Our discussion would be held at one of Joburg’s popular high-end speciality stores, chosen for its open Terrace restaurants that would allow for the best enjoyment of the warm morning rays.

Milisuthando Bongela arrived in her Sunday best. Wrapped in a confidence and strength that hinted at the unwitting voyeur, that this woman had set her own path. Having studied Journalism at Rhodes University, established the successful blog Miss Milli B and having recently been appointed as the editor of the arts section of the Mail & Guardian, she has already accomplished so much. I wanted to find out about the ideas and the driving force behind this black woman’s power. I wanted to know how she defines her place in our “New South Africa.”

It’s at this country’s contradiction where our conversation takes flight. Where spaces of subduing luxury are a short distance from an energy filled city centre, with stores filled to the brim with cheap Asian goods and low priced vegetables sold on bustling side walks. Milisuthando speaks of how this luxury, such as the restaurant that we found ourselves in, would cater to a demand for leisure, a leisure that is at the very heart of “white life”.

Milisuthando is not afraid to deal directly with what she considers the crux of our country’s racial challenges in that white privilege continues to exist even though we have a constitution that provides for the equal rights for all her citizens.

Leisure as the site of our problems

She makes mention of how our current day acts of leisure is how the spoils from the conquered are enjoyed. Even now we find colonialism still being justified in such performances of indulging in a colonial past. She gives the example of her recent visit to a restaurant that featured cocktails named after dead English writers, with walls covered in Moroccan themed tiles and cast iron sculptures of a cow riding figure. Such nostalgia seeks to remind us of a time where racial hierarchies are actively enforced. It seeks to symbolically recreate moments of power without making a challenge to the prevailing inequalities.

It is in this space of leisure that Africa continues to find herself. I make reference to the example of how our continent has become a hot bed for volunteerism where one’s tourist experience is focused on volunteer work. It is through such “charity” that those from the global north come to gain their humanity by engaging with those deemed destitute and in need of saving.

Milisuthando identifies the global south as historically being the place where such privileged bodies are able to perpetuate themselves through “naturalist study”. The beginnings’ of anthropological discipline was one where black communities were seen as living in a past and natural state. The knowledge from here would be used to justify a false contrast to western bodies. Those whose studies would never turn this gaze on themselves and question how their ideas would be used to perpetuate a prevailing inequality. Milisuthando takes her analysis forward discussing how to this day “we never have the space within our own work to ask ourselves these very same questions.”

Within her own work she finds herself asking the same hard questions. She loves to work with beautiful things but then asks to what end are these pleasures for?

Describing herself Milisuthando writes:

“I believe we are in an era where substance and what comes out of your mind rather than what you are wearing will be more important for the survival of our sanity as a human race. So while fashion and beauty are necessities in urban life, I’m not particularly interested in the seasonal trends of either, but rather fashion and beauty, as well as art, film and literature as mirrors of where we are as a culture.”

For her the ethics of what we do cannot be ignored.

It is in this same blog that the black woman features prominently in her online work. One sees images of beautiful black woman as creators of cultural content. She features Black models making waves on British catwalks, to a post on a modern day Sangoma who tackles the issue of money and love and even a beautifully shot film dealing with sisterhood and friendship. For Milisuthando it becomes important to deal with the issues affecting black life in her work. She has especially taken on this task on her newly acquired platform at the Mail & Guardian.

For her our work must be one steeped in the ethic. The goal can no loner be one of equality. “What use is equality when we cannot use it to make a positive difference?” Milisuthando calls for the empowerment of a people so that they can liberate themselves, changing the very structures that ensure their repression.

Our current problems have been very much made by those with power. It is wealthy corporations that destroy the livelihoods of others through their ecologically destructive industries that allow for our economic “development”. Even our current lifestyle trends are steeped in such discourse as it is only the rich who are able to afford the organic non-GMO foods and yet it is through their wealth that such a need for more “safe food” is created. Right now unhealthy processed food is being sold to poor communities at discounted prices, I interjected. She agrees stating how when one needs to eat one must eat, “they have messed up the earth and now only the rich can be healthy.”

