London-based, multidisciplinary art collective sorryyoufeeluncomfortable in collaboration with The Gallow Gate present the exhibition and programme (BUT) WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY? as part of the Glasgow International 2018 Supported Programme. For the exhibition collective members Christopher Kirubi, Halima Haruna, Rabz Lansiquot, Mayfly Mutyambizi, Imani Robinson and Jacob V Joyce respond to the programme title. The exhibition will be surrounded by talks, workshops, performances and a film screening, with the intention of inviting audiences to engage with questions related to racial tensions, representation, translation and the experiences of people of colour. I interviewed Imani and Rabz to find out more about sorryyoufeeluncomfortable and the programme they have curated.

Please share more about the Baldwin’s Nigger Reloaded project and how it led to the formation of sorryyoufeeluncomfortable.

The Baldwin’s Nigger Reloaded project was started by Barby Asante [London-based artist, curator and educator] and Teresa Cisneros [cultural producer who has worked as arts manager, curator and arts educator] in 2014. They did a call out for young artists and thinkers to respond to Horace Ové’s 1968 film Baldwin’s Nigger; a documentary in which James Baldwin gives a speech and answers a series of questions from a London audience. Over 10 weeks we came together to respond to Horace Ove’s 1968 film Baldwin’s Nigger, focusing on the contemporary relevance of the themes that emerge in the film, and James Baldwin’s thought more generally. We produced artworks, performances and workshops which were showcased in a one-day event at Rivington Place [visual arts centre in London]. It was this project that brought the collective together and kick started our journey. Baldwin’s Nigger Reloaded was developed into a performance created by Barby Asante which has been shown at Nottingham Contemporary, Art Rotterdam, Tate Liverpool & The James Baldwin Conference, Paris, and will also be shown as part of Glasgow International Festival in May.

Please share more about the name for the collective, and the thinking behind making this the collective name?

During our residency at Iniva [Institute of International Visual Arts in London] in 2014, we knew we wanted to take the collective beyond the BNReloaded project and our initial reasons for coming together as a group. sorryyoufeeluncomfortable was a brilliant fit for us. It articulated what we couldn’t always vocalise in art spaces, which are so often spaces of privilege, exploitation and palatable politics. As a majority non-white, non-heterosexual group of artists and thinkers we were often made to feel unwelcome in art spaces, with both our politics and our being-in-the-space always seeming to make other people flinch. sorryyoufeeluncomfortable is a flipping of the script. The name operates with multiplicity, it’s shady and sarcastic and on-the-nose and also an act of care and recognition for each other.

How has the collective evolved over the years?

The collective began with the BNReloaded project, with 16 members who were between 18 and 25 and artist Barby Asante & curator Teresa Cisneros as our mentors and primary producers. The collective actually works more like a network or community of artists now, who are working around similar themes and having concurrent conversations, so members appear and disappear on a project by project basis. At the moment the collective is being led by 4 people, with Rabz Lansiquot and Imani Robinson producing, programming and curating the work and Jacob V Joyce and Zviki Mutyambizi in supportive roles. We also have a fluid group of contributors and mentors, including Barby and Teresa who have remained close collaborators. The work shifts according to people’s primary interests but the central thread is always radical & liberatory politics and what it means to be living and working in the current climate.

Where did the title for the programme come from?

