Buildings mark the moments in our history where a people thrived. Ângela Ferreira’s “South Facing” is the exhibition that marks an important moment in the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s (JAG) evolution. For the artist “buildings can be read as political texts” and this location has its own fair share of history.

She examines the relationship between people and their use of building and public space. The “JAG building is a perfect example for me to reference …It’s controversial history tells the story of the role of art in South Africa and reflects on the incredibly dynamic past and present history of the Johannesburg city-center .”

1912 saw the completion of the Museum building with its North facing extension, completed in the 1980s.This new addition was intended to be a place of leisure, a home within the occupied territories. The exhibition’s curator Amy Watson discusses how “the original building built by a British architect, Edwin Lutyens, [who] built a grand entrance that is South facing, being from the Northern hemisphere he applied this logic. A fence was erected between the park and the Gallery some time ago, with the intention of protecting the collection and ensuring the safety of the gallery visitors and staff.” With the end of apartheid the park would become a leisurely space for all.

Ângela Ferreira, Sites and Services, (1991-1992), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Sites and Services, (1991-1992), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

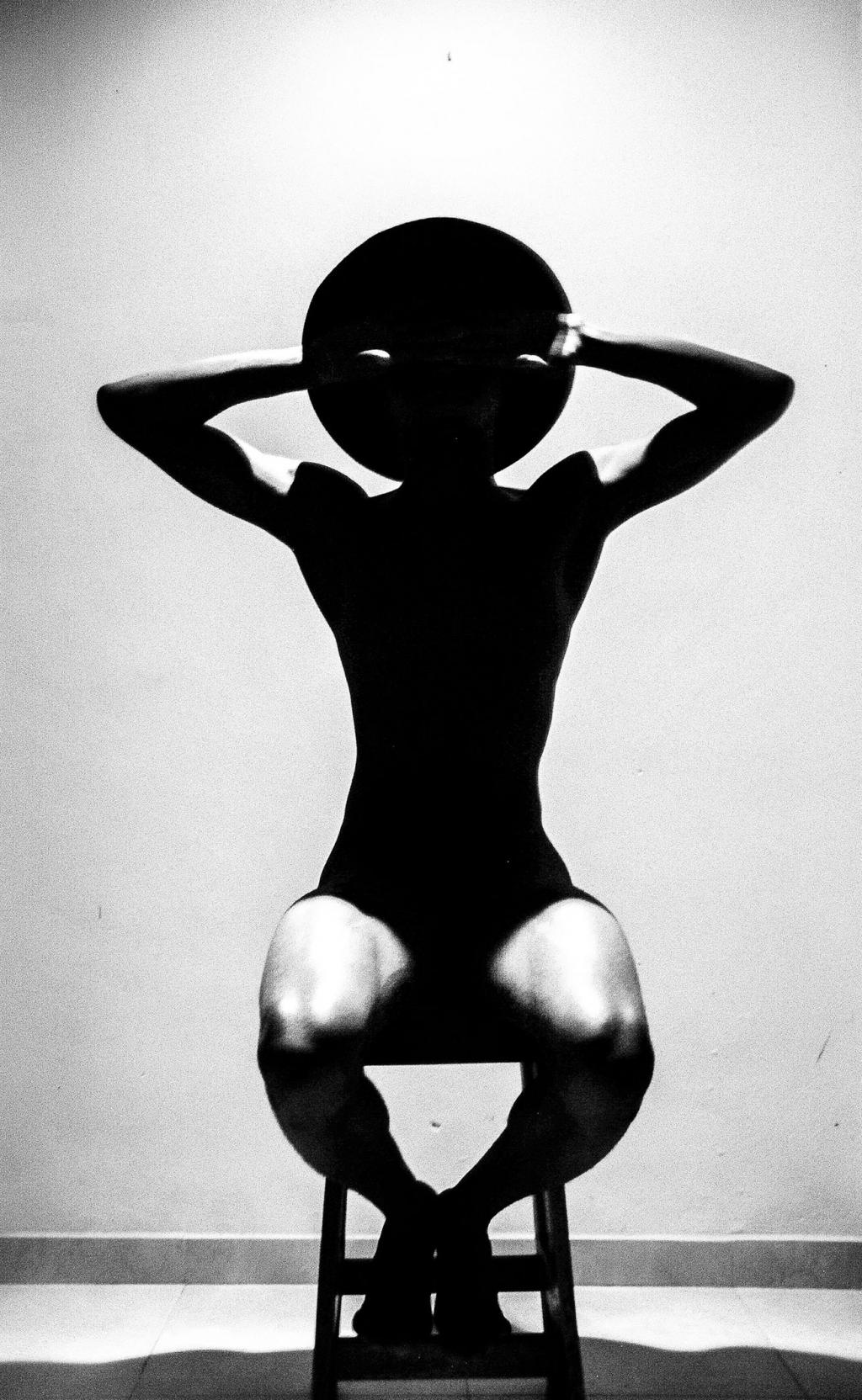

Ferreira’s works “traces the resonance and impact of colonialism and post colonialism in contemporary societies” (JAG. 2017) through her use of stark lines that create her forms. On the walls of the exhibition feature drawings of buildings and their structural outlines, presenting the viewer with deconstructed images of buildings to their simplest forms. Her installations are made from wooden poles, concrete and plastic tubes used for plumbing. Miniature concrete foundations are connected to cement brick and corrugated steel. The viewer is left to figure out whether Ferreira is in the process of creating the structure or has begun dismantling the final product.

