pictorial nerve is an ongoing poster series conceived and published by offsetculture.art. The series connects contemporary art, design, illustration and other visual manifestations of culture. I had a chat with offsetculture.art co-founder Lara Koseff to find out more about the recently launched first iteration of this series.

Please share more about offsetculture.art?

offsetculture.art is a website that I established with a friend of mine, Ricardo da Silva, offering multiples and printed matter, with a focus on collaboration and featuring artists who work independently. We noted how print and digital worlds have experienced a really effective coalescence in recent years. Multiples are often accessible, easy to disseminate, and still maintain an element of value, which segues nicely with how people tend to buy within a certain price range online. However, locally there appeared to be limited established online opportunities for artists who are starting out, or work independently, outside of the gallery arena – and it’s these artists who I felt could really benefit from such a platform. When we came together to establish the website, Ricardo, who has a finance and computer science background, was coming from the angle of a young collector frustrated by what he could find online. I had been working in the commercial gallery world for almost a decade, and observed how both artists and young collectors felt equally alienated from the traditional art circuit. I felt that South Africa was an even more exaggerated version of the art world at large, with a massive disparity, lack of opportunity, yet enormous talent. I also saw how, interestingly, young artists were starting to try and build their own systems and networks, rather than struggling to find a place within exclusionary existing ones, and found this really compelling. A lot of these alternative initiatives manifest in printed form, editions, zines, artist books, posters, and the dissemination of them is starting to happen online, primarily through social media. We were particularly excited to engage with collectives such as Danger Gevaar Ingozi and Title in Transgression, who are functioning independently in vital ways and shifting the cultural landscape.

How does this ongoing poster series fit into the aims and ambitions of offsetculture.art?

How does this ongoing poster series fit into the aims and ambitions of offsetculture.art?

It was a meeting of minds between myself and Ricardo, who wanted to focus on creatives coming from a range of perspectives – illustrators, designers, street artists – and I wanted to find a way to bring together image, text and ideas in a hybrid format of a portfolio, a zine, an artist book and an artwork. It’s offering a small curated exploration of diverse talent, and the anatomy of it is simple and pretty open to future expansion or alteration. In a broader sense, it taps into our drive for democratisation, and I’m especially excited about the fact that all of these artists are working outside of traditional spheres, making engaging work, and we’re simply providing another platform for people to know about and access it. Coming from a curatorial background, one of the challenges of working in digital space is how you bring works together in conversation with one another – it’s quite a bit more fragmented and prone to distraction than a physical space – and I was longing to delve into that and explore various solutions to an interesting dilemma. I’m also really interested in exploring how this material can exist within and outside traditional art spaces, both physical and digital.

Why were posters chosen for the series?

I think the key idea behind posters was creating accessibly, but also elements of what they represent symbolically and ideologically. Posters date back centuries, are associated with a variety of fields and contexts, from advertising to propaganda, but also became a really important tool of both creative and ideological expression in the Global South, especially in the 20th century. Poster portfolios in particular are really fascinating to me in that they bring together so much in one small slip case, they can expand and contract, and can in a sense be curated and re-curated in different ways. It’s like holding the components of an exhibition in your hand.

Share with our readers how you came to the name ‘pictorial nerve’ for the series?

In a way I felt that posters are very much associated with the pictorial, but I love how this term has become so very broad and tricky. To illustrate something does not merely mean representing it, and there exists a playfulness in terms of the constructed nature of images. So it was a play on “optic nerve”, and what we see and perceive, and how we depict that. I also loved the double meaning of “nerve”, and that apart from the transmitter of physical feeling, it also points to boldness or audacity. This is important part of art making for me – I think that the best artists have some form of chutzpah.

Please unpack the importance of archiving within a moment in time (particularly visual archiving) as pictorial nerve does?

Again, I feel that there is an important and beautiful nexus between image and text, and that, especially in contemporary art, this is the key component of archiving. I hope that in future series we can work with writers and artists collaboratively, and generate new writing by diverse voices, which I think contributes invaluably to archiving a moment. I do think that the portfolio element offers archival possibility, especially in an exploration of a zeitgeist or a like-minded or comparable ethos. In the build up to this I had come across various historical portfolios, for example Matthew Krouse, a friend, consigned to us a collection of colour posters celebrating both Mozambique’s independence, and the 1st of May Workers day, and Steven Sack revealed to me a portfolio by Taller de Gráfica Popular, an artist’s print collective founded in Mexico in the 1930s, who used art to aid social revolution. These to me are incredible anthologies of collective thoughts and ideas, and I became compelled to try explore this in a contemporary sense with divergent creatives, but not focused on a particular political movement or ideology. On the flip side, having done my MA in heritage studies, I believe that a core component of archiving is having a physical space (as well as a digital one), a “home” or a “safe” space for these materials to live. So obviously we’re not tracking or providing that space, but providing the structure and possibility to continue generating new material.

