The Wits Art Museum (WAM) recently hosted a walkabout on their latest exhibition Arte Povera and South African Art: In Conversation led by Consul General of Italy in Johannesburg, Dr. Emanuela Curnis, and South African curator, Dr. Thembinkosi Goniwe. The exhibition includes two sections, and while I was excited to see the works of Italian artists like Pino Pascali irl, my curiosity focused on Goniwe’s take on the impact of Arte Povera on South African art. As a long-time Arte Povera Stan, I believed it was this perspective that made this show seminal.

Coined in 1967 by Germano Celant, Arte Povera, is an Italian avant-garde movement. Directly translated as “Poor Art,” Arte Povera challenged historical art’s exaltation of luxurious materials and pristine gallery spaces. The movement opted for non-traditional materials often found in homes or nature, emphasising a love for ordinary objects, lived experience and the human body. Its unfettered use of accessible materials reflected an interest in physicality and explored environmentalism in art, long before it became popular.

Arte Povera 1967 – 1971, is the first exhibition of its kind in Africa. Curated by Ilaria Bernardi, this segment highlights 13 renowned Arte Povera artists, Giovanni Anselmo, Alighiero Boetti, Pier Paolo Calzolari, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Mario Merz, Marisa Merz, Giulio Paolini, Pino Pascali, Giuseppe Penone, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Emilio Prini, and Gilberto Zorio.

On the other hand, Thembinkosi Goniwe curated South African Innovations, 1980s – 2020s is something of a response on behalf of the 13 South African artists Jane Alexander, Willem Boshoff, Bongiwe Dhlomo, Kay Hassan, David Thubu Koloane, Moshekwa Langa, Billy Mandindi, Senzeni Marasela, Kagiso Pat Mautloa, Thokozani Mthiyane, Lucas Seage, Usha Seejarim, and Kemang Wa Lehulere.

Walking around the exhibition, one got a strong sense that the two exhibitions were quite disjointed, which is not necessarily a bad thing. After briefly engaging downstairs with the Italian part, Goniwe guided viewers through the upstairs South African exhibition, drawing attention to the significance of the artworks’ construction and thematic elements. As he walked about, he emphasised the artists’ deliberate choices in materials, exploring how these choices both echo local narratives and resonate with global issues.

For instance, Goniwe explained Usha Seejarim’s The Modest Home Builder (2004), which involves collecting bricks and wrapping them in a fabric known as Shweshwe—a process reminiscent of ancient practices, transformed into contemporary art. According to Goniwe, the use of African fabrics and local patterns, such as those associated with Xhosa women and domestic workers, becomes symbolic and intertwined with the broader narrative.

by Usha Seejarim

As I listened, I noticed an absence of the work of artists like Bronwyn Katz and Lungiswa Gqunta, which I would more readily associate with Arte Povera. I asked Goniwe: “As we can see in this exhibit, there’s a lot more manipulation of materials, transforming them into new intricate forms. This differs slightly from the traditional Arte Povera approach, which is often more reverent towards the material. Can you explain this curatorial choice?”

He responded, “Mimicry implies a lack of originality as if we have no inventive capacity of our own. Instead, I aim to create a parallel discourse, one that reflects the unique evolution of material manipulation in South African history. … This question of historical materiality is so strong in Black theories. … Downstairs, even if you’re talking about how in the 60s there were protests … there’s a kind of a different conversation and an artwork and a process that happens … you see the politics that’s happening and the way in which they imagined it throughout. So that’s why I find it very hard to grapple with inheriting ways of thinking from white people.”