Her works reflect the moment of tension that comes with the destabilization caused by change. Colonialism has ended yet its fragments remain. There is a beauty to these structures but they came at a cost to our very own collective humanity.

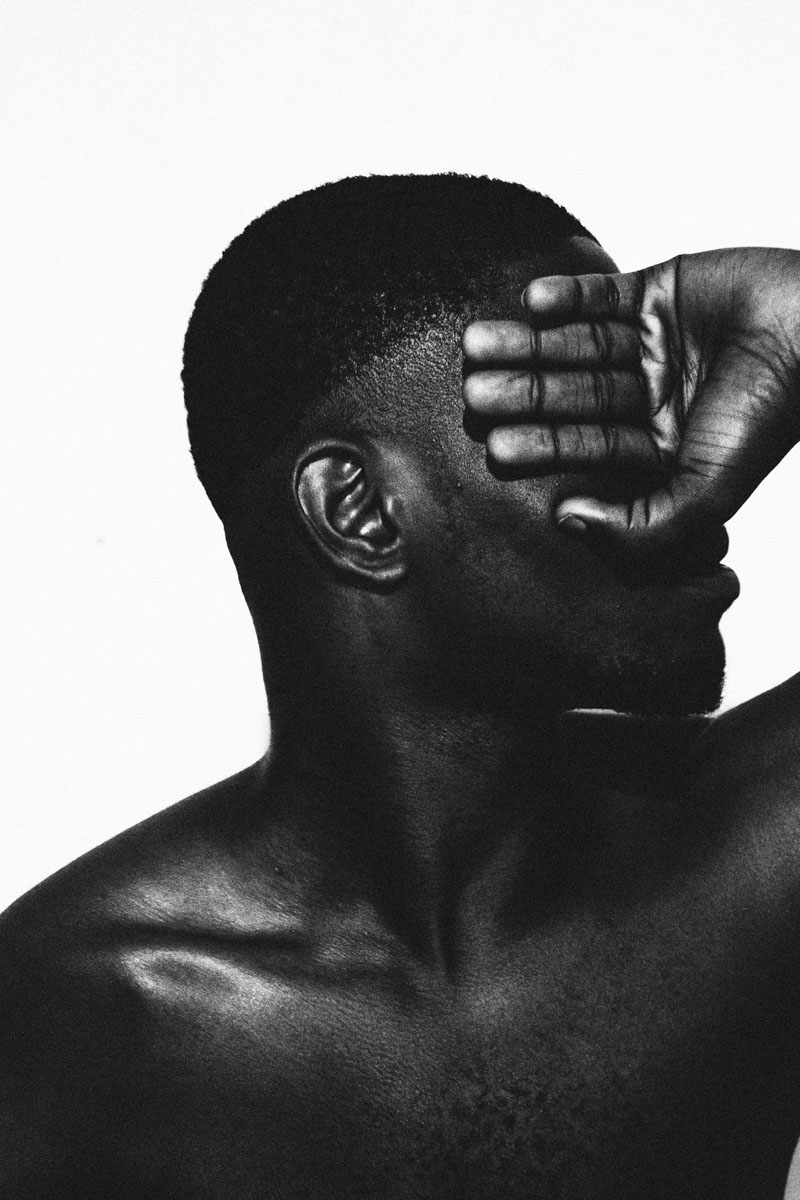

Yet the very issue also applies to the conceptual gaps between the body of work and those understood as being its ‘maker’. We see human form in her photographs of the construction of the JAG. Bodies are depicted as shadows amongst buildings. She features photographs of the building during the museum’s recent renovations. The builders are distant figures in the background in a spectral haze.

What Ferreira seeks to challenge seems to be perpetuated in these very works. The black body remains separate from the works. Only the names of the architects is revealed and the labor of those who built the walls go unrecognized. We see a woman building a hut yet we do not see the faces of those who made the concrete walls.

Ângela Ferreira, Maison Tropicale (footprints), (2007), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 (1)

Ângela Ferreira, Maison Tropicale (footprints), (2007), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 (1)

The challenge to this history will be one that critiques the very relationship where black bodies are reduced to viewers or consumers and not the actual producers. We remember the names of the architects and salute their work yet no attention is given to the other forms of labor.

The very line fenced between the JAG and the Joubert Park continues in her works as we are not made aware of who actually made the buildings and their labor made a non-factor. We need to begin to reimagine how we speak about our current buildings in South Africa. Questions need to be asked over whose names get associated with the buildings.

