An anonymity of objects, each with an individual history. Tussled and turned. Transformed by the rhythm of a pulsing river. Caked in the sand of the bank. Reaching the shores of the sea, washed up and waiting. Tentatively collected and contemplated. Repurposed. Filled up in phallic form. Residue. Residual waste reimagined.

Abri de Swardt’s latest solo exhibition at Pool, Ridder Thirst, presents a temporal slice of a queer historiography rooted within the context of Stellenbosch and its university. He describes how this form of research and making integrates histories that are, “closer to the skin and intimacy…introducing a body that is otherwise occluded from that site.” This multi-media body of work spans the complexities of youth and questions of collective agency. Through his practice, Abri investigates notions of disassociation, disidentification and desire as political positions.

The beginning of this project can be traced back five years to Abri’s investigation into how the Stellenbosch Visual Art Department started in 1964. When founded, the department was intended to be rooted in Eurocentrism and an extension of the Western canon through an emulation of the Bauhaus. During this research Abri stumbled across the work of Alice Mertens, who was appointed as the first lecturer in photography. Most well known for her ethnographic photo-book African Elegance (1973), she also published a book, Stellenbosch (1966, republished and expanded 1979), which captured couples in leisure on the banks of the Eerste River in Stellenbosch. As a document of the town under Apartheid, Abri was interested in the depictions of the students in nature, and the representation of heterosexual relationships mimicking the ‘neutrality’ of photography. In Mertens’ photographs, linkages can be made between white entitlement over land in relation to student bodies.

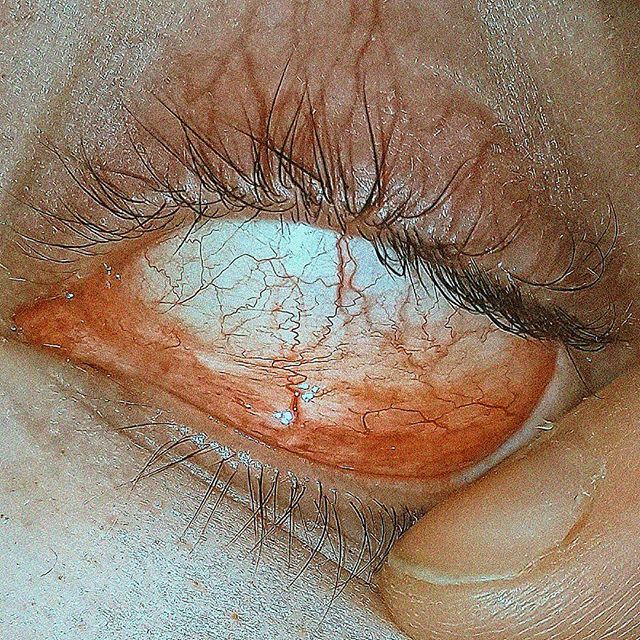

His film, Ridder Thirst (2015-2018) starts in a darkroom depicting one of Abri’s former lecturers, Hentie van der Merwe, who was a key figure in 1990’s South African queer visuality. He appears to be developing and solarizing Mertens’ images. The photographic matter slowly starts to seep into the paper. Through the narration of the scene, the audience is introduced to The Shadow Prince – a fictionalized figure driving the narrative, said to have escaped from a camera and into reality. “A lot of my work deals with the limits of photography and how collage always treats photographic material as sculptural material.” The process of his work draws attention to the physicality of the photograph. Digital collage features in the film as motion-tracked media floats down the river in the form of oak leaves, stock embelms reminiscent of camouflage and university branding.

Settler colonial whiteness is positioned at the intersection between the sea and the river – the site at which people historically landed on the beach. The whole narrative of the film is based on rolling-up the First River and burying it in the mountain- highlighting geographic and historical tensions. The name of the film and exhibition Ridder Thirst was formulated through a combination of Afrikaans and English. Ridder is Afrikaans for ‘knight’ whereas thirst evokes notions of desire (being thirsty), while also, in an onomatopoeic play on ‘river first’, referencing the river which is central to the project. Abri describes how the combination of words articulates a medieval desire for a heroic figure something that he says is displaced and “unfulfilled in the film.”