Yet this idea of rich and poor is not the full picture. Milisuthando argues that we still follow the very same system of making money and doing business that the so-called rich are also using. She calls on a need to look outside of the capitalist system that has already disconnected us so much from the environment that now finds itself “discovered” in such leisurely fads as being organic or healthy.

Milisuthando makes reference to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie by describing our situation as being of one where “we have come full circle.” We seem to be in this pattern of returning to a “healthier” past. It’s this system that reduces who we are so that we find ourselves constantly needing to “re-discover.” She argues against this “going back” as she was never really separated from an environment and nature in the first place. “I am already here and don’t need to return. I must just be conscious?” Having had to exist in Jo’burg means having to buy into the ides of acting individualistically, of being disconnected and needing to reconnect through materialist consumption.

Working at the Mail & Guardian

The Mail & Guardian is still very much a business and Milisuthando in taking up the position there would have to adjust to a commercial medium with its even much larger readership base. Now she would be speaking to an even more diverse crowd but would also need to be able to write about their stories. Milisuthando was more than ready for the task as the newspaper hired her because of the earlier work she produced for her blog. Those very ideas brought her here but now she would have to adapt their message to a different platform.

So she did her research and went online looking at the content that got the best responses. She found that her most successful pieces were the ones that didn’t rely on jargon. Milisuthando would begin to engage in sort of “self censorship” but not one in which she didn’t want to offend. Her goal would be to find ways in which she could better connect with her readers. She would begin “appealing less to the head and more to the heart.” The focus of her work would be about moving away from the “intellectual talk” that she considers to be very much exclusionary to those who do not have the full command of the English and academic language. “Jargon does not disrupt the space and also serves to perpetuate the oppressive language of the dominant”. Within a white supremacist world we are constantly excluded from knowledge through language and so Milisuthando would look to appealing to our hearts in order to include more people in the discussion.

Where black people have had their fire extinguished she has had to find new ways to include them but in ways that are not anti-white. Her work is already having an impact and readers are now sending letters, a new thing for the arts section of the newspaper. Her readers are starting to take the arts seriously, no longer relegated the site of leisure but one whose enjoyment was also “consciousness”. It is through a narrative that one begets feelings and where people can start to engage and interrogate ideas. This is her goal as writer for Mail & Guardian to use the narrative to start the much-needed discussions.

Towards a Consciousness as solution

Here is where her work draws its power. It is through her own experiences that she is able to connect to her readers. Her political end goal becomes one in which you have to shed a self that is based on material possession and holds an individualistic understanding on relationships. One must critically evaluate themselves, finding and identifying new goals that will allow us to function as a black collective in achieving our new found desires. Milisuthando makes reference to an Ubuntu whose sense of shared values is one crucial to understanding a liberation that cannot be achieved alone.

She further identifies anger as also being vital to the cause in its ability to rouse our political consciousness. It is not enough to burn the paintings. “Yes I can be angry but I, as a writer, am also more.” She is more than just her black anger but also a black body striving for something beyond a place of pain.