How did you select the artists, designers and illustrators who are part of the first iteration of the series?

Many of the artists were approached based on a conversation that I had with Ciara Moore, who is a brilliant graphic designer who I had worked with. She was interested in making new prints with us, and I put forward this idea to her of a portfolio that doesn’t necessarily distinguish between artists, designers and creatives, and embraces the confluence of various disciplines and worlds. She came back with some suggestions of artists who she was excited about who she follows on Instagram primarily, and I also explored a bit online and came across artists who I felt were traversing various contexts. I had also been speaking to certain artists about the format of posters, especially Malebona Maphutse, who explores the language of street flyers and popular wisdom in her work. She in turn put me in touch with designers and illustrators who she respected including Musonda Kabwe and Kgabo Mametja.

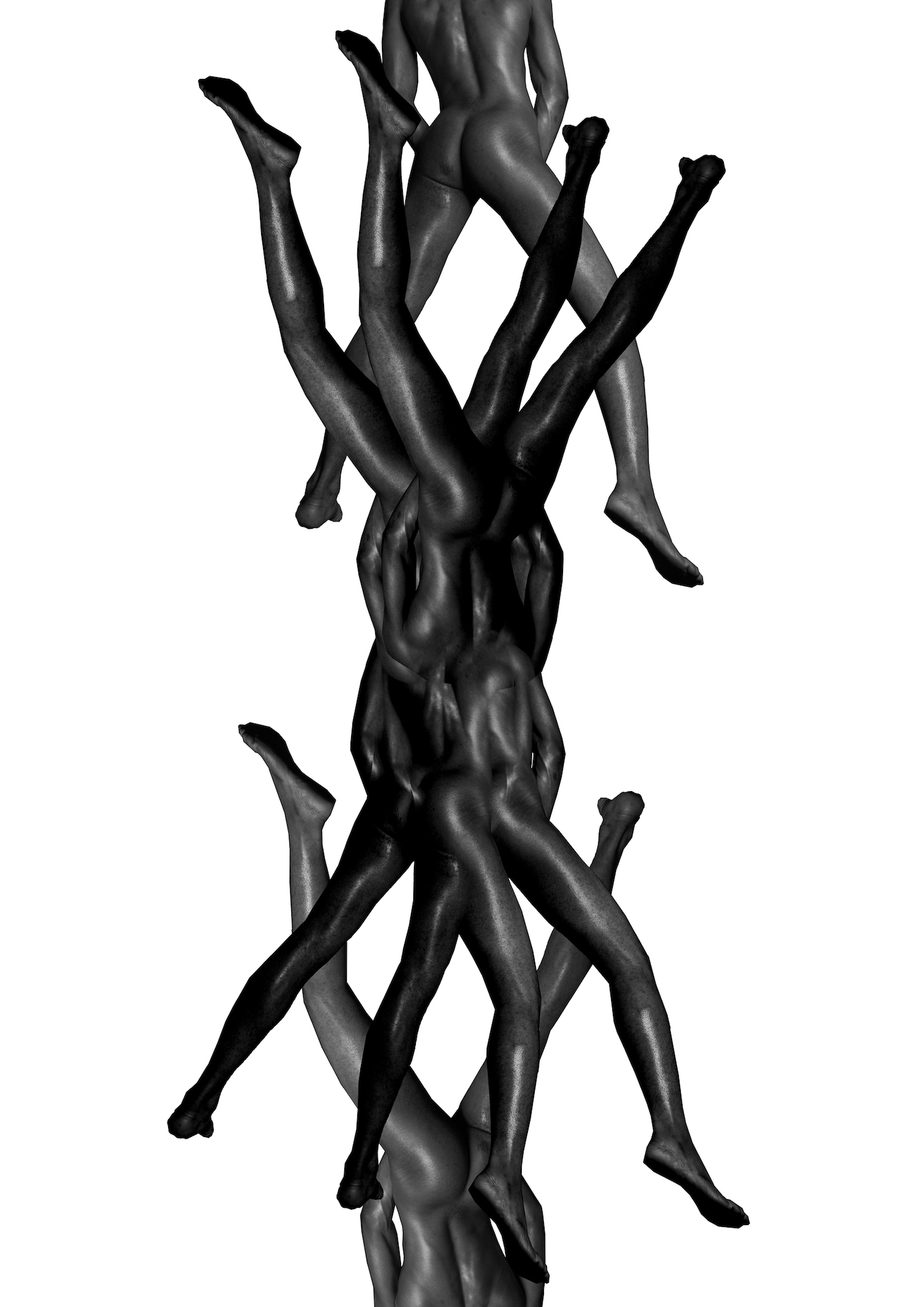

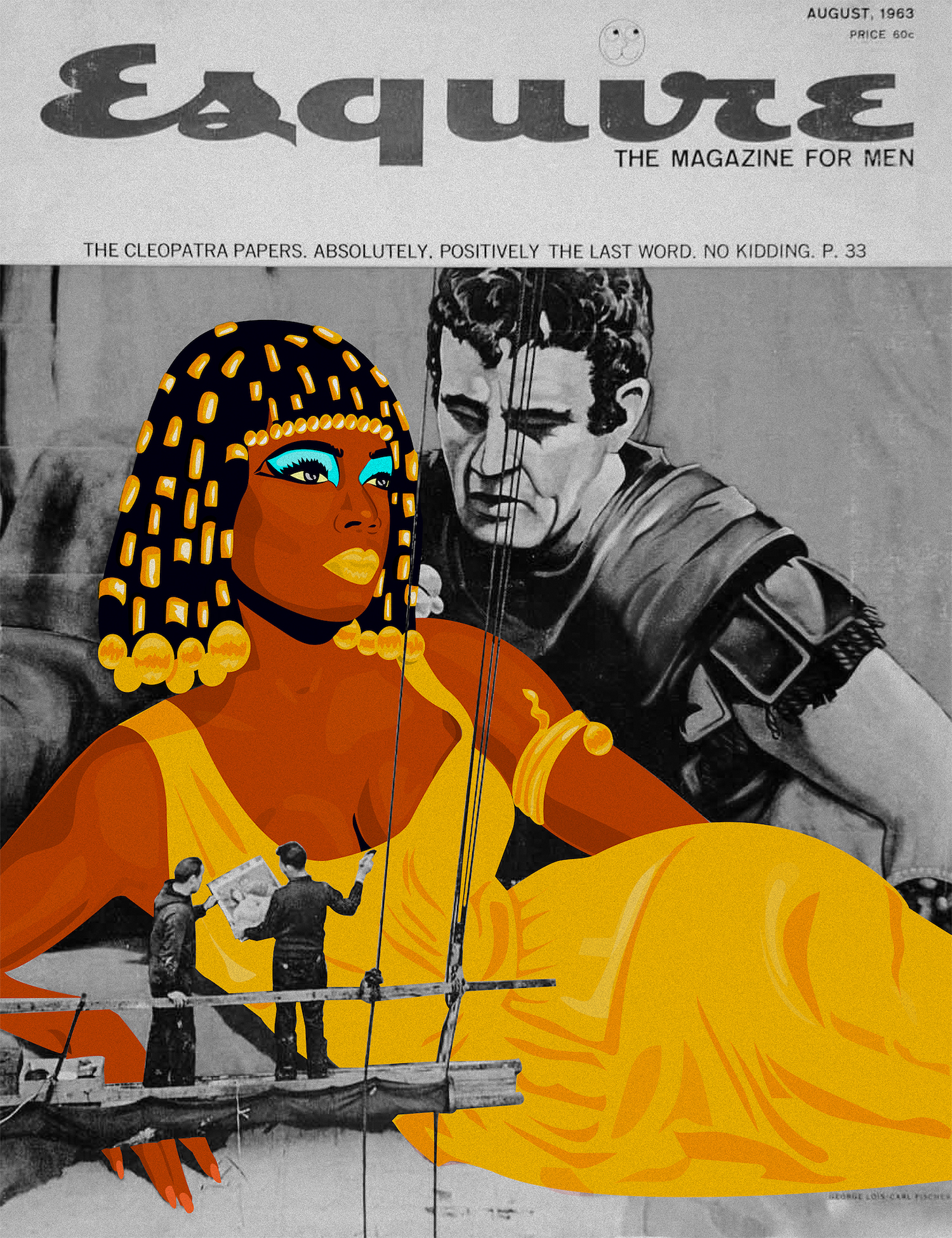

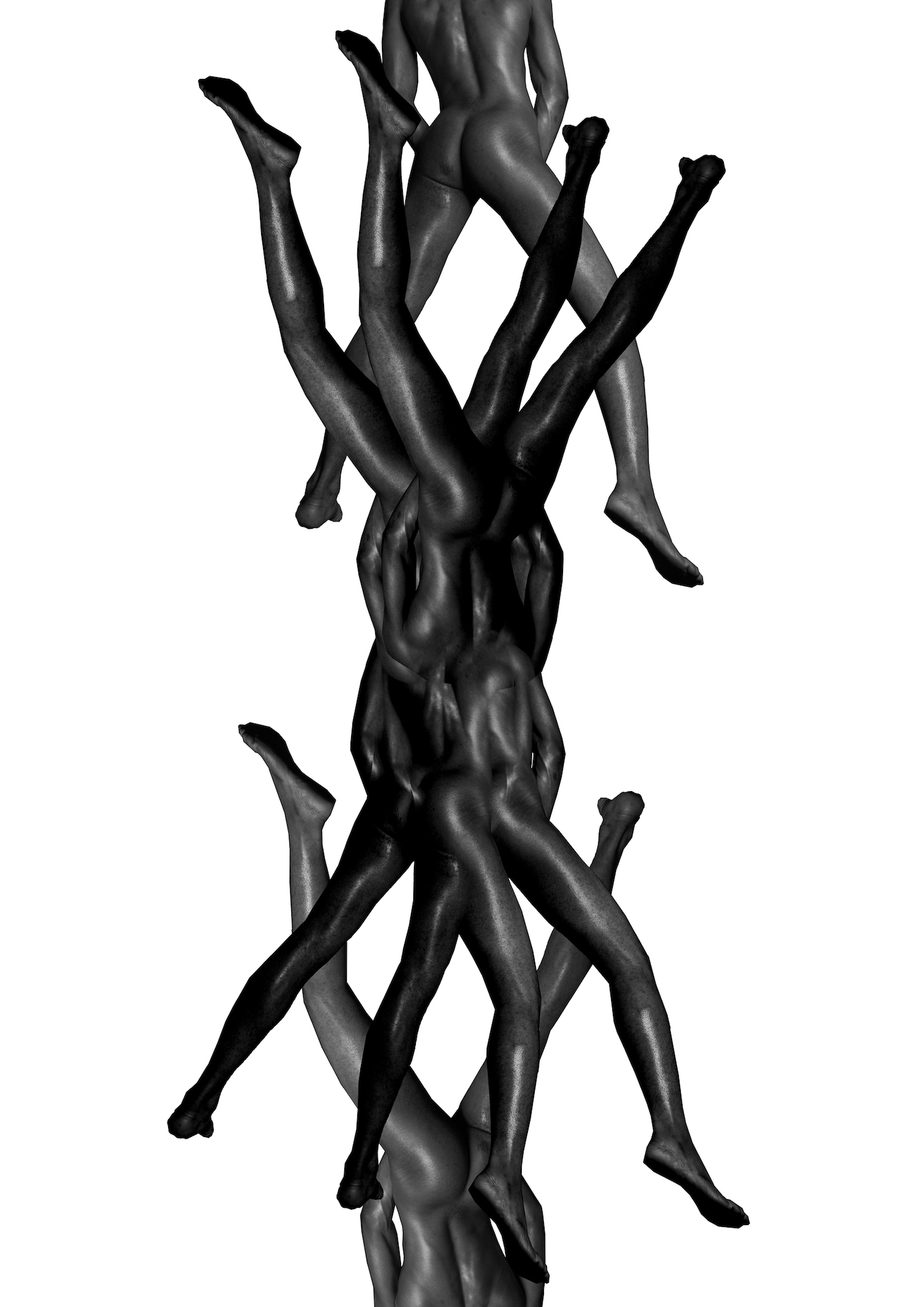

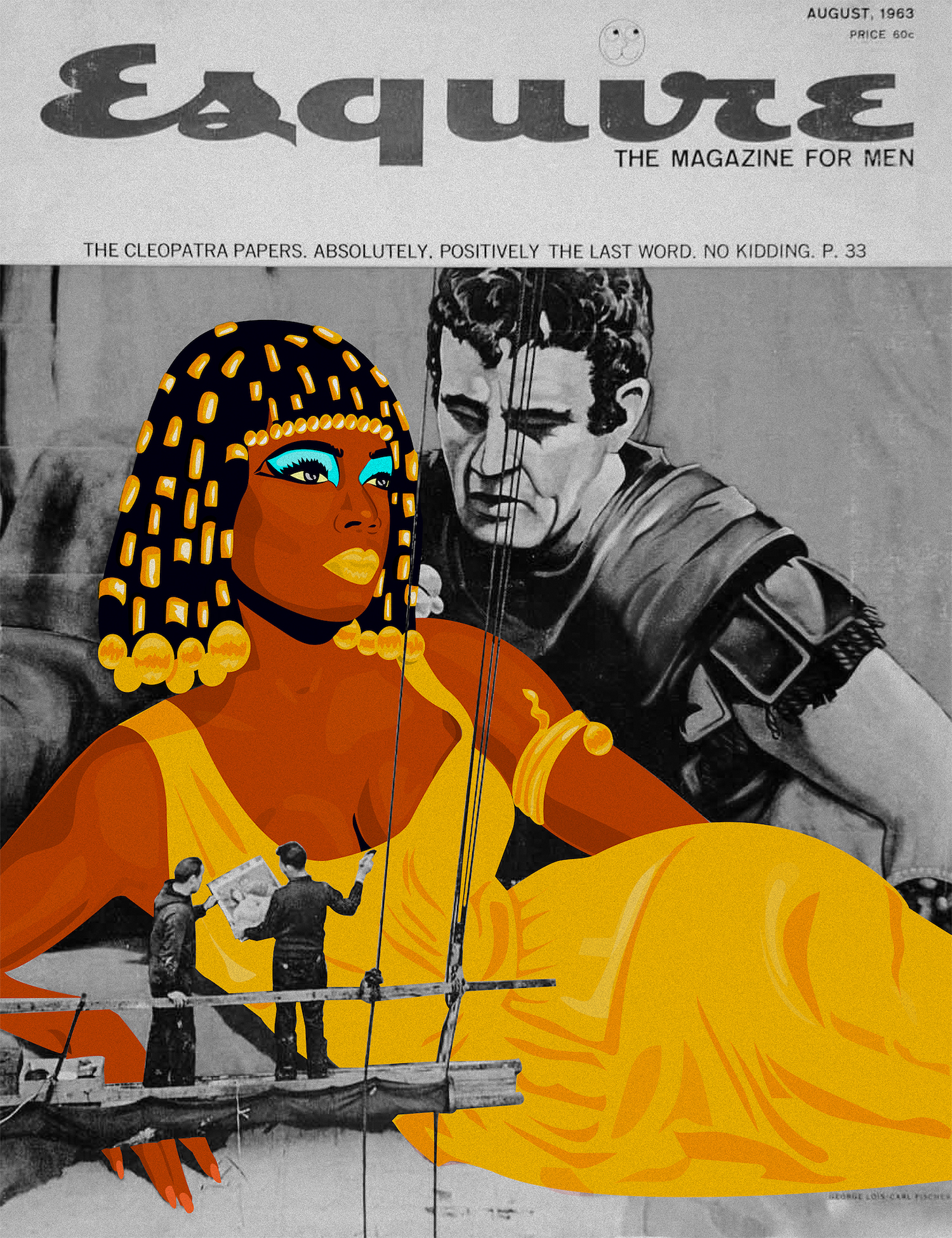

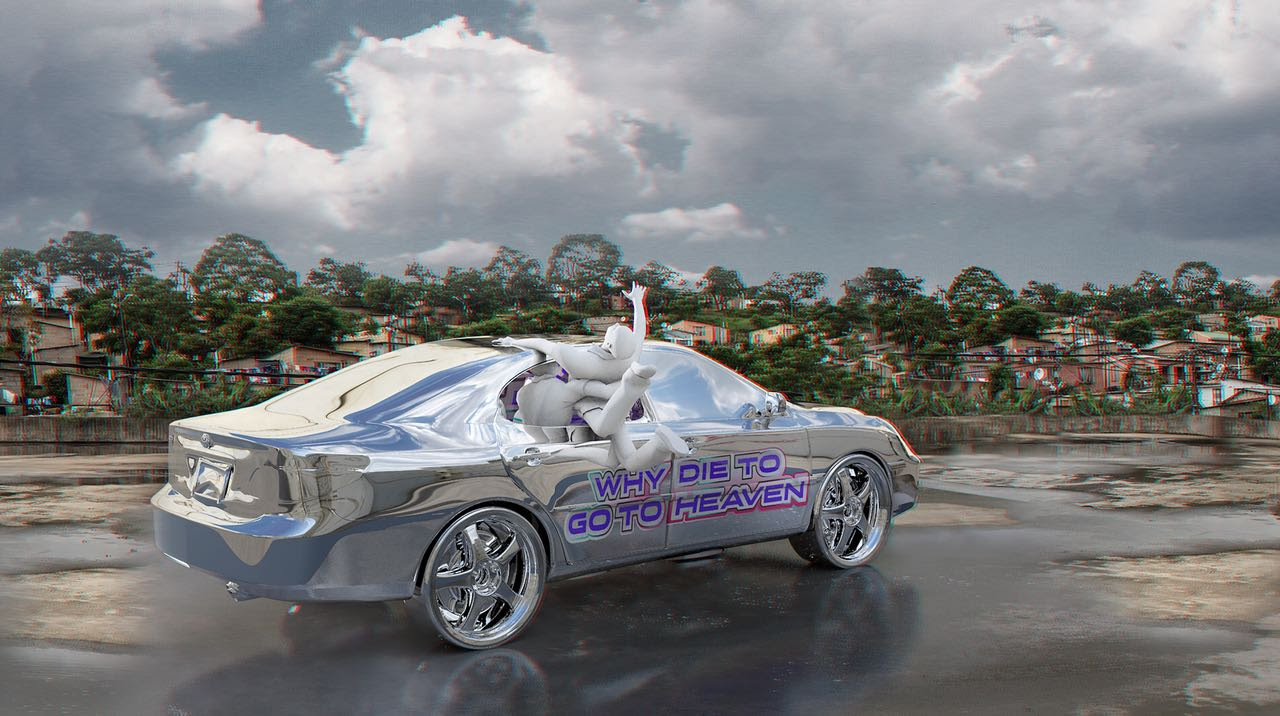

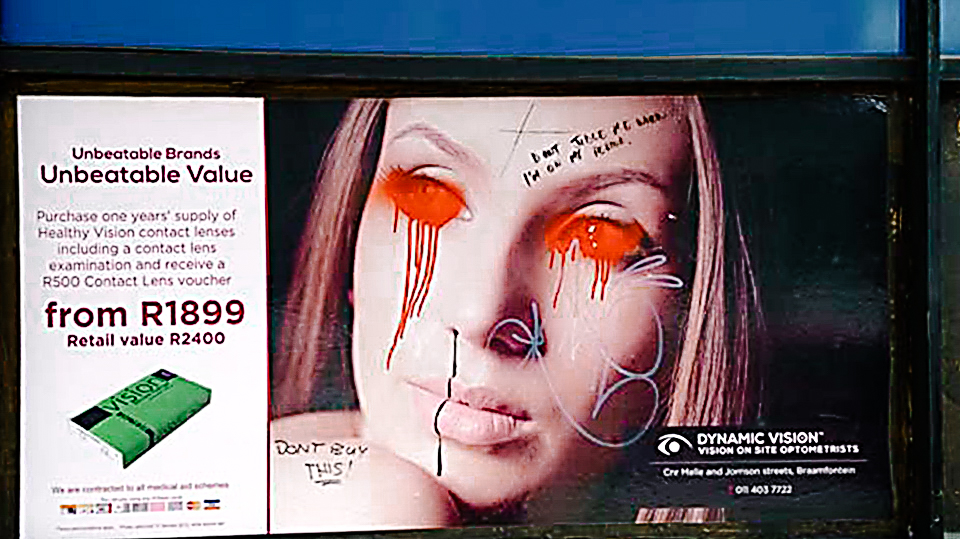

Growing up in the 1980s and ‘90s, I became obsessed with was loosely known as The Pictures Generation; appropriation and montage all pointing to the way in which images are constructed and reconstructed. Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Lorna Simpson – these names were all mainly foreign to the artists we landed up approaching, which I thought made the parallels even more interesting. I think that the mechanism of appropriation and reconstruction perhaps becomes easier in the digital age, but