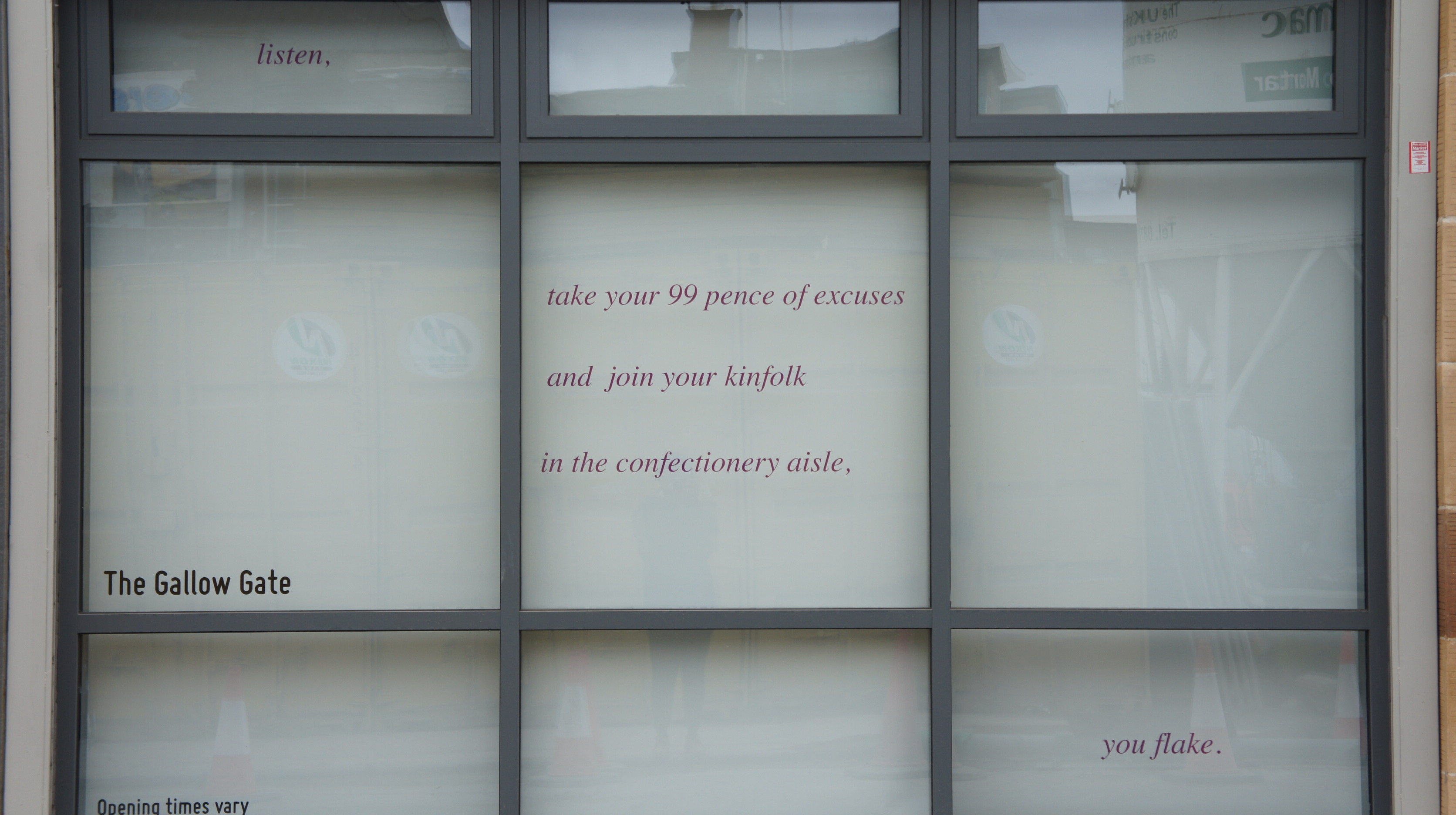

If you’ve ever asked a white person (be they a friend or a stranger) what they are doing about white supremacy, you’ll probably have an anecdote about a slow descent into an array of exaggerated emotions ranging from anger, to tears, to shouting and storming out. If you’ve never asked this question, brace yourself. The title (BUT) WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY? acts both as a refusal (you come here expecting me to tell you what to do, but I only show you my art and make you see what you already know) and an acknowledgement that we are forced to share our lives with white supremacy. The question is all of ours… The question looms and it persists… the question is tiresome… the question is discomforting. The 6 Black artists in the show respond in loose or direct ways to the title question, for example, they may invert the question in order to ask: “What is white supremacy doing to you?”, or they may suggest that as Black artists, to make work of any subject matter, or of none at all, is to resist, to survive and to “do something”.

Share with our readers the visual choices for the title (including the word ‘but’ in brackets and writing the title in capital letters)

We knew that the audience for GI, and many art festivals, is mainly white and largely made up of arts professionals. As Black artists we wanted to speak to the consumption of the work of artists of colour, which is often at our own expense. The title is as much an address to our audience as it is a provocation for the artists – who cannot help but be faced with the question. Audiences are engaging with our work, which is variably about Black pain and Black death, but what are they doing to address their complicity in that, or to amplify the voices of those already fighting for liberation? What are the art-world audiences doing about sustainable living and working conditions for Black artists? And how are they engaged in material transformation within the institution?

The capital letters signify the affect and the urgency embedded in the articulation of this question, the heaviness of the question and the way it feels somewhat impenetrable to exist or escape as a Black person in this world. Sometimes a shout reaches further than a whisper…. or sometimes a shout is the only way you will be heard. And the brackets are there as a preconceived comeback to a series of tired, self-preserving responses that do not answer the question.

