Bubblegum Club released their first cover story on the 26th of January 2016, and since then, have continued to announce new covers every two weeks. Their goal, at the end of January 2017, is to look back at twelve months of images and narratives, contextualise their position as a platform that offers an alternative aesthetic and commercial space. In looking back with an analytical and critical eye, they hope to identify and re-focus their goals, as well as correct their direction when necessary. Recognising who they are, what they do best, and what’s important to them as they reach into the future, Bubblegum Club will better able to better strategise for successful ventures in the coming years.

Bubblegum Club as cultural artefact and platform of living practice

Bubblegum Club is a platform for culture, fashion, music, and art in South Africa offers an alternative to that tired, old visual song. Its images and narratives balance on the nexus between fine art, photography, performance and urban consumer fetishes – everything from global brands like Adidas to niche clothing products– to offer better advertising and marketing possibilities for large corporations and young entrepreneurs alike. Bubblegum Club forms a bridge between “scenes” created between formal, institutional spaces who guard access and privilege, and innovative, interdisciplinary artists and cultural producers – those who cannot, and do not wish to frame their cultural production in accepted ways — who have less access to such formal space.

That refreshing attitude – giving shout-outs to both “high” and “low” culture, art and commerce is apparent in the interviews featuring art-entrepreneurs like Russell Abrahams, founder and Creative Director of the illustration studio Yay Abe (Yay Abe – new vision for illustrative work and edgy performance artists like Dineo Seshee Bopape (Artist Dineo Seshee Bopape on Soil, Self and Sovereignty. The platform capitalises on the use of the body as design, and “design for the body” through recognising the ways in which urban youth fashion their physical bodies and clothing into “high” art. Here, the body replaces the white cube gallery and the history museum; material objects that are part of self-fashioning – including clothing, shoes, and jewellery, music, movement, choreography and styling – become part of what goes on the dynamic walls of skin and psyche.

In effect, Bubblegum Club is a cultural intelligence agency – it is a cultural artefact of its own, and a platform for a living practice. It avoids clichés – the fluff and easily digestible consumer culture – celebrated without critique and self-awareness. Their focus is quality and innovative design over throwaway materials. It helps young creative (designers, musicians, artists, choreographers, stylists, thinkers) infiltrate formidable formal structures. In the absence of open avenues, they aim to create their own continent – a space to create, be, grow, share. It is a space in which cultural production is highlighted, but also critiqued – a place in which we can be insightful, and not be force-fed a trend that will leave us empty and regretful about our consumption after an hour.

Challenging perceptions that limit self-making

On this platform or stage, Bubblegum Club provides “actors” (or cultural producers) and audiences with the tools and avenues to explore in that journey; they offer innovative possibilities for changing and challenging social perceptions that limit our conceptions of self. They can also engage with local history and get a political education, whilst being entertained by dope visuals and easy-to-read articles and interviews. During the past twelve months, their cover pages on the “Features” section have been visually striking, provocative, and innovative. “Features” foregrounds urbanity and highlights the myriad avenues available to cosmopolitan youth through provocative self-fashioning. We see this in fashion articles like the feature covering the aesthetic of I.AM.ISIGO, a clothing design company that based between Nigeria, Ghana and France (I.AM.ISIGO – Transcontinental Thread). I.AM.ISIGO offers possibilities beyond the limited options of mega brands from the US that whitewash personal style; it also offer us the possibility of dreaming of the larger possibilities offered by other African design centres like Ghana.

On the other end of the spectrum, we also get to question conventions. Lady Like – The fabrication of femininity, brings “attention to the various ways femininity is assigned particular attributes through the use of fabric, stitching, styling, photography and painting”; rather than offering us models in lacy underwear, we get to interrogate the ways in which we accept the constraints placed on women. In their interview with iconic artist Mary Sibande, we get to “blow up” the constraints that have been placed on the “black imagination” – and free ourselves, like her iconic sculpture of a domestic worker, Sophie, through daily acts of rebellion and dreaming.

Context: problematic perceptions visual imaginary on Africa

“Africa” remains a monolithic space of violence and poverty uncomplicated by global politics and military action because the images and narratives chosen by powerful news agencies and newspapers continue to speak to foundational myths that Europe (and white ex-colonists and plantation owners in America) manufactured about Africa. Even now, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, images of Africa in news, fashion, popular narratives – especially those produced for consumption in the geopolitical West – continue a conversation with centuries-old work that constructed the African as somehow less human, less civilised, and (somewhat sexily) savage. Myths about “Africa” remain so powerful that contemporary visitors, fashion shoots and news journalists alike attempt to recreate the fantasy – ignoring, often, the complexity of modern realities – in order to reference those influential narratives that still have a claim to “truth” in our collective imaginary. Audiences and photographers themselves are often unaware of how these images and advertisements continue a troubling colonial legacy.

