile men. The representation of the queer community and queer issues in infinite versions matters. It also serves a crucial role of dismantling patriarchal cultural norms. We should ultimately never use culture as justification to dehumanise, oppress and subjugate marginalized folk (in this case queer folk) and if culture commits such acts of violence, this desperately needs to be tackled as well as problematized.