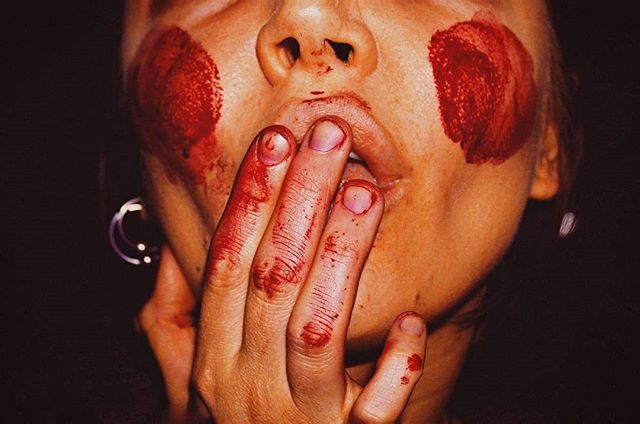

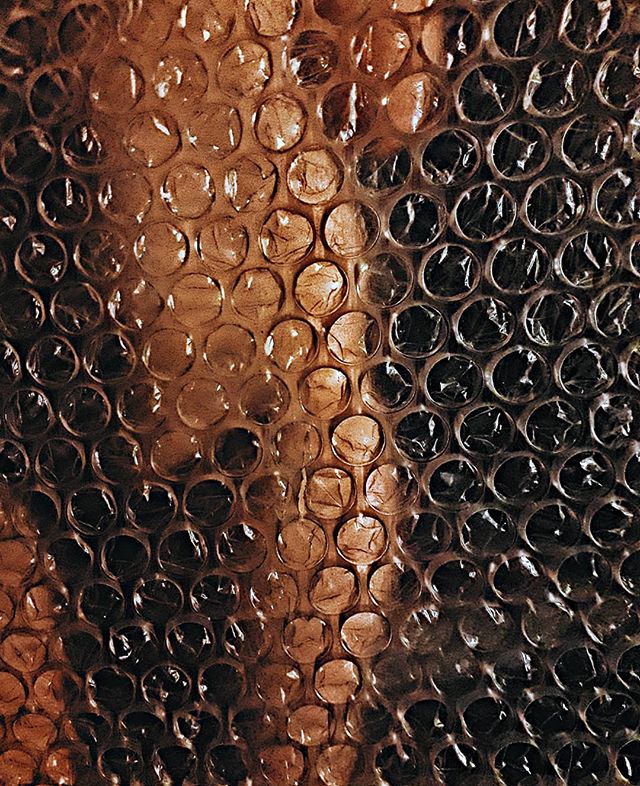

Eerste Waterval (2018) is a piece that explores the origin of the river. An assortment of objects was carefully collected at the mouth of the river and inserted into an elongated clear plastic bag, a condom of sorts. “It becomes the actual trace of the run of the river.”Organic matter and plastic merges from Stellenbosch and Macassar, where the mouth of the river lies – geographically adjacent but “racially and economically disparate spaces.” Abri described how materials would lose their shape and become entwined with other objects from the river bed. “It’s really sculpted by the river.” He also mentioned how “garbage is also a kind of collaging of usage and time” which relates to other aspects of his work that draw from expanded notions of archeology and mapping.

The double 12” vinyl record Ridder Thirst LP (2016 -18) is another integral element of the exhibition. Abri wanted to generate a platform that included a spectrum of voices which thematically responded to the concepts in his work. The sonic forum also stemmed from a series of reading events that took place in Johannesburg and Cape Town – prefacing and speaking to the historical ruptures of the Fallist Movements. “I invited other people who were with me at Stellenbosch at the time,who were also working with writing and voice in their practice” Abri was interested in creating a broader conversation and shifting the focus to the shared,“closeness of people listening to each other” in various modes of address. The work includes tracks by, Stephané E. Conradie, Metodeen Tegniek, Athi Mongezeleli Joja, Pierre Fouché, Khanyisile Mbongwa, Rachel Collet, Alida Eloff and Abri de Swardt. There will be a listening event playing the 62 minutes of the record next month as part of.the exhibition’s public programming. Ridder Thirst runs until the 17th of June at POOL in New Doornfontein.