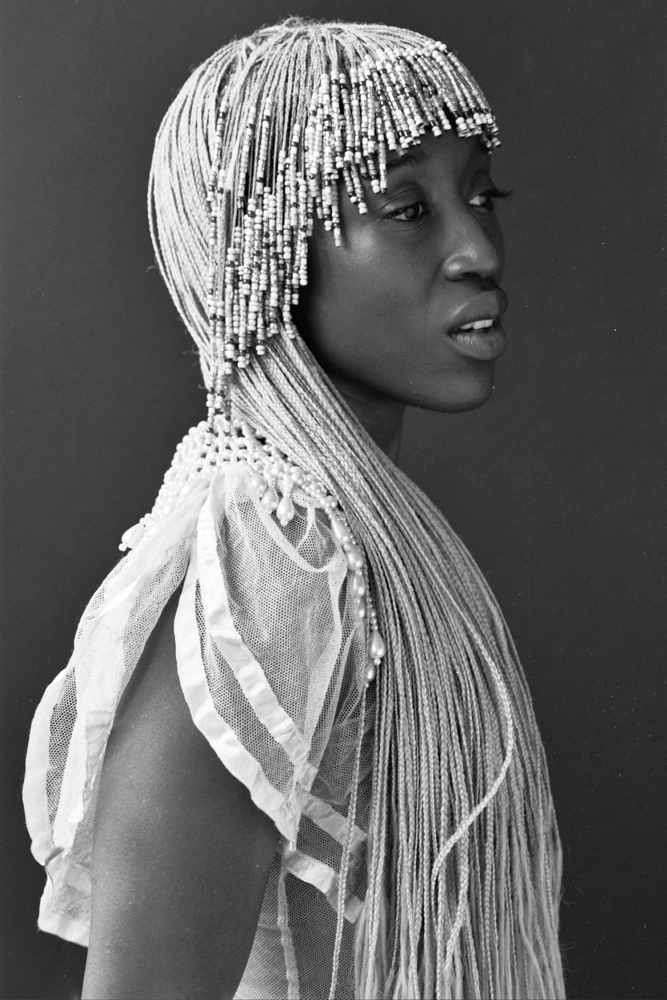

The exhibition Umlindelo wamaKholwa features the work of multiple prize-winning and internationally exhibited Johannesburg-based photographer Sabelo Mlangeni. The exhibition is a collaboration between Mlangeni and Dr Joel Cabrita, a historian based at the University of Cambridge, and is accompanied by a 128 page catalogue. Having shown at Cambridge, the exhibition is at WAM, curated by Kabelo Malatsie. I interviewed Mlangeni to find out more about his collaboration with Cabrita and the images selected for the show.

Could you please share more about the cover for the catalogue and the symbol that appears on it?