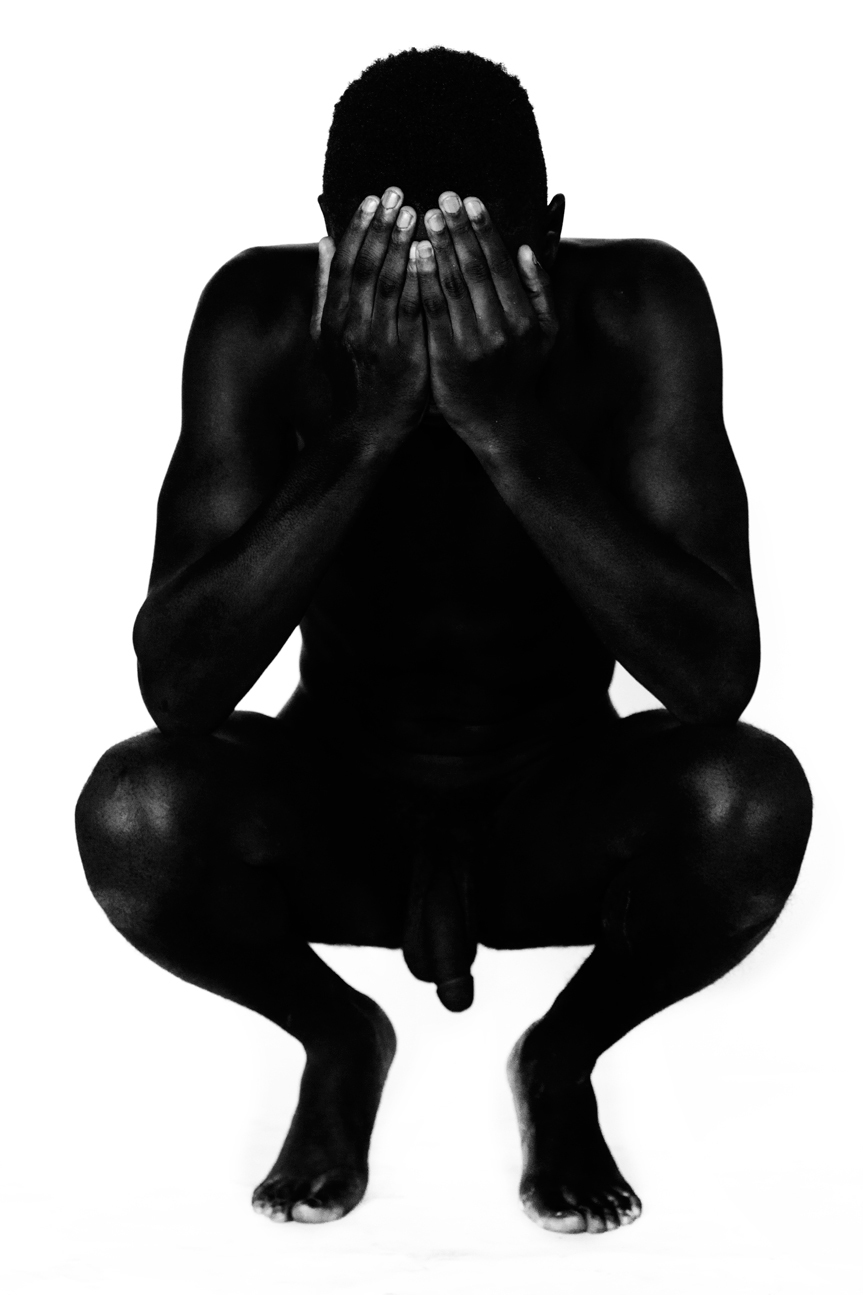

Living in a white supremacist world means “being stripped down to our physical form, robed of our ability to fly.” A black consciousness becomes one where we are forced to engage with such processes beyond our direct control. For her, spiritual mediums are the ones who understand such connection and such a consciousness becomes a form of metaphysical awakening on an intellectual level. Yet such metaphysical and intellectual, should not be seen as distinct as one cannot function without the other.