Why do you think it is important to combine making and writing for the interrogation of the title?

The artists in this show Halima Haruna, Jacob V Joyce, Christopher Kirubi, Rabz Lansiquot, Mayfly Mutyambizi and Imani Robinson all have varying practices. sorryyoufeeluncomfortable is a multi-discplinary collective; a community who make things and who write poetry, songs and prose to activate their practice. (BUT) WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY? is a personal and a political question and we wanted to be able to respond however we liked, or however we could. Sometimes our responses can be vocalised, or put into words, and other times different modes of expression are better able to articulate an answer.

Why do you think it is important for the exhibition to be surrounded by conversations, workshops and performances?

A core part of sorryyoufeeluncomfortable’s work is public programming – creating intentional spaces for radical study and dialogue; it’s very much ingrained in what we do. We wanted the chance to engage with the range of topics and ideas that are present in the work, and to be in dialogue with our audiences who we believe offer as much to us as we can to them.

It’s important to have multiple entry points to the work; to make the work and the ideas surrounding it as accessible as possible for those who it concerns directly, which is all of us in our distinct ways. We also exist within a wide community of artists, filmmakers and writers who have a lot to say; our programming provides a non-hierarchical space within which to engage with multiple perspectives and draw connections.

Please share more about your thinking when putting the structure of the programme together?

We wanted to give our GI audience a taster of each of the kinds of activations we programme. We facilitate workshops & seminars, radical study reading groups, and we also curate film screenings and exhibitions. When we are programming we always aim to create a space for popular education, that is, a democratic space for knowledge sharing in all directions, rather than a one-way street to educate our audiences. In that sense, the structure of the programming also invites audiences to engage in conversation and to participate in the work, rather than solely to consume it.

Please share more about Black British Shorts and why you felt you wanted to have the screening be a part of the programme?

Whilst we were ICA Young Associates in 2017, we curated a programme of shorts films by and concerning the lives and experiences of Black British people. It was a really wonderful event for us personally, as the submissions we received reflected what we already knew from experience, but also showed us new and varying perspectives. The films were of such a fantastic standard; we were really proud to be able to share them. The audience at GI is pretty international so we just wanted to share some of the films again and showcase our extended community of talented Black brits.

Who do you imagine as your audience? And how do you think they will react to or process the exhibition and the programme you have put together?

We definitely hope that our work appeals to Black & POC folk, particularly queer folk, who are also interested in art and radical politics. Those are the people that we make the work for and put events on for and that tends to be the majority of our audience for our work based in London because there’s a pretty strong Queer POC creative community there. We hope that the kind of work we do resonates with the POC community in Glasgow too.

However, we are totally aware of the demographics of UK arts & culture audiences. They are overwhelmingly white and middle-class for a number of reasons and this means that a significant amount of events and exhibitions which deal directly with race politics have a markedly white audience-base. It’s always difficult to balance the desire to create work and share that work with audiences, and the oftentimes disheartening feeling you get when that audience doesn’t reflect your community. This also mixes with uncertainty around what exactly those audiences are taking away, is it simply that they attended this ‘cool’ thing about Black art, or do they actually leave with a changed perspective and a plan for active allyship? – Many people will come to the exhibition expecting it to give them answers to the title question. That’s not the purpose of this show, and that’s part of the gag.