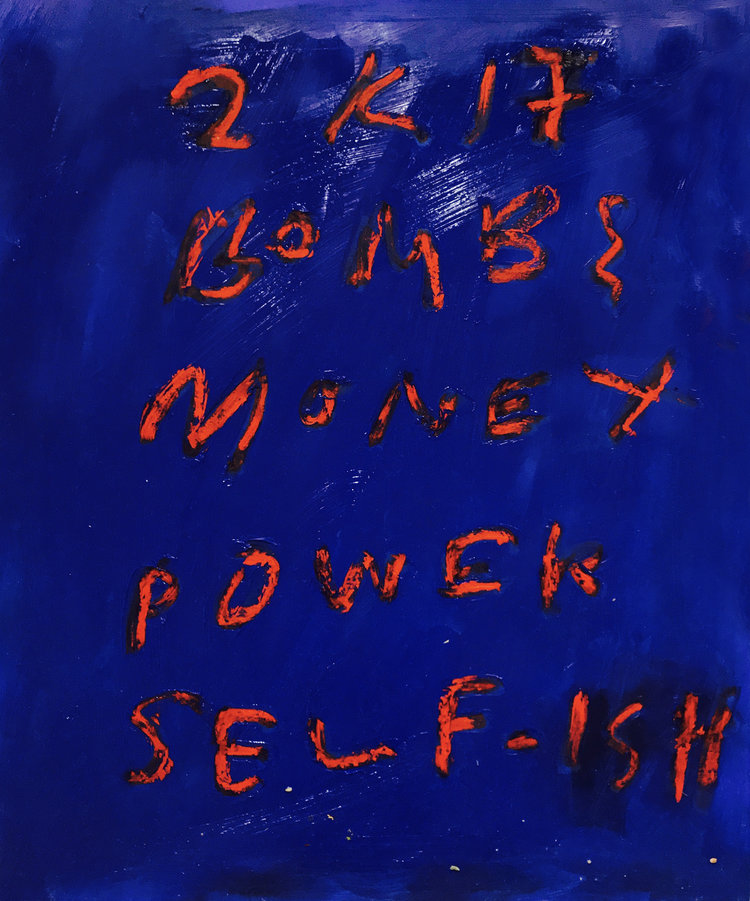

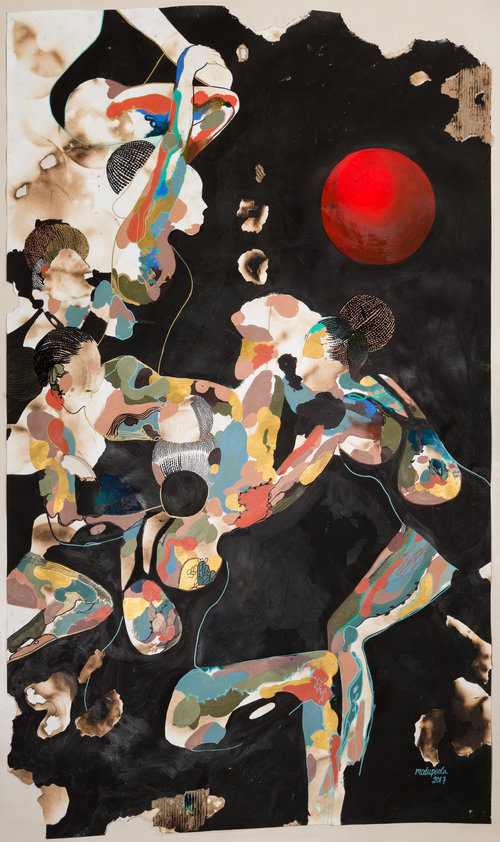

For a long time I’ve been interested in the other world that we access through the visions of healers, prophetesses and prophets. Some years ago a vision came to me through them about a great ancestral spirit that had something like a ‘gift’ for me. But whenever the spirit was ready to give it to me, it found me not in the right ‘place’. So the symbol on the cover of the catalogue is that gift. We also find this symbol in the entrance to the exhibition space at WAM, presented as part of iLadi (a Zionist altar cloth). This iLadi was erected as my own personal response to this vision.

The title of the exhibition and your own spiritual awakening are tied together. The people and the spaces you photograph are also well known to you. Please unpack the importance of the insider perspective you present, particularly for subject matter that has often been explored and represented by people from the outside?