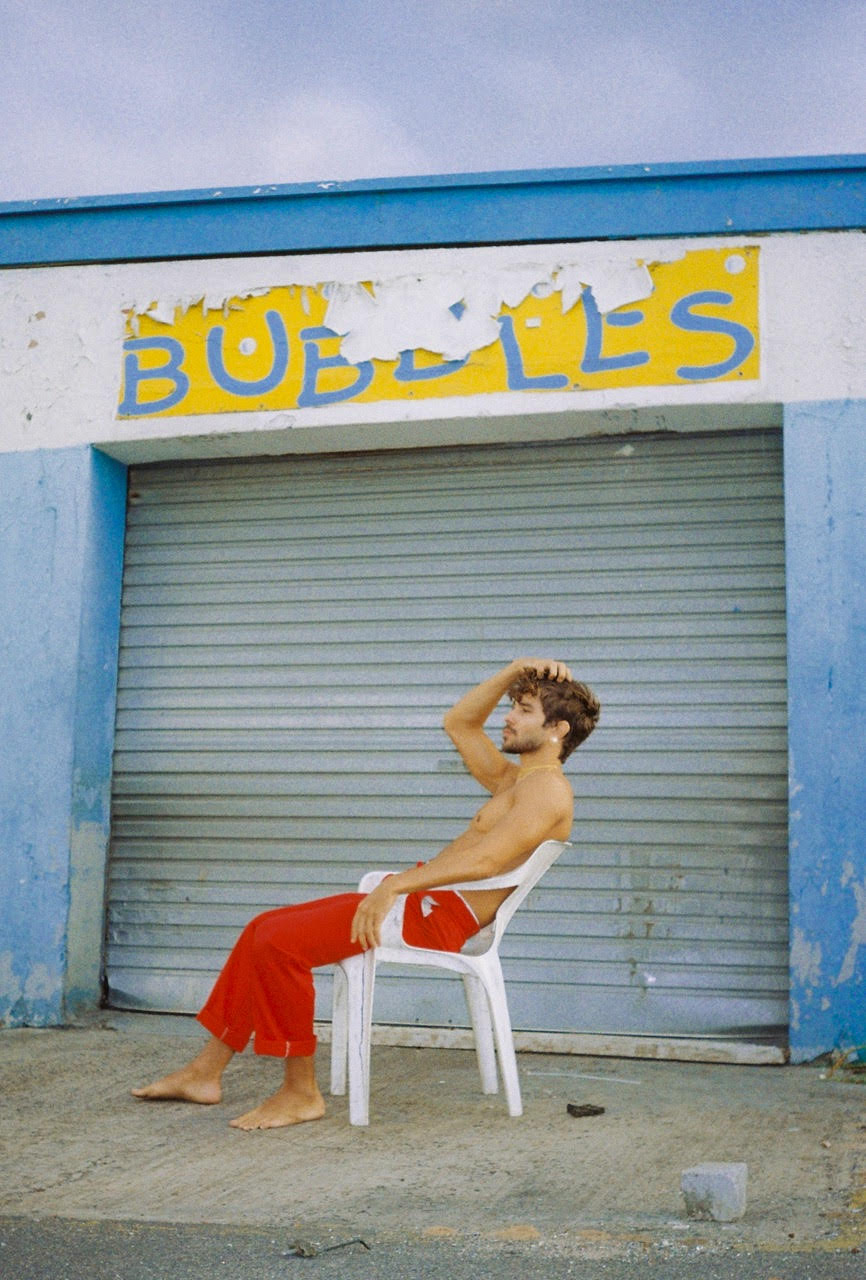

Yet for the artists we are called upon engage with such a past through our consumption of its works. “Buildings contain history… But mostly for me they are also sculptural. They are designed for a function but architects also have an aesthetic program in mind. So I see them as public sculptural interventions. We all judge them all the time. They inhabit our daily lives and we are entitled to comment on them.”

Watson discusses how “ there is an interesting parallel between the structural failures and the intellectual limitations of museums, South Facing represents a response …. on these urgent questions”. Through these works the viewer has the opportunity to question how we go about filling the gaps. As consumers of public art we are forced us to engage with ideas over who gets chosen to represent the ‘achievement’ of a civilization.

Ângela Ferreira, Double Sided, (1996-2003), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Double Sided, (1996-2003), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Werdmuller Centre, (2010), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Werdmuller Centre, (2010), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Remining (Mine building), (2017) Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Remining (Mine building), (2017) Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Maison Tropicale (footprints), (2007), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 (1)

Ângela Ferreira, Maison Tropicale (footprints), (2007), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 (1) Ângela Ferreira, Double Sided, (1996-2003), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Double Sided, (1996-2003), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 Ângela Ferreira, Werdmuller Centre, (2010), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Werdmuller Centre, (2010), Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017 Ângela Ferreira, Remining (Mine building), (2017) Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017

Ângela Ferreira, Remining (Mine building), (2017) Installation view South Facing, Johannesburg Art Gallery, 2017