The frequent-culprit list: everything from European destination wedding photography, aid workers’ and travel writers’ blogs, and even fine art photography from Africa by African-born artists. Often, their “Africa” shoot is accompanied by images of animals, vast vistas, and “colourful natives” – manufactured the foundational mythologies about African landscapes and African people that remain with us in the twenty-first century. One only needs to Google the words “Africa” and “fashion” to get an idea of what’s out there:

Even though many of these striking photographs were taken in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the persona of the African is “stilled” – immobilised in time as something primordial, fashioned as something belonging to the past. They are still wearing clichéd “tribal garb”, practicing customs that are sometimes constructed as quaint, and at others, as harmful to women and children. On a fundamental level, they are present in the photographs to highlight the powerful personas of the white, superior European subjects – who have the luxury and ability to self-fashion themselves in modernity.

Offering an alternative visual narrative

Despite that overwhelming body of problematic images, hope is not lost. The technologies of photography are also a useful tool that helps us change and challenge tired, old views. We can train ourselves to identify the ways photography often repeats and reinforces colonial views of Africa and Africans. From there, we can consciously create an alternative image repertoire for this, and subsequent generations. Bubblegum Club gets that the present generation reads the world almost exclusively through images. In this age where images play a significant role in how we read the world, photographs that accompany branding narratives have even more influence. But we often read only as uncritical consumers; we read without critiquing the images, or the personal (and national) history that we bring into our reading of images. We rarely think about how our image “bank accounts”, and our processes are influenced by history and culture – history that aided violent, imperial ventures that depended on portraying “Africa” and “African” as somehow less than, Other, savage.

That process of educating its public to be critical, analytical readers is an essential part of Bubblegum Club’s fabric. Branding and selling, together with playful re-educating and conscientising is the most significant aspect of the project, evident in Features such as Everything you need to know about Fak’ugesi African Digital Innovation Festival 2016, Eating as activism: Parusha Naidoo’s intersectional approach to our plates; Dillion S. Phiri – Social sculptor shaping African youth.

That awareness means that within Bubblegum Club’s pages, there are often ironic winks at anthropology (that overarchingly influential field that helped constrain “African-ness” and “blackness” in particular within strict borders that aided colonial conquest and racialisation), sexual politics, “traditional” tropes of femininity and masculinity. Instead, we are offered dynamic possibility, and subtly made aware of the influence of archival footage on the present. Their Features focus on identity formation with an acute awareness of the impact of history on the present, for clothing that plays with the multiplicity that is South Africa’s “heritage”, music that harkens back and looks forward, for collaborations that do not – above all, trap one within short-sighted borders of nation, race, gender, sexuality, and other markers of lazy identity politics.

Their “interventions” are evident in features like Tackling the Tracksuit: Youth95’s New Capsule Collection; Multiplicity on the Dancefloor: nightclubs for the non-binary; Durban’s viral dance videos highlight the prescience of social media and the mobile phone in youth culture.

Bubblegum Club’s strength is in that they operate in the in-between place of fine art and marketing, positioning themselves as provocateurs and providers of critical educations and our desire to fashion ourselves – to assemble and re-assemble our personas in order to signal desirability and power, to position ourselves as central within the flows of global modernity, and to affect and impact those flows, rather than simply react to what’s popular in America or Europe – using material and symbolic objects that speak to our own psychological needs.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York-Oswego, and an Honorary Research Associate at the Centre for Indian Studies in Africa (CISA), University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa). She was a senior editor and contributor to the online magazine, Africa is a Country, from 2010-2106. Her writing is featured in Transitions, Contemporary &,Al Jazeera English, Art South Africa, Contemporary Practices: Visual Art from the Middle East, and Research in African Literatures. She writes about and collaborates with visual artists.

“By incorporating a powerful struggle slogan into our clothes I by no means pretend that we are immediately having a powerful impact on people and their political awareness yet it does make people curious and ask questions and dig a little deeper. There are many elements in our clothes that express a strong Pan African philosophy calling for African unity and proclaiming African pride. A lot of our themes and stories tie back to that agenda. Even if we can just create awareness of these stories and get people to engage with African history and get a deeper understanding of the rich cultural heritage of our country and continent, I think we have done our part.”