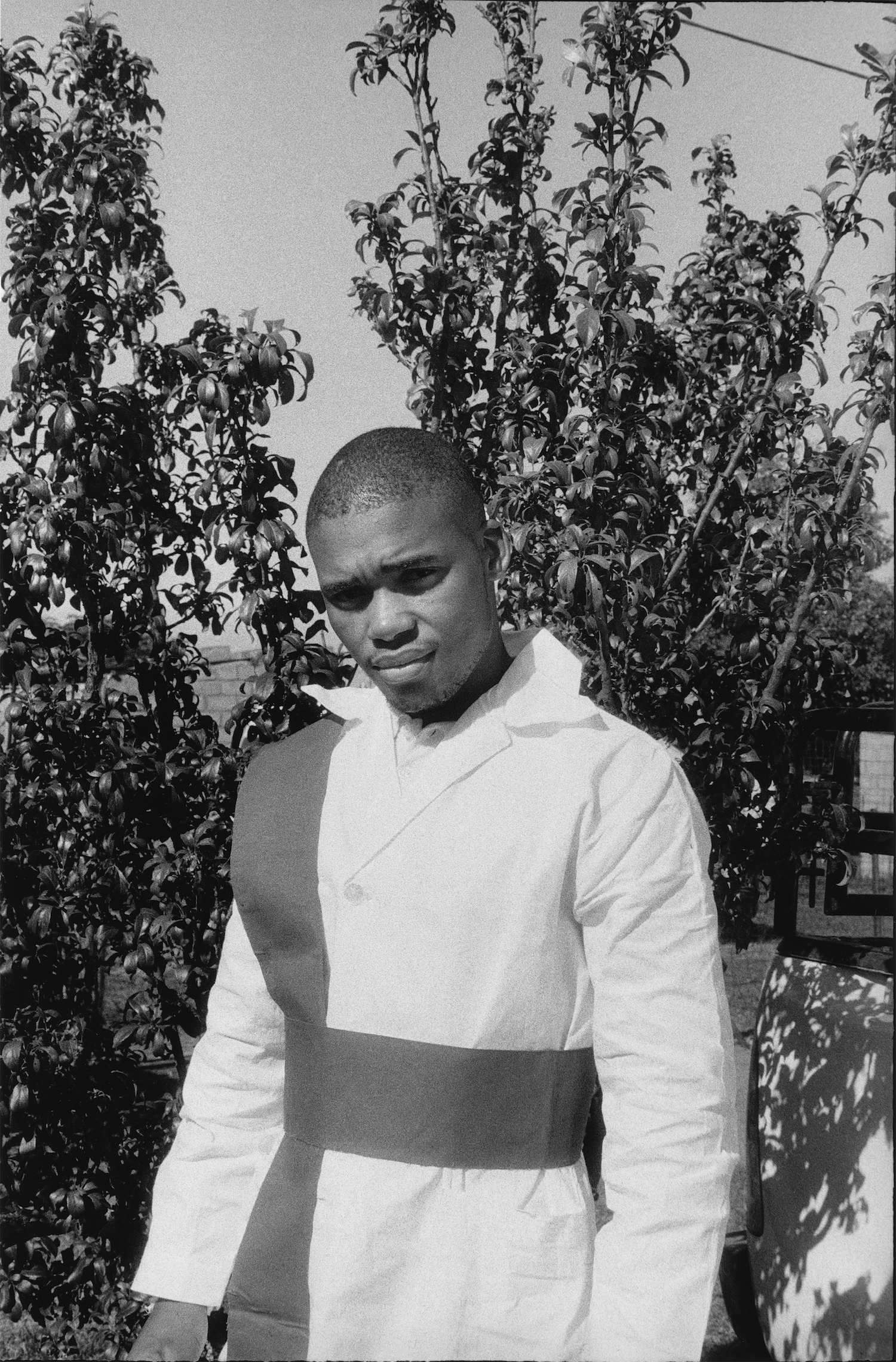

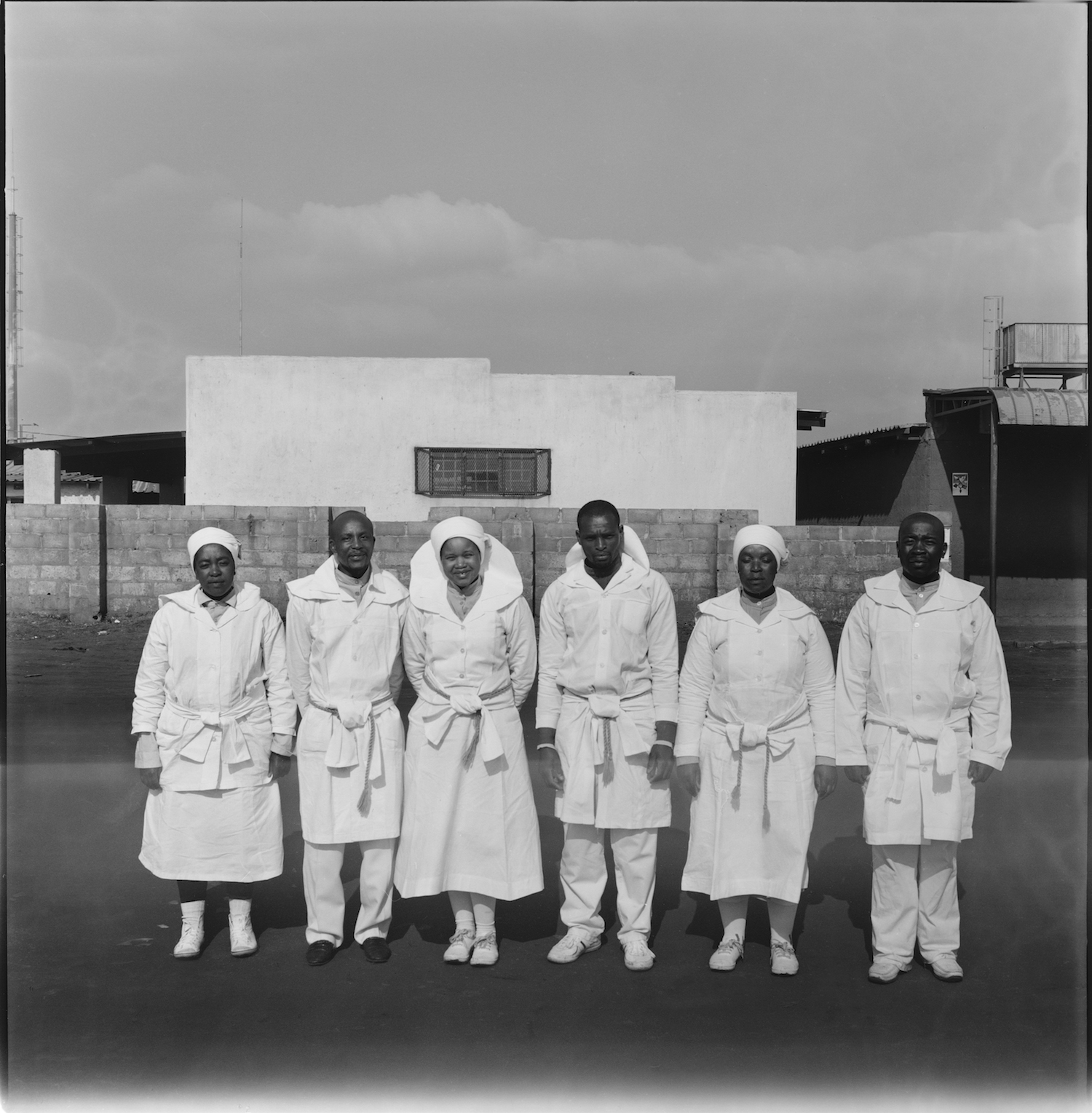

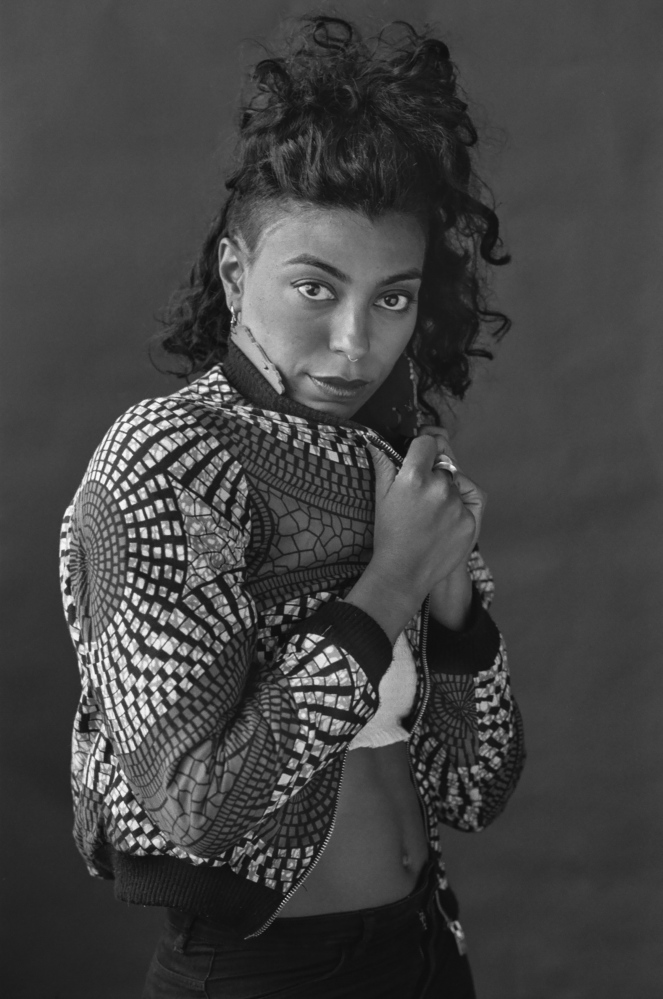

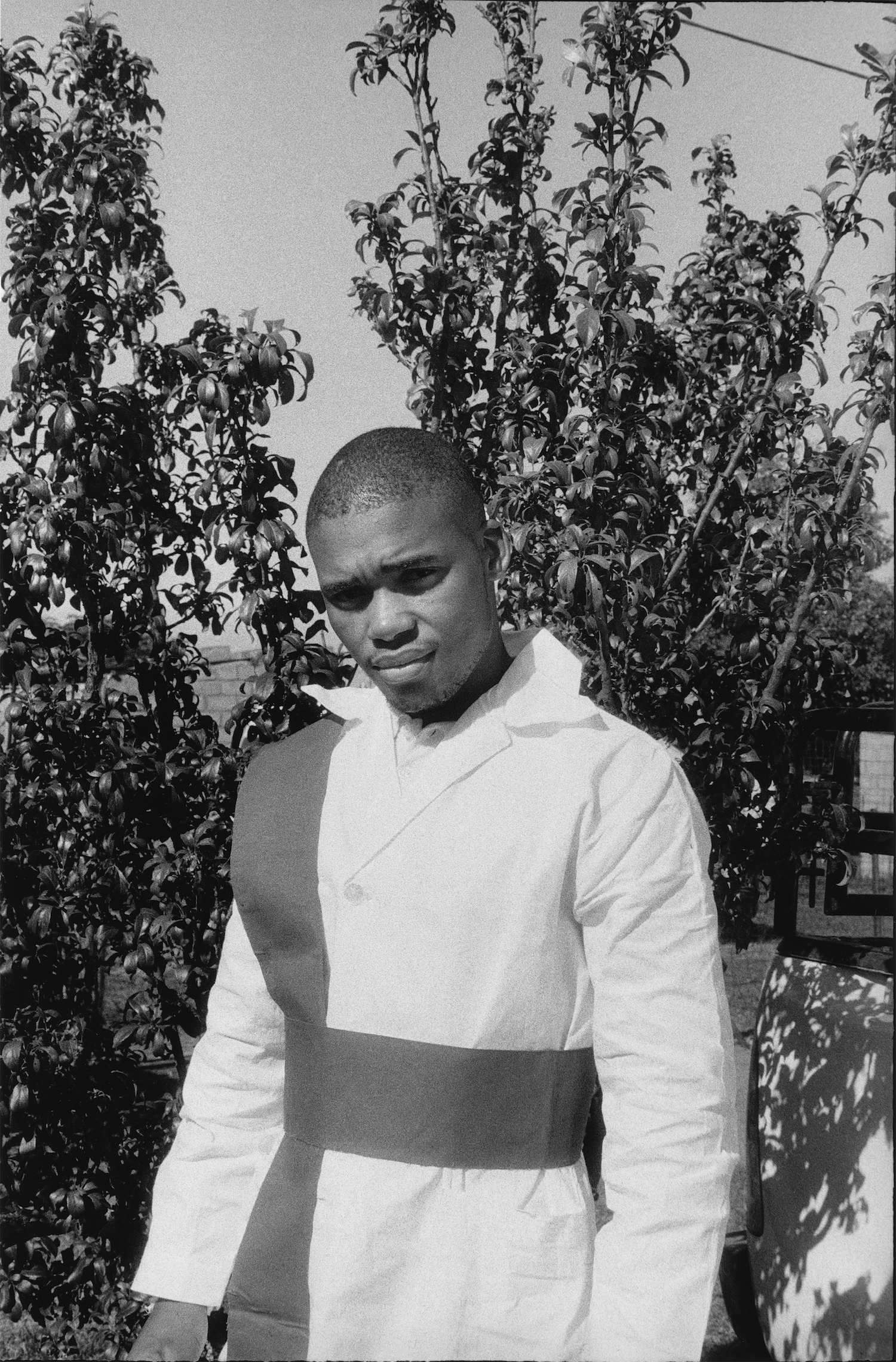

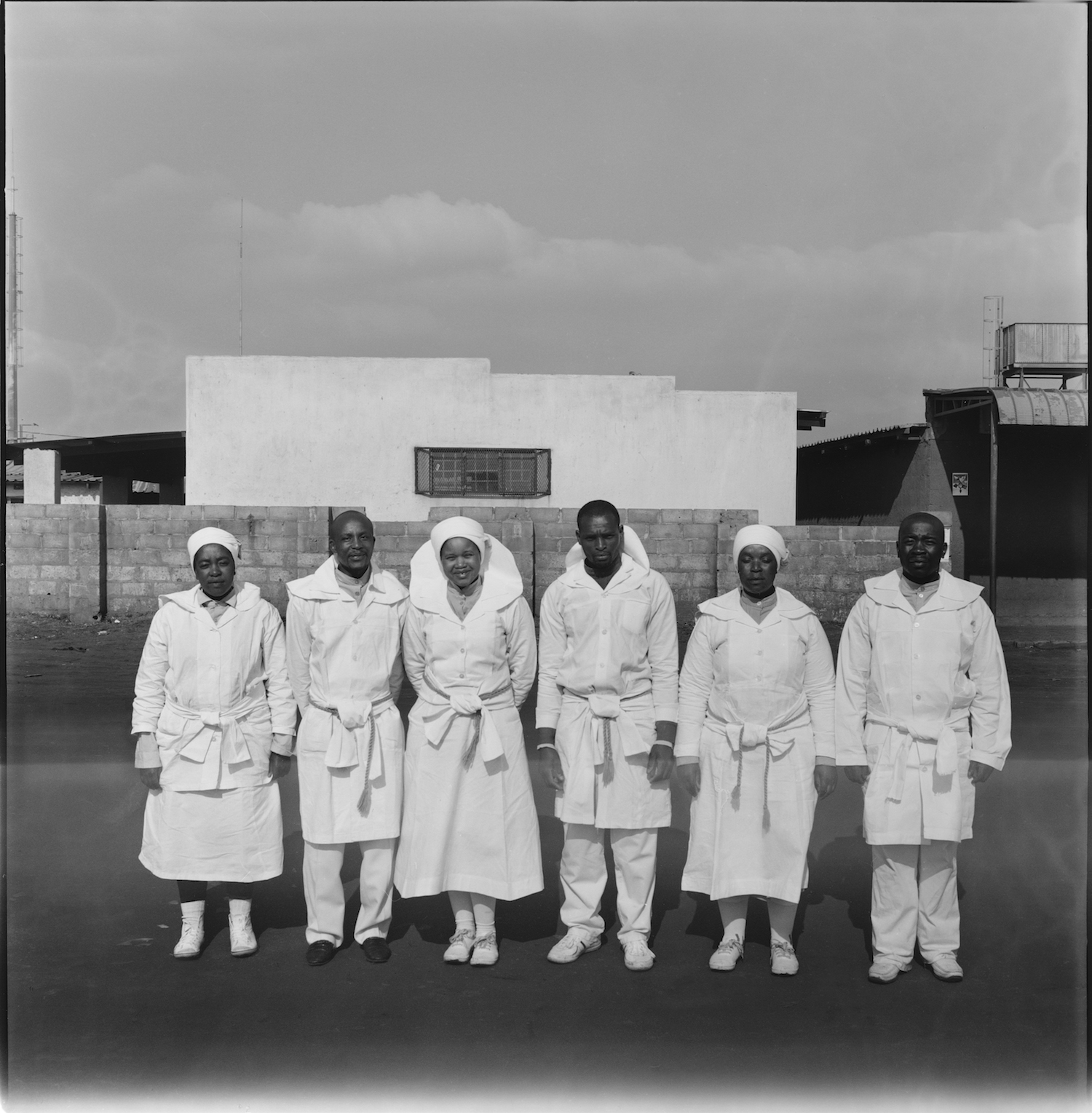

Many of my bodies of work are produced through long periods of spending time with people. For example, in my work Country Girls as well as Men Only I built up really close relationships of trust, for example, living in the all-mens’ hostel of George Goch for stretches of time. And when makingCountry Girls I spent a lot of time in the town of Ermelo where many of the pictures were taken. When I would visit Ermelo for the weekend I would stay with the same people I was taking photographs of. And with UmlindelowamaKholwa, it was a very similar process. This body of work presents the intimacy that comes through a long process of building up trust with people. And an example of this kind of intimate moment is seen in photographs like Nhlapho, Mama Thebu, Mama Ndlovu, SweetmamaKwamabundu, Fernie (2009).

Some of the photographs appear to be candid shots, while others capture posed moments. Please unpack your decisions around these choices while photographing, and how you combined these in the image selection for the show?

There are many images where you get a direct and close access to the face of the person I’m photographing. And these are important in giving people a strong sense of identity, and they are the moment when the people I’m photographing engage with me directly. But there are other moment when people forget that the photographer is there, and that you’re part of them, moving among them. These are the moments when the photographer becomes invisible, you’re no longer this guy with the camera. They know that you’re there, but they’re not worried about the camera.

Viewers become aware of the camera through effects that blot out faces, etc. Why do you think it was important for you to include such images? And how do they connect to the overall vision for the show?

