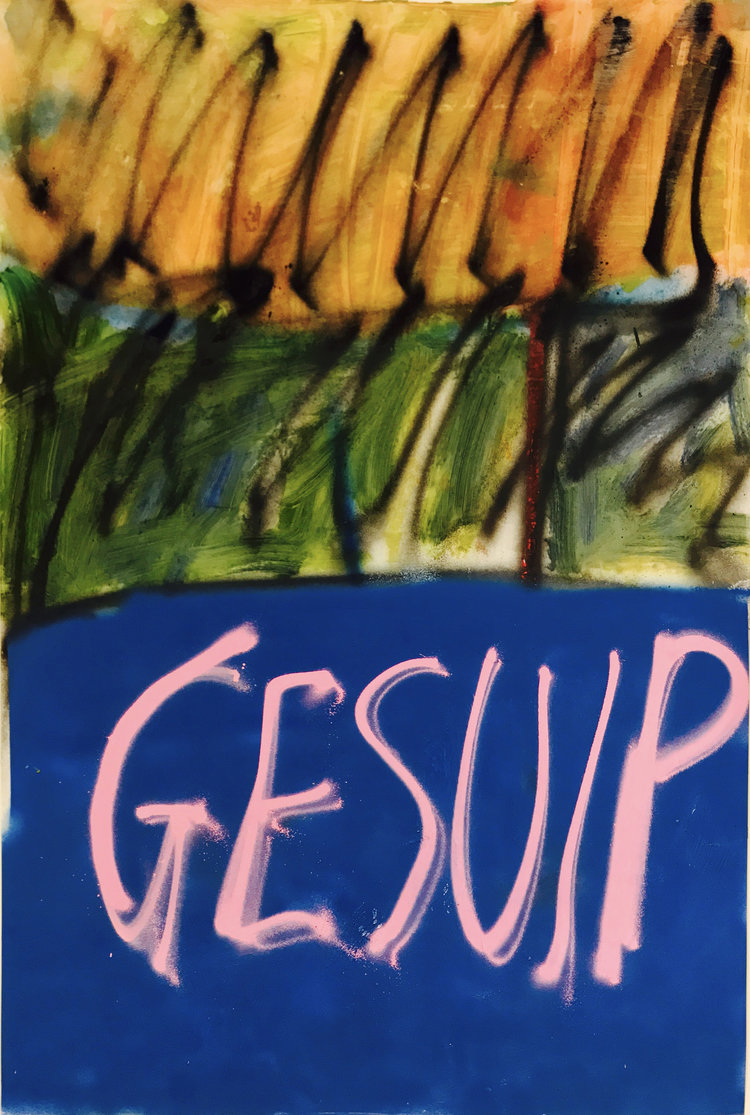

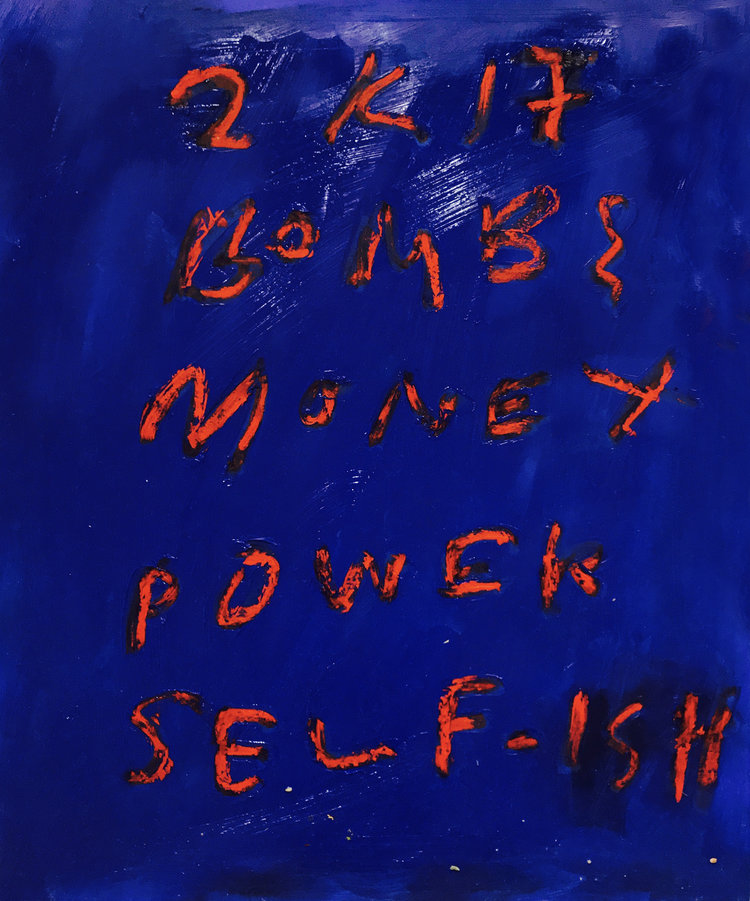

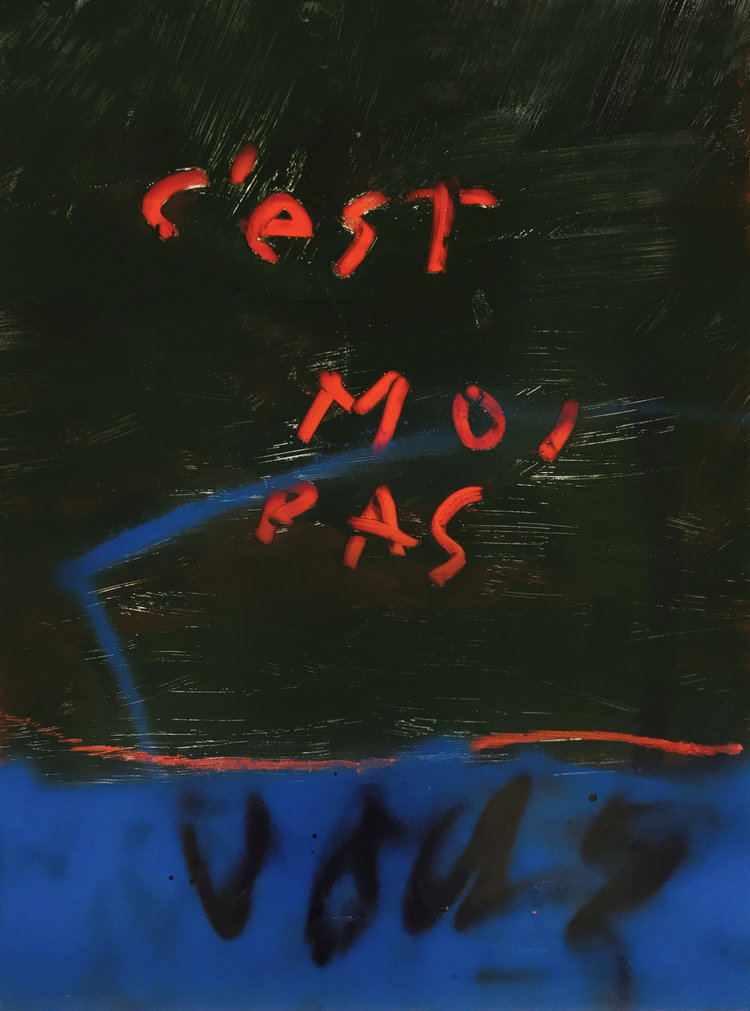

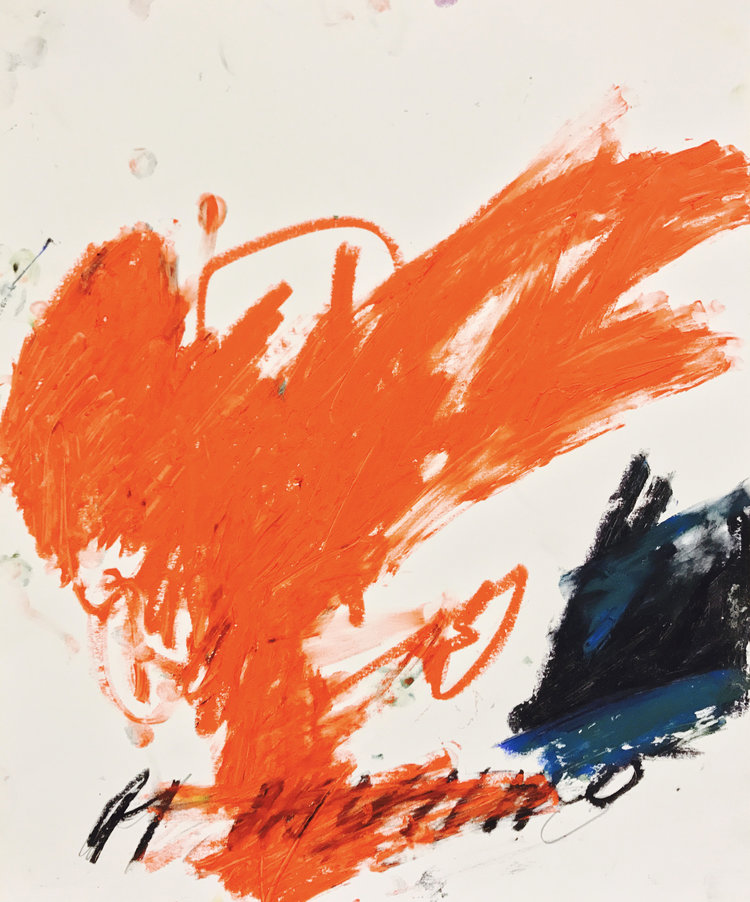

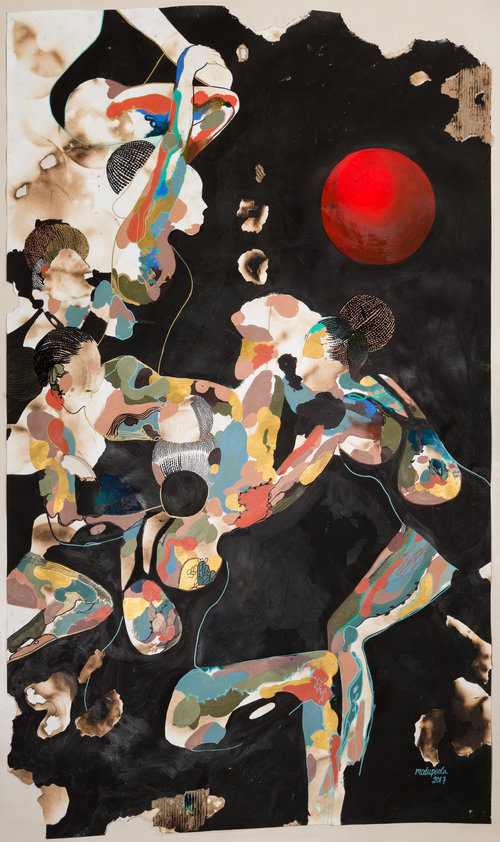

I just love it when Jazz and print medium collide! One example of such can be found in Mongezi Ncaphayi’s latest body of work whose “distinctively abstract visual vocabulary” (SMAC, 2016) brings these two mediums together. His works are minimalist in form. They’re representational of the sounds found in one’s own recounts of memorable score.

The quiet journey to artistic discovery

Mongezi has always been an artist of sort. Growing up, he would be sketching under the guidance of his uncle who also an artist. It was under guidance of such older mentors in the township of Wattville in Benoni that he would get to hone his craft. At high school level he sadly stopped sketching.

He completed his primary education and went to study engineering. It would be by chance that he met a certain guy at the public library. He was giving art lessons to small kids. He allowed Mongezi to join in the lessons even though he would be the oldest one there. He himself didn’t mind and he would get to reconnect with his love of art. It would be this same teacher that would suggest to Mongezi that he study art at what was then Benoni Technikon.

“I just dropped and went. Growing up I never saw myself as working anywhere. After school and during school holidays I would instead find stuff to do. I soon felt that with engineering that I’m done!” He had his disagreements with his parents but art was his calling. He’d been re-infected with the creative bug and found his vocation. He would complete his studies then with a Diploma in Art and Design.