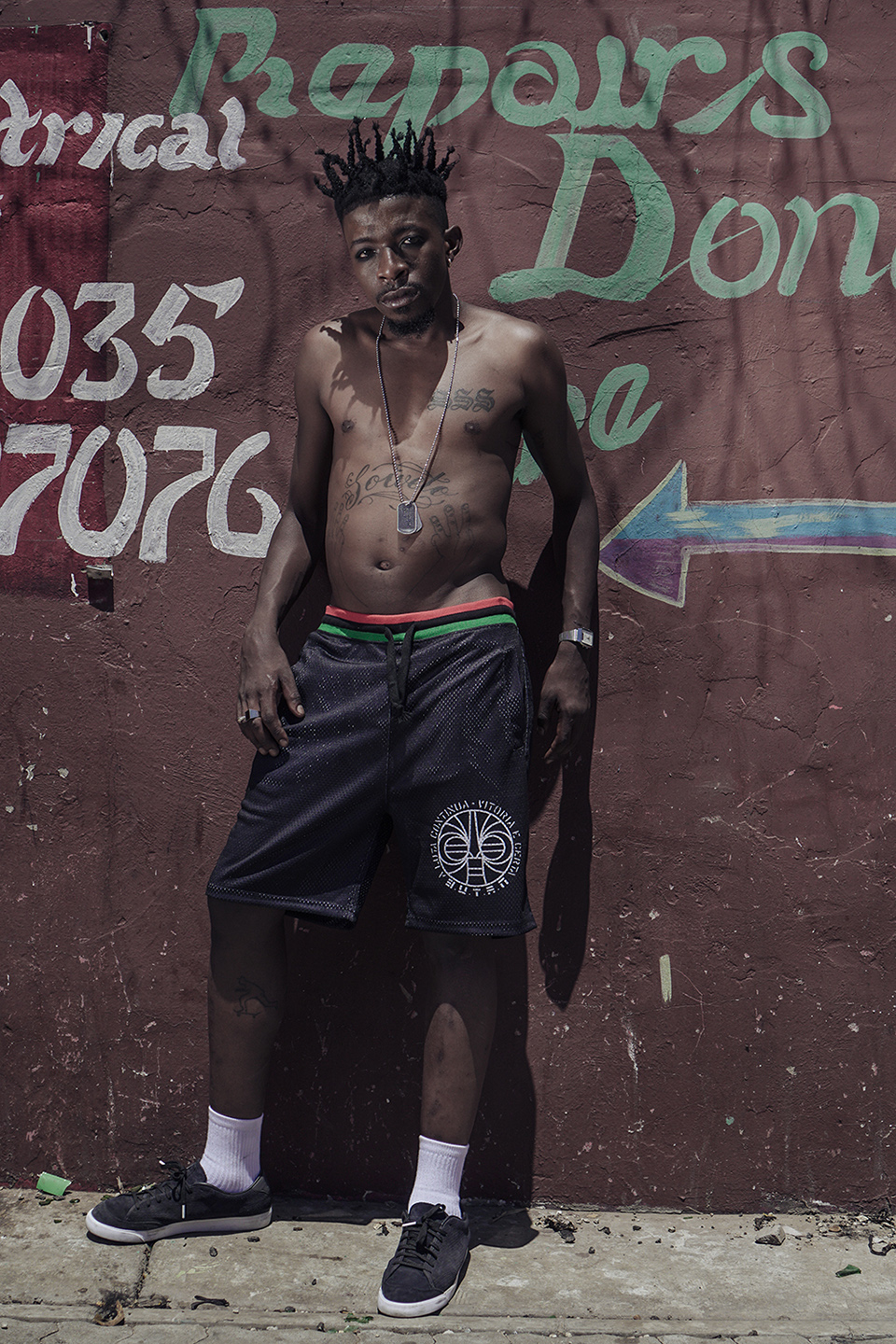

“By incorporating a powerful struggle slogan into our clothes I by no means pretend that we are immediately having a powerful impact on people and their political awareness yet it does make people curious and ask questions and dig a little deeper. There are many elements in our clothes that express a strong Pan African philosophy calling for African unity and proclaiming African pride. A lot of our themes and stories tie back to that agenda. Even if we can just create awareness of these stories and get people to engage with African history and get a deeper understanding of the rich cultural heritage of our country and continent, I think we have done our part.” Julian expressed that communicating this through various media is an important way to reach different kinds of audiences. In addition to their ‘Aluta Continua‘ lookbook created in collaboration with Bubblegum Club, Butan decided on a short film. This incorporates the significance of ‘Aluta Continua’ with conversations between hair stylist Mimi Duma and makeup artist Shirley Molatlhegi. In between shots displaying the collection in the streets of Kliptown, Mimi and Shirley share how they encourage people of colour to be proud of their skin and their hair. This connects to the foundational concepts for the collection, and the Butan philosophy.

Julian expressed that communicating this through various media is an important way to reach different kinds of audiences. In addition to their ‘Aluta Continua‘ lookbook created in collaboration with Bubblegum Club, Butan decided on a short film. This incorporates the significance of ‘Aluta Continua’ with conversations between hair stylist Mimi Duma and makeup artist Shirley Molatlhegi. In between shots displaying the collection in the streets of Kliptown, Mimi and Shirley share how they encourage people of colour to be proud of their skin and their hair. This connects to the foundational concepts for the collection, and the Butan philosophy. “We are witnessing a revolution in thought and an emancipation that is allowing people to rid themselves of these social shackles and to celebrate their ethnicity and culture. Such movements of awareness have previously been witnessed in the 60s for instance in the US, where they were spear headed by institutions such as the Black Panther Party. Our current range, the Butan ‘Hidden Panthers’ collection, pays homage to that particular movement and its philosophy.”

“We are witnessing a revolution in thought and an emancipation that is allowing people to rid themselves of these social shackles and to celebrate their ethnicity and culture. Such movements of awareness have previously been witnessed in the 60s for instance in the US, where they were spear headed by institutions such as the Black Panther Party. Our current range, the Butan ‘Hidden Panthers’ collection, pays homage to that particular movement and its philosophy.”