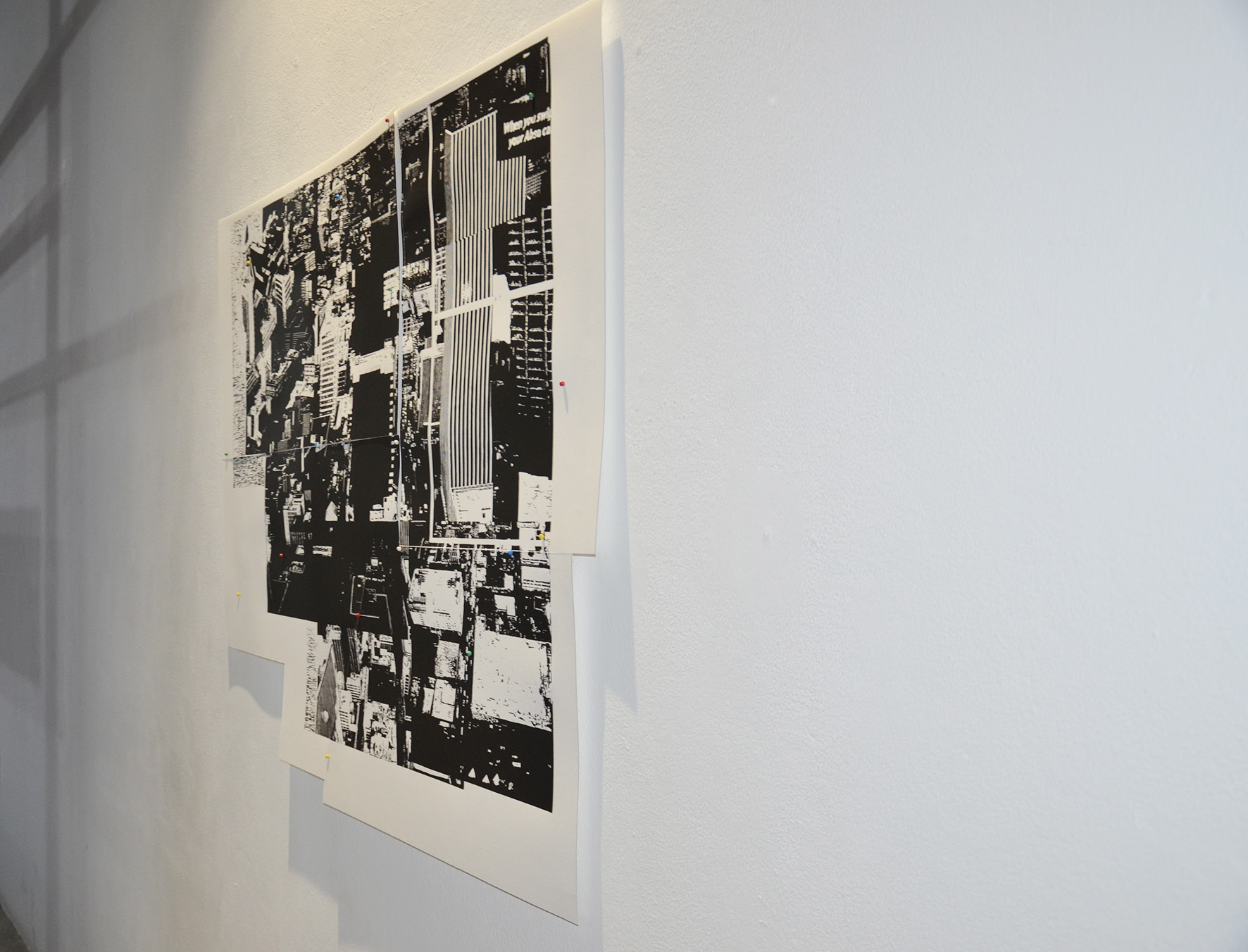

Many of these images weren’t deliberate, they happened by accident. I was processing in the darkroom and sometimes at the end of the process, you find you have that kind of image where the heads or faces aren’t visible like In Time. A Morning After Umlindelo and UmlindelowamaKholwa. Initially I overlooked these images, and didn’t include them in the body of work. But over time as I thought and questioned the meaning of this body of work, I felt that these photographs fitted into my whole way of thinking about the work. So the importance of them is that I didn’t choose them in an instant. And then at a later time I brought them in because I felt they spoke to these personal questions that I have, thinking around identity and loss of identity in the church.

How did you and Joel Cabrita come to find out about each other’s work? And how did the idea for this collaboration come to be?

In fact, Joel found out about me first, she’d known my work for a while (particularly my series Country Girls) and asked if we could meet. Her work focuses on the history of Zionism in South Africa and she was interested in collaborating with a photographer working on the same topic, but from their own different perspective. We had a coffee in Joburg and chatted, and she found out that I was also myself a Zionist, which she found very interesting, and also that I was from Driefontein, which was a very important place in the early history of Zionism in South Africa. She then sent me an article of some of her research on Zionism, which I found very important and interesting, and made me think about how a collaboration could emerge. When we grow up in Christian families, as I did, often we don’t question things. Going into the history of our church is something we hardly do. So the history that I knew of the Zion church didn’t go that deep, and I really found it important to hear more about this from Joel.

How has Kabelo Malatsie’s curatorial input added to the original presentation of the show which was seen in Cambridge?