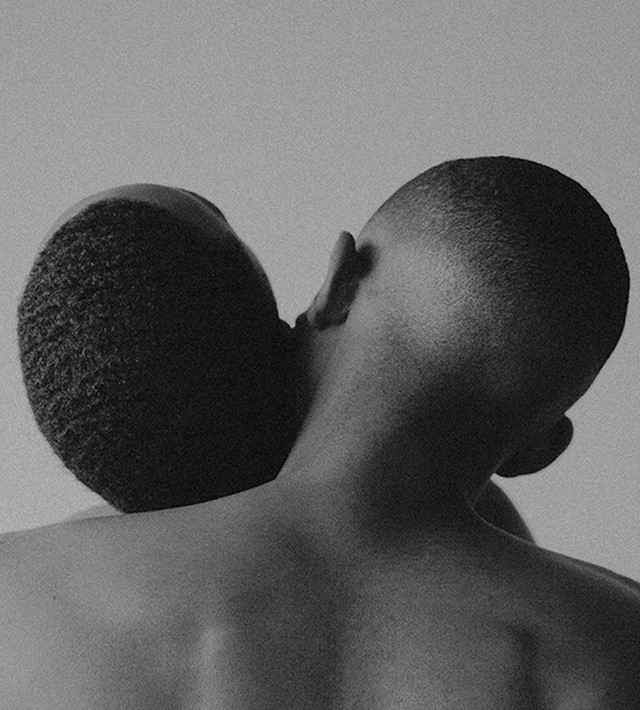

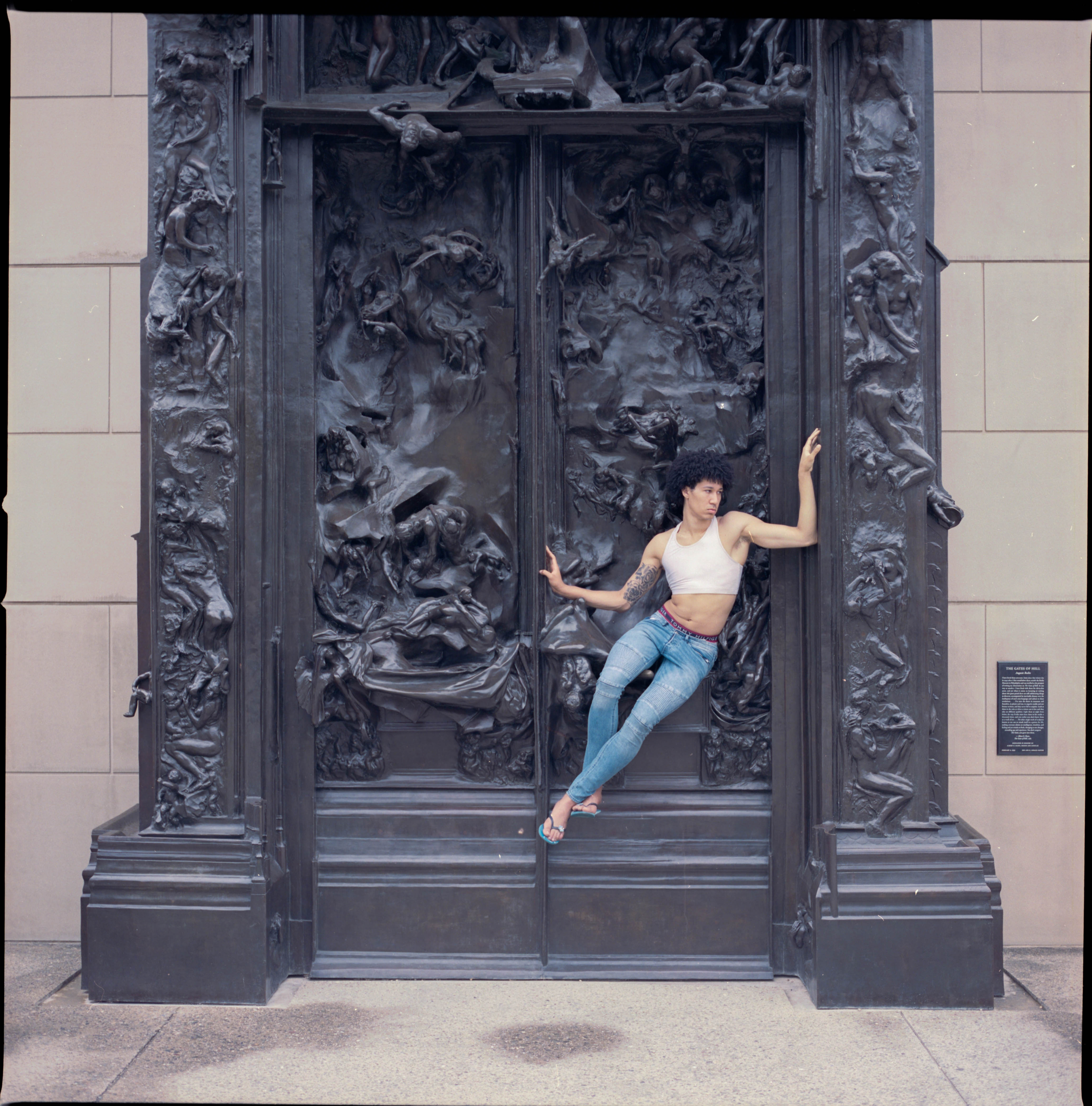

It is here that our discussion, in a sense, came to its full circle. It is here Milisuthando’s love of beautiful things would make a deep connection with me. It is amongst the beauty that she can escape the pain and enjoy life. Yet for her experiencing such cannot be without responsibility and has, like this current generation of black creators, taken on the torch to create a beauty that does not come at the expense of another’s power. It is in