I’ve cried over Milo milkshake at a Northam strip mall; coughed up ten rounds of mud-dust; dug the dirt from my nails; slept for fifteen hours straight; shaken the twiggy debris from my tent; plunged into nostalgia every time Wololo airs on radio; and added five new artists to my playlist. All in the aftermath of the 22nd Oppikoppi and four days in a Limpopo dust bowl.

Oppi is the largest music festival in the country, hosting over 150 acts on seven stages. It began as a small rock festival for a congregation of predominantly white, Afrikaans devotees. While these origins remain palpable in its demography, the festival’s line-up and audience has undergone kaleidoscopic diversification. Oppi’s 2016 party pastiche reflected an assortment of musical tastes, including rock, drum-and-bass, hip-hop, house, Indie, metal, and alt-RnB, with the aim of awakening audiences to new people, new ideas, and new genres.

Ours was a creative commune of clustered braai stands and deck chairs. Huddled under umbrella shade were MC’s, DJs, photographers, models, social media professionals, and entertainment entrepreneurs, all flipping meat and dispensing wet-wipes. It was a camp as committed to a shared lamb potjie and a rotating AUX cable, as it was to supporting one another’s hustle and artistry.

There were those cutting-cold nights when we were kept awake by our feet. All three pairs of socks and still our toes were never quite warm enough to go unnoticed. Those nights when an encompassing blue-pink sunset drew in a bespeckled black sky and the stars forced their way into conversation. “How did these extinguished fires, so far away, seem close enough to be plucked from their black canvas?” Those nights we crawled into our tents at 5am, encased in meat-scented smoke, clutching to any available warmth, only to be cooked out of our beds at sunrise.

Dawn was ushered in by human wolf-cries, echoing across the steaming valley. Heat poured over the skin, with an after-sting of grit and acacia thorns. We learned to cherish simple pleasures: a sip of cold water, a friend’s finger coated in lip-balm, a dust mask, a slice of flat ground. Each day we navigated from basecamp to ‘the belly’: over the danger tape; past the gazebo emanating kwaito; turn at the row of green toilets; pit stop at the Red Frog tent, where water, coffee and pancakes were offered to wayward travellers; and finally dive into the current of festival-goers, decked in ripped denim, Basotho hats, dusty moon bags and bandanas. Each group yelling ‘Oppiiii!!’ as they passed: part-greeting, part-salute, part-chant. In the heat and grime and crowd-sway, everyone looked paradoxically more beautiful. “It’s that dusty love”, I was told. The lovely young, effervescent in bush-wear couture. Oppi was a simmering incubator — of sound, and creativity, and disparate bodies colliding.