at the same time more challenging to make something truly powerful. What interested me in these artists was the unexpected diversity of their references, and the lateral way in which they used the digital medium to reformat techniques and ideas. Luca Boni is a digital painter influenced by Italian masters; Lunga Ntila uses collage to digitally reclaim control of identities forced into fragmentation, influenced by the male-dominated movements of cubism and post-expressionism but also radical feminism; Octavia Roodt employs comic strips to tell Namibian Voortrekker myths; r1. combines the language of the street with Mondrain colours and values.

What does offsetculture.art envision for the series?

I hope that we can do at least one portfolio a year, and also play with different mediums, and go in unexpected directions. I’m especially excited to potentially work more extensively in screen-printing and the simplicity, challenges but also surprises it can offer. As mentioned, I also hope to work with a variety of writers, and bring in essays and interview-based text.

Who do you see as the audience for this work?

I think that one of our key initiatives is to emphasise that anyone can be a collector, or an appreciator of art, and with this in mind we’re not targeting a particular audience, but hope to appeal to the culturally conversant public, and people from completely other spheres of interest equally. But something that is important to both myself and Ricardo is that we certainly nurture, but not only focus on a local audience. Participating in the Tijuana Print Fair in Sao Paulo is hopefully the beginning of a quest to embrace the international nature of contemporary art, specifically focussing on the Global South. I feel that this can not only engender a more dynamic conversation, but also opens up significant opportunities for young and independent artists.