I feel that there wasn’t really an ‘original’ presentation of the show in Cambridge and a ‘second’ one in Joburg, but rather that there have been two very different expressions of this body of work in two different places. Any show exhibited in a new space will be a very different exhibition. In Cambridge, the space where we showed the work was much smaller and it was in the context of a museum filled with ethnographic objects from around the world, including South Africa. So I felt there was this strong need for my images to really take up space and assert themselves. I didn’t want the images to die in that space. I wanted them to have a strong presence. And even at that stage, Kabelo was someone I spoke to a lot about the work. She was one of the first people to see this work when I started engaging with this topic, and really she has been involved in the process from the beginning. In fact, our long-term working relationship goes beyond this project, and beyond this body of work. Our discussions over a long period of time have impacted my ideas.

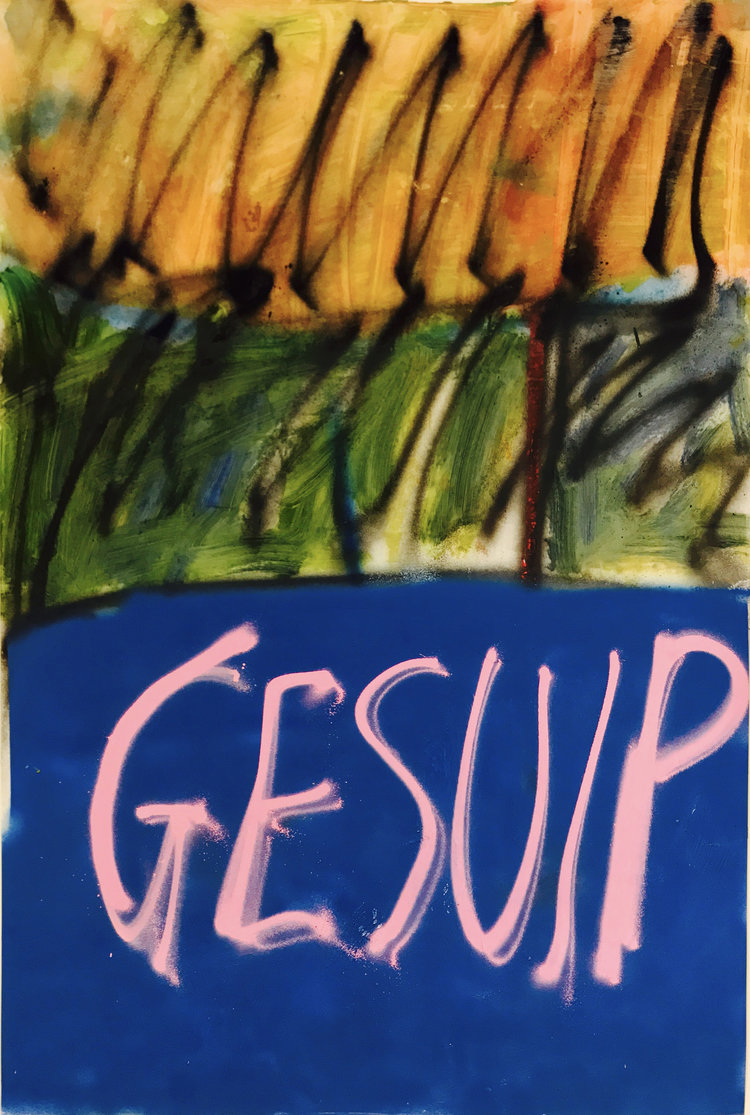

Why did you feel the need to rename the exhibition when bringing it to WAM?

The title of this exhibition is something that I’ve thought about and questioned over a long period of time. Initially it was going to be called ‘Born Again’, and then ‘Amakholwa’, and then ‘Kholwa’ (which it was in Cambridge), and finally ‘UmlindelowamaKholwa’, as it is in WAM. Bringing this work home to South Africa I felt I needed to emphasize the importance of landscape in the South African countryside (something which many of the images portray). And when I think about land, then I also think about the process of waiting for land, and the way in which many South Africans are still waiting for the land to return to them. So ukulinda, or umlindelo, are very important ideas here. And umlindelo, or the night vigil, is one of the most important moments for Zionist communities. During this process of waiting together throughout the night and praying together we find that new relationships and new families are created. It’s a time when community is forged through the experience of waiting together.

Why do you think that WAM offers the best space for this project to be presented?

It really fits because the work has moved from a university museum in Cambridge (The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) to a university museum in Johannesburg, at WAM. I find universities to be spaces of critical thinking and questioning, so it felt right to have this kind of work exhibited here. And Joel is an academic and works at a university, so it was quite natural for us to build contacts and get to know people here.

The exhibition will be at WAM until 28 October 2018.