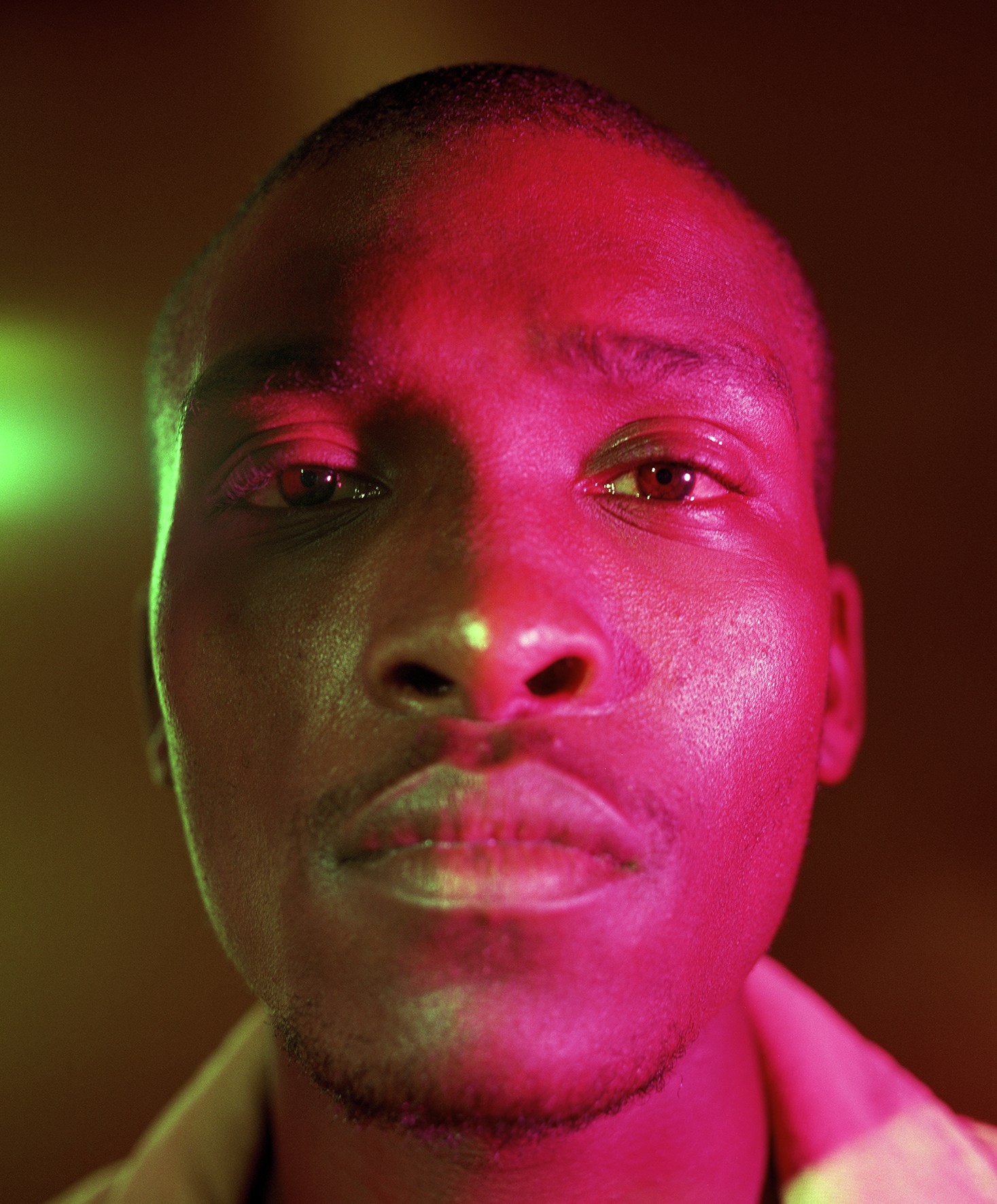

Where the day was about scarcity and longing for a flush toilet, the night erupted in excess. The most sophisticated technologies of sound and light extended laser beams and synthesisers from the peak of the ‘koppie’ over the 20, 000 campers below. At the festival’s pinnacle, pegged atop the hill, was the Red Bull stage, where green light darted up the trees like florescent lizards. The three neon triangles above the DJ decks reverberated bass over the natural amphitheatre and into the bellies of the audience. Here, the dance floor was a slope of sand and rock. We clutched onto strangers’ bodies for support and offered hands to pull others out the pit.

Over the course of the weekend, some of the country’s best DJs shook Red Bull ground, kicking up dust from the decks. Newcomer Buli spun melody and groove into a perfectly ambient set, lifting his audience from their rocky footholds into a cool sway. Duhn Kidda’s genre contortionism had us dipping from Ja Rule, into new house, and back to the Noughties. Then there was the moment Diloxclusiv dropped Gqom on an Oppi stage. Unapologetic and dripping ostentatiousness, he spliced Durban dance music with struggle songs, while the crowd spewed whistles and ‘woza!’ An impromptu performance by DJ PH had us fast forgetting about Nasty C’s last-minute cancellation. You know that stomach-shaking ecstasy you feel when your song is about to drop? Now imagine it every twenty seconds, your arms stretched out for more. He’s the DJ who plays “37 songs in one”. We pulled him back for an encore set.

Magic mixology was interspersed with fire-spitting live acts. Saturday night belonged to 21-year-old North-London lyricists, Little Simz, who entranced her audience with grime-stained confessionals, carried by bass-heavy production. While hip-hop, RnB and dance music have often been synonymous the Red Bull stage, there have been increasing attempts to diversify stage acts and prompt eclectic discovery. MC’s Riky Rick and Khuli Chana performed on Main and Skelm stages respectively. Petit Noir’s enrapturing Main Stage performance rippled into evening conversation. We celebrated his sound while stoking hot coals and climbing into our night jackets. On Sunday, DJ Ready D took to Main Stage to receive the festival’s Heavyweight Champion Award. His banging tribute performance set the crowd and Twitter alight, featuring guest artists ‘direk van die Kaap af’: Prophets of the City (POC) inserting (P)eople (O)f (C)olour into the festival’s Afrikaans cultural production. “Sit jou hande op, terwyl die beat klop”. Also on Sunday, 2Lee Stark, backed by Boombapbase, shut down a sweltering Skelm Stage. His perfectly tailored set and electric stage presence had me feeling like this was an artist, pre-detonation, about to explode on the local hip-hop scene.

It’s days since I returned from the Oppi dustbowl. I’ve submerged myself in sanitising bathtubs and sunk into the nostalgia of the Unsea. Some of my clothes still smell of a dusty Northam farm, where we surrendered to “the cusp of this here whatever time” and “prayed in a language that would outlive us” — music.