Share more about you spending time in Brazil for the Bienal?

I was invited some time ago by a Brazilian friend of mine, Paula Borghi, to curate a video programme, and we’re collaborating with Thelma Vilas Boas who runs an interesting cultural space called Lanchonete<>Lanchonete in Rio de Janeiro on the 1st of September. We’re actually featuring videos by Malebona Maphutse and Lunga Ntila, who are included in the portfolio, as well as several other artists including Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Nastio Mosquito, Reza Farkhondeh & Ghada Amer, amongst others. We had always planned it to happen around the time of the Sao Paulo Bienal, so I’ll certainly be going through to that as well.

How can people get access to pictorial nerve?

We’ll be launching it online in September – the portfolio and individual posters will all be available from our website – and we’ll also be doing a series of physical events in various parts of Johannesburg, specifically as part of the Keyes Art Mile Art and Design Saturday in October, which will be focused on editions and alternative platforms and collectives.

Anything else you would like to mention about offsetculture.art or pictorial nerve?

We’re excited about the potential for metamorphosis in the contemporary art sphere, especially what’s possible through collaboration, and being resourceful. I’m hoping to explore more of that in the coming years, and that we can help motivate for a more connected art community.

How does this ongoing poster series fit into the aims and ambitions of offsetculture.art?

How does this ongoing poster series fit into the aims and ambitions of offsetculture.art?