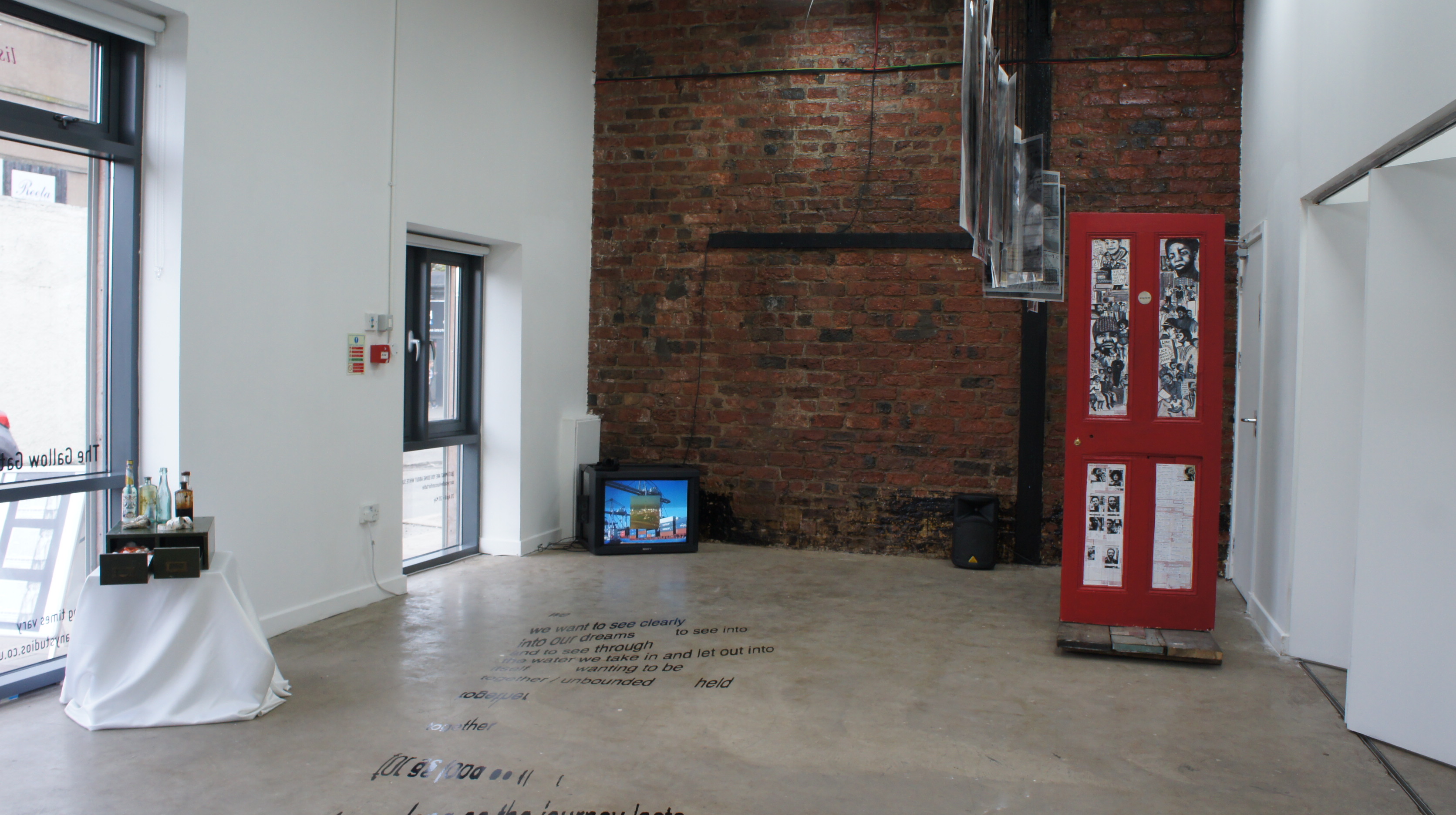

How will the exhibition be constructed and how have you planned to have the various artworks speak to each other?

The process of constructing the exhibition had several parts to it. It began with commissioning the artists: we put together a concept that was broad enough for multiple interpretations but that had a single thread that would tie everything together. As curators we wanted to work with artists whose work and practice we knew well, as this gives us the kind of trust you need to build an artist led curatorial model where all involved are committed to the process of working collectively. Knowing our artists well, and being in conversation with them already, meant we could leave them to their devices and allow the show to come together organically. The magic really happened during the install. When we entered the space we didn’t know what it was going to look like when we finished, and that allowed us the freedom to make it look however we wanted. It was a collective process of trial and error, and of trusting the process and each other implicitly.

As a collective what are some of the texts you use as a foundation for how you think about Blackness, the Black existence, white supremacy, representation and translation? Why do these texts appeal to you?

Because of our origins as a collective James Baldwin is one of our central inspirations because of his employment of loving rage in all of his writings. – There are a lot of readers in our collective and we often read texts together as a collective and as part of public programming. We’ve held events around the work of Sylvia Wynter, Frank B Wilderson III, Fred Moten, Stuart Hall, Audre Lorde, Christina Sharpe, Katherine McKittrick, Black Quantum Futurism, Octavia Butler and CLR James. Our collective conversations around Blackness are always evolving, the more we read and speak to each other, depending on who we are collaborating with, and with each project we work on, wherever we are in the world.

Is there anything else about the collective, the exhibition or the programme that you would like to mention?

We don’t get paid enough to do the work we do and nor does any individual or arts collective of colour we know. It’s a real problem in the art world, never mind the rest of the ‘worlds’. Ultimately, we work because we have to and because we love what we do – but this shit is unsustainable.

(BUT) WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY will be on from 19 April – 20 May.