this creation of a space where not only black is the beautiful but is also a safe space in which a black beauty can also thrive.

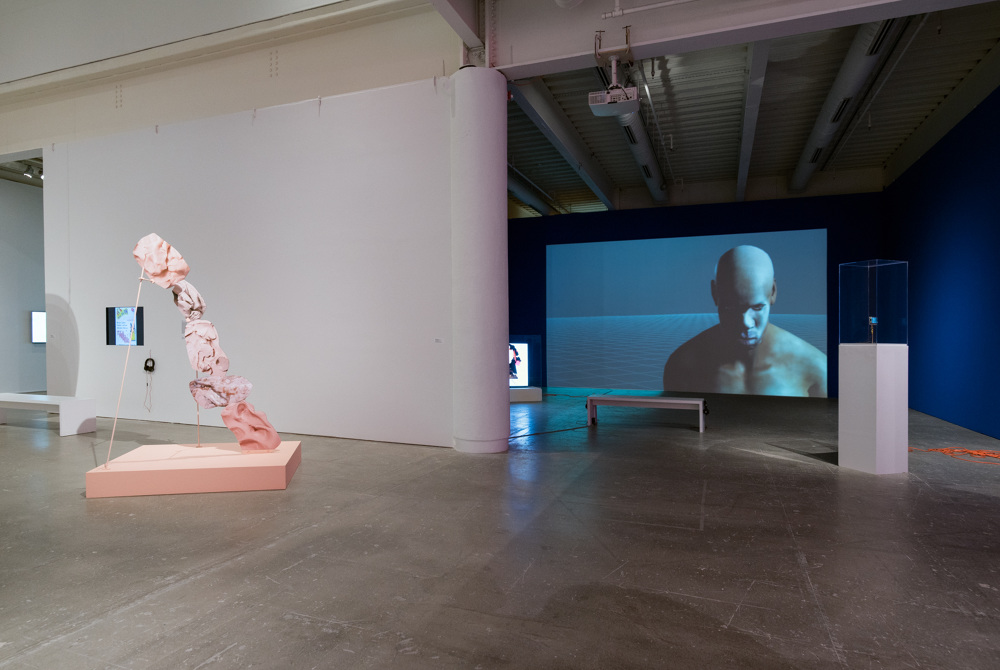

[all photographs taken in the Johannesburg Art Gallery]

The two tapestries featured are The Zulu Kraal, by various Rorke’s Drift Weavers(1973) and The Israelites Crossing the Red Sea by Jesse Dlamini, Miriam Ndebele & Josephina Memela (all of Rorke’s Drift)

From the Pre-Raphelite room, the painting featured is “St. Elizabeth of Hungary” by James Collinson