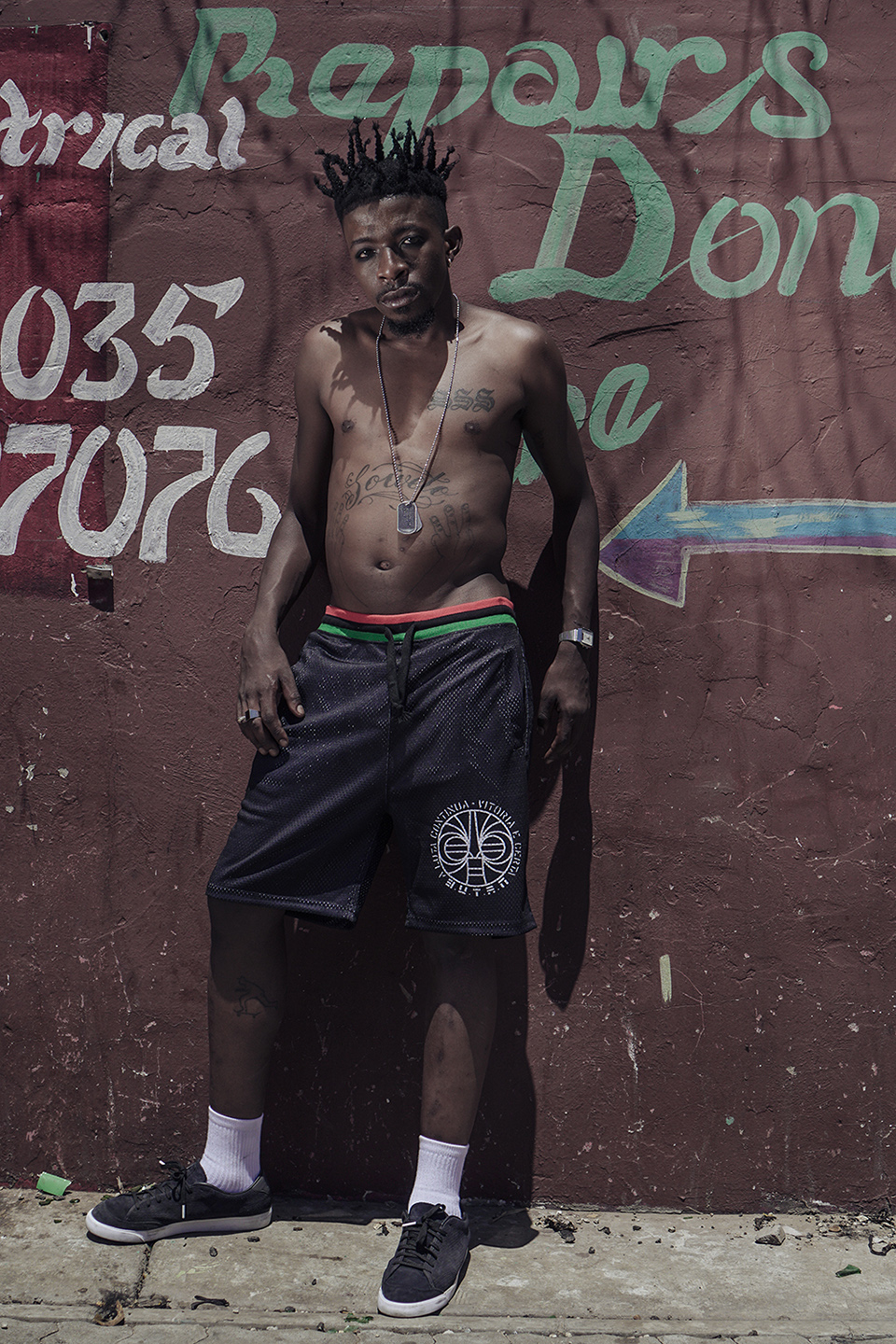

“By incorporating a powerful struggle slogan into our clothes I by no means pretend that we are immediately having a powerful impact on people and their political awareness yet it does make people curious and ask questions and dig a little deeper. There are many elements in our clothes that express a strong Pan African philosophy calling for African unity and proclaiming African pride. A lot of our themes and stories tie back to that agenda. Even if we can just create awareness of these stories and get people to engage with African history and get a deeper understanding of the rich cultural heritage of our country and continent, I think we have done our part.”

“By incorporating a powerful struggle slogan into our clothes I by no means pretend that we are immediately having a powerful impact on people and their political awareness yet it does make people curious and ask questions and dig a little deeper. There are many elements in our clothes that express a strong Pan African philosophy calling for African unity and proclaiming African pride. A lot of our themes and stories tie back to that agenda. Even if we can just create awareness of these stories and get people to engage with African history and get a deeper understanding of the rich cultural heritage of our country and continent, I think we have done our part.” Julian expressed that communicating this through various media is an important way to reach different kinds of audiences. In addition to their ‘

Julian expressed that communicating this through various media is an important way to reach different kinds of audiences. In addition to their ‘ “We are witnessing a revolution in thought and an emancipation that is allowing people to rid themselves of these social shackles and to celebrate their ethnicity and culture. Such movements of awareness have previously been witnessed in the 60s for instance in the US, where they were spear headed by institutions such as the Black Panther Party. Our current range, the Butan ‘Hidden Panthers’ collection, pays homage to that particular movement and its philosophy.”

“We are witnessing a revolution in thought and an emancipation that is allowing people to rid themselves of these social shackles and to celebrate their ethnicity and culture. Such movements of awareness have previously been witnessed in the 60s for instance in the US, where they were spear headed by institutions such as the Black Panther Party. Our current range, the Butan ‘Hidden Panthers’ collection, pays homage to that particular movement and its philosophy.”