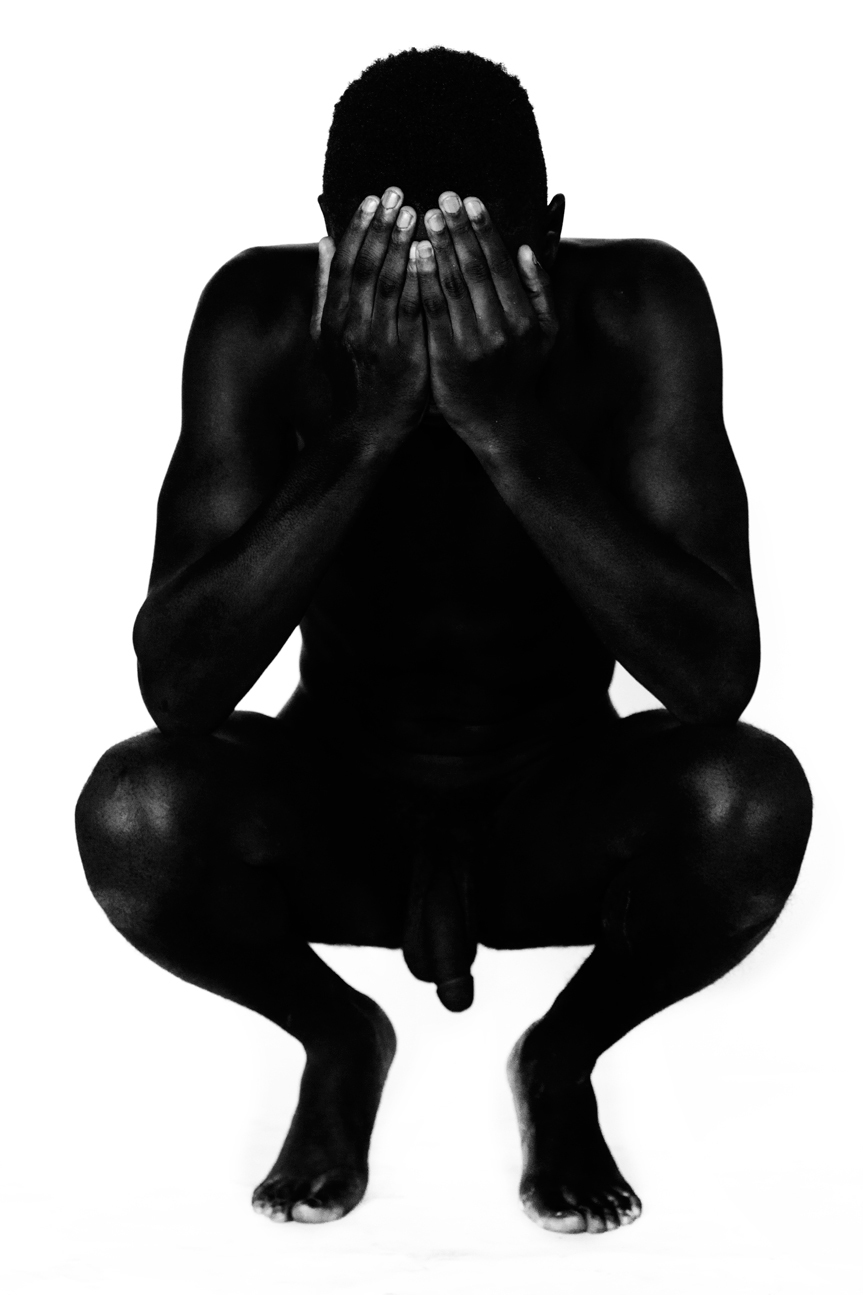

True as his response may be, in this context, it is still quite thrilling for the viewer to discover unquestionable visual parallels between Arte Povera and South African art. For me, Lucas Seage’s Found Object (1981) seemed to most epitomise Arte Povera.

Goniwe lingered here, saying, “… there’s a profound concept in being born and dying in a bed. … Seage, not bound by formal education, challenges conventional artistic materials. This echoes a broader tradition found in societies where people constantly create and curate, whether through changing living spaces or cultivating gardens. The professionalisation of curating seems to overlook the innate creativity present in everyday practices …”

by Lucas Seage

by David Koloane

Touching on his muse, Koloane’s Saxophone on a Wheel (1983), Goniwe continued, “What Thupelo does, it allows artists to emerge in the materiality of things. If anything, we’ll come closer to Arte Povera as a movement … However, defining movements is challenging, as artists are often ahead, and historians, curators, and critics lag behind. …

It seems as if we fear to name ourselves. We fear to title ourselves. … But the beautiful thing now is a new generation of scholars, especially African-Black scholars, who are beginning to name what they do. ‘Innovation’ is an open-ended title intentionally chosen to encompass the various trajectories present in the exhibition.”

When I asked Goniwe to speak on the economic challenges faced by artists in Italy during the post-war period, leading to the emergence of Arte Povera, and how this could highlight more potential connections between this historical context and contemporary South African art, he responded: “Let me clarify: I’m not saying that these artists are working under poor conditions. To start with Italy in (the) 1960s is not a poor country. … What I’m emphasising is the conscious choices made.”

Not entirely satisfied with this response, I rephrased my question, linking it this time to so-called “Township Art”. While it lacks aesthetic similarities, Township Art does illustrate my interest in the connection between socio-economic conditions and the production of art.

Goniwe answered, “When we talk about privilege, it’s about those who can afford to experiment … It’s not a performance; it’s an undeniable reality. We need to be mindful of this … To answer your question about why we didn’t explore Township Art, it’s because our interests were tied to museums.

It wasn’t just about money; it was also about time and value. Fiona can elaborate on the constraints and limitations we faced. We don’t make excuses for what we could or couldn’t have done; we focus on what we did. Any other critiques are welcome, and so are extensions of the project. I want to make it clear; I’m not defending against criticism. We are actively revisiting concepts, including Township Art, as part of our ongoing projects …

The failure lies not so much with the artists but with us—art historians, critics, and theorists. Because we don’t read carefully. As I said, if you ask me, Township Art is a movement … There are also other movements like the Funda movement, which focuses on aesthetics and art foundations. Artists working there share certain characteristics that we haven’t explored due to our tendencies to compartmentalise or depend on existing narratives.

So part of revisionist history, it must be critical, salvage and mine and give it a different meaning. With this exhibition, my intention is to open up a dialogue. It’s an opportunity to reflect on South African art over the past 50 years … in a way that has not happened yet.”

Goniwe is spot on. While artists have always worked with whatever materials were available due to financial constraints, this legacy has not been adequately addressed in the local context. This exhibition, which remains on show until the 9th of December, not only highlights the need for further scrutiny of the socio-economic impacts on materiality in South African art but also underscores the necessity of cultural exchange for rich artistic development. That is why, while it has plenty of room to grow, Arte Povera and South African Art: In Conversation is undeniably paramount.