Soon after graduating in 2012 instructors from the Boston Museum of Fine arts from the United States would like his works and invite him to attend their school. They arranged for him to attend the Museum school as an exchange student and have his stay extended to 2 semesters. He got his certification in advanced printmaking. From 2014 he would exhibit internationally. Some of these exhibition included the South African Voices which showed at the Washington Print makers Gallery in the US and Alternative Spaces, Plateforme on Time in Paris France (SMAC, 2016).

Progressions of sound as an Artist

His style has made a drastic change to its current abstraction form. He previous works were created by collecting discarding working tools. “Benoni was a mining town. So much of my previous work was focused on migration, history and migrant workers. It was about looking at my father and those living in the township”. These works were graphic landscapes juxtaposed against the old discarded forms.

It was through the workshop he attended at the Boston Museum that Mongezi would decide to focus solely on Abstract works. He had been doing abstract works earlier in his career but had not shown them professionally. When he enrolled at the Museum school it was his abstract works that caught the interest of his instructors as well as his own interest. “I was exposed to so much abstract work overseas. There was no point in going somewhere only to come back and do the same. I wanted to do something new. I wanted to adapt, take influence from the world around and incorporate all of it into my work”.

The Art of Jazz and the Jazz in Art

Mongezi grew up in a house of all jazz. There would never be any R n B CDs or LPs. It was always jazz. His father used to take him to jazz clubs and festivals. Benoni has a strong jazz scene. Many of his friends play jazz and he also aspires to play. “My works are the same thing, Jazz! Listening to music it’s what I’m doing. Playing around with sound but in print form. I hear music in terms of colours and shape.”

He has always been interested in movement, previously as migration but now in art. “It’s all about movement and where you find yourself in it as such. I’ve always had an idea to incorporate music and art. The current exhibition is not complete as I am still building. It’s there but it’s not there. There is so much that I want to do. There is so much coming.”

“I’m a visual artist but must also incorporate music into the art. This also started with me making my abstract art. Having an idea that music, jazz, visuals all go together. I used to listen to one Record, one song and play it over and over again. I would really listen to what it does to me spiritually. Not in terms of the artists message or musicians vision but in terms of what I feel. That’s how the music works for me.”

The Gallery space is the place

His latest exhibition entitled Journey to the one would be set up in response to the formality of his previous presentations. When he last exhibited at the SMAC Gallery his show had been characteristically formal. “My work is part of my re-introduction to that space. I wanted to do a different show in terms of style and unique direction. Basically I just wanted to play around, more free flowing space. These freedom for Mongezi becomes his safe space, “it’s my studio space”.

For Mongezi where is work space is a sort of temple where he can divulge himself into the music and his works. This area of the exhibition offers a glimpse into who the artists is that has been making these works.

“To be free and roam, to be yourself. Keep quiet, the silence, this where you get to feel. Things that make sense to me, they puzzle me. The words are interesting but also puzzling”.

The gallery is transformed into the visual representation of the artist’s creative process. In the front of the gallery with framed works, large prints, all complete.

At the back is a cascade of rough sketches, LP covers and quotes pinned on the walls.

The title of his current exhibition refers to the LP by Pharaoh Sanders ‘Journey to the one’. “Listening to the music blows me away. It’s subtle but also chaotic, but also free. If you understand his music you don’t need to share the same ideas with artists. It can happen simply at the level of expression. Some things I read and feel like this touches me. Feel connected. I do my own interpretations.”

Yet for Mongezi his interpretation of the music does not rely on the sheet music. For him it doesn’t make sense to do so.

“You can do it but it’s about how you use it. I want to do something new, something different. It’s about how the music makes me feel. When music plays I try to visualize it. When it’s a note or phrase I tend to locate it as shapes and patterns. Thats my interpretation.”

Mongezi’ s works are the extraction from intangible to tactile form. His works represent the progress of sound as it arranges itself into the minds of the audience. The sound is improvisational jazz, from its chaotic rhythms and uncontrollable beats, the print becomes baptized in a layer of water colour. From the chaos comes sense as the mind begins to take over. We begin to see the thick lines colonise through noise but what mind can really own the music. We can only be satisfied with that moment in time where we felt as one with its melody.

Catch Mongezi’s exhibition Journey to the One at the SMAC gallery which is now showing.