For a while now, MaXhosa Africa has been a beacon of luxury that showcases the beauty and versatility of the African continent. The brand’s mission seeks to reposition culture as a prominent and influential thought leader in society, not just for the present, but for generations to come. Of course, as these values align with BubblegumClub’s own, we have kept our eye firmly focused on the inspiring trajectory of this homegrown brand.

A South African knitwear brand founded by Laduma Ngxokolo in 2012, it all started as a thesis project at Nelson Mandela University. Inspired by his Xhosa heritage and the traditional male initiation ceremony, Amakrwala, Ngxokolo’s signature aesthetic is a contemporary interpretation of traditional Xhosa beadwork patterns, symbols, and colours. His collections are known for their geometric patterns and vibrant hues.

Over the years, the brand has expanded to include not only fashion but also accessories and home decor. It has gained worldwide recognition, with Ngxokolo winning prestigious awards such as the Vogue Italia Scouting for Africa prize in 2014. His designs have been worn by celebrities like Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, and John Kani, and a MaXhosa cable-knit sweater was featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s Is Fashion Modern? (2018) exhibition in New York City.

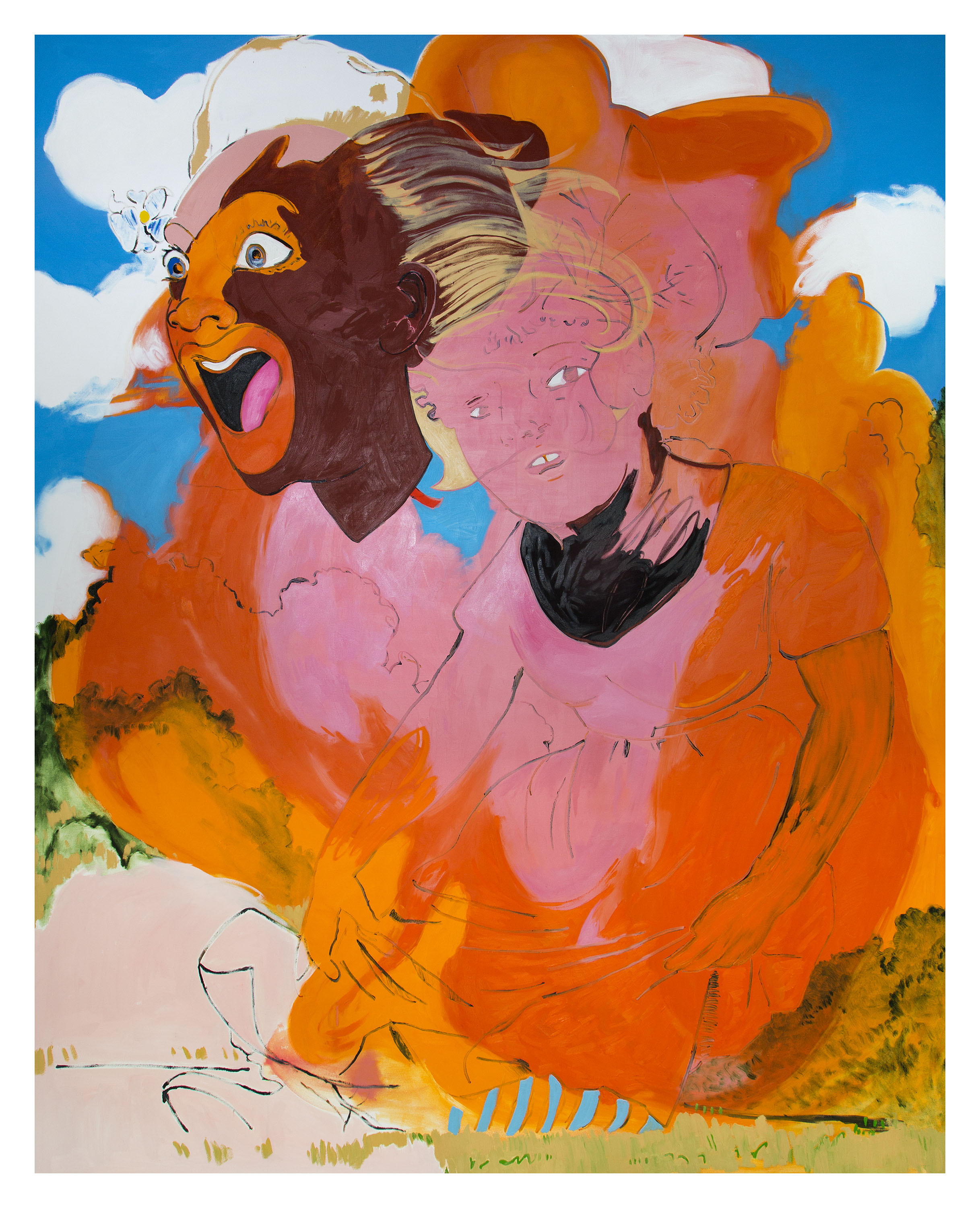

MaXhosa Africa recently launched its SS23/24 collection at Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town. The choice of venue was strategic and marked the start of a significant partnership between the fashion brand and the museum, with MaXhosa’s distinctive homeware incorporated into the Zeitz MOCAA member’s lounge. This show was MaXhosa’s debut solo show in Cape Town. Held so close to their V&A Waterfront store, it was bolstered by the museum’s unwavering support for contemporary African creativity and its unique architectural design.

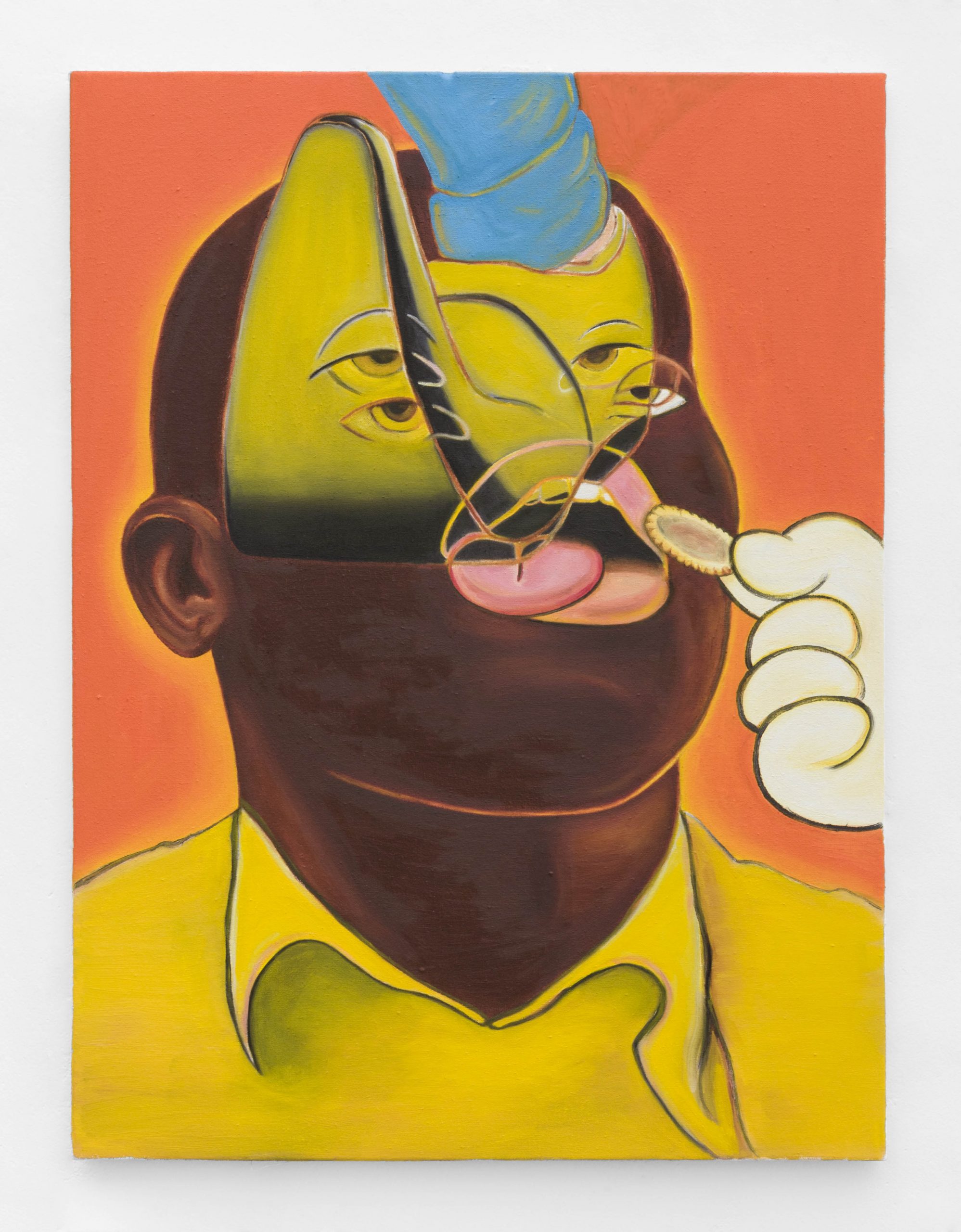

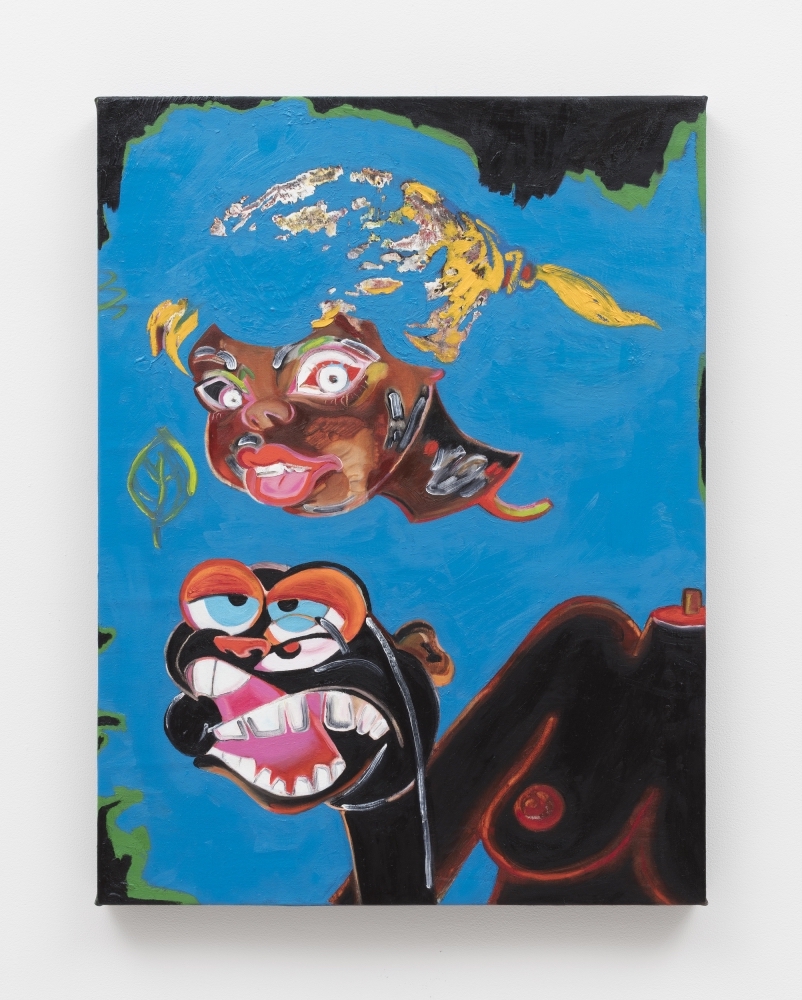

The futuristic extravaganza was nothing short of stunning as models descended the museum’s central glass elevators, which served as a cosmic gateway. Drawing inspiration from African folklore, astrology and spirituality, the collection, aptly named A.S.T.O. (African Space Travellers Organisation), featured an impressive line-up of 80 looks. One of the most notable aspects of the show was the diverse range of models, representing various body types and gender identities found across the African continent.

The show introduced several standout pieces poised to become timeless classics for the brand. Among these were panelled knits and patchwork accents on dresses and suits. The range merged tradition with innovation, introducing new additions such as summer-ready printed t-shirts and swimwear pieces, cutouts and coverups featuring MaXhosa’s signature monogram patterns. By taking the collection to the poolside and oceanside, MaXhosa demonstrated the versatility of its design aesthetic.

At a press conference held ahead of the show, its Founder and Creative Director Ngxokolo said, “MaXhosa Africa is at once a heritage brand and a brand that reflects the Zeitgeist in Africa, bringing the stories of the continent to an international community … We are in the business of pushing boundaries while continuing to honour our African heritage and style. We are part of the group demystifying the aesthetic that African designers cannot compete with the big players in the luxury space.”

The event was a smash hit and saw a snazzy guest list, including media professionals and a whos who of Cape Town’s fashion, design, and art scene. Well conceived and efficiently organised, it was an undeniable testament to MaXhosa Africa’s unstoppable influence and significance within the fashion industry. With such a stellar track record of innovation and excellence, this iconic African fashion house promises a future brimming with even more transformative and neoteric undertakings. We can’t help but be left thirsting for more!