In a post-apocalyptic Ethiopian landscape, where Michael Jordan is enshrined, masked Nazi-clad bandits steal Ninja-turtle amulets, and witches trade in Michael Jackson records, we meet Birdy and Candy.

As a rusted spaceship hovers in the sky, and a defunct bowling ball machine returns to life, Candy embarks on a quest to find Santa Claus. As he follows the wrangled train tracks to an unnamed city, he meets hauntingly strange characters in desolate places. Birdy stays at home, tormented by bad dreams and unsettling sounds.

A reel film of Superman has been playing for forty years, and a caged lion shows the way. In a film that could easily become garish and absurd, Spanish director Miguel Llanso, based in Addis Ababa, delivers a profound and whimsical work. Daniel Tadesse (Candy) takes us on (anti) adventure, one that defies the Hollywood science fiction convention of spectacle. There will be no CGI (computer generated images), not a gunshot, no army of soldiers, not even a computer. At only just over an hour, Llanso has completed his task. The viewer is left with both a sense of emptiness, and fulfilment. Is this a movie about hope, about love, about companionship in adversity? What do we treasure when we navigate the wreckage that is our earth?

The film Crumbs was released in 2015 and filmed in the Ethiopian ghost town of Dallol. Films like these are a celebration of African excellence and skill – and as Five Fingers for Marseilles graces our cinemas, it becomes apparent that African cinema is beginning to transcend and redefine its boundaries.

Closer to home we have Sweetheart directed by Phat Motel. The sparse Karoo landscape juxtaposes the abandoned cityscape, a husband and child lost, a desperate wife seeking her family. We see all too familiar aesthetics, reminiscent of Blade Runner and Intersteller. Sometimes still we see I am Legend or the Wizard of Oz, as we traverse the rural countryside, and find our way to the hostile, decaying city.

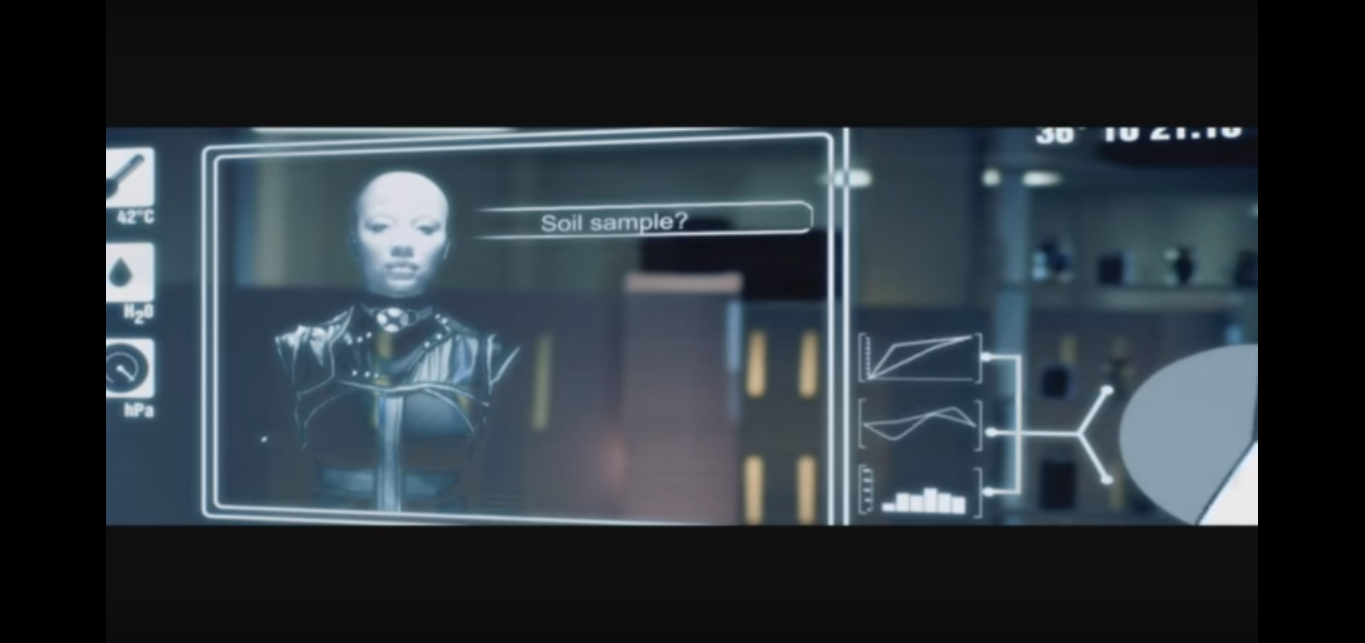

We return to East Africa, where after the Water War, World War III, we meet Asha, asleep at her desk, dreaming of a tree. A computer buzzes “Dream detected – take dream suppressant pills.” She takes a tablet.

Asha stands, walks past grey-clad figures working out. Kinetic energy – 0% pollution, a sign reads. We find Asha in a queue, a barcode on her arm is scanned, and she receives her pitiful water allowance. In this post-apocalyptic short film directed by Kenyan Wanuri Kahiu, we see a futuristic ‘East Africa’, most likely Kenya, that competes with any Western science fiction thriller. Pumzi, which means breathe in Swahili, manages in just 25 minutes to make us consider the greed and egotism of a world divided by resources, the power of bureaucracy, the importance of survival.

While Black Panther celebrates the superhero, the Marvel-clad wonder, these African directors consider a subtler hero. A hero confronted with the challenges of sparsity, of isolation, of decay and desolation. These are films that embrace silence. As we begin to consider what makes an African hero, and what an African futurism looks like, we need to consider whether there really is a Wakanda, or if heroism comes from those who face adversity in an ‘Africa’ closer to home.

Often, we forget of the innovation in film coming from our own country and continent, and this is partially but not exclusively because of lack of access. We need to stop District 9 becoming the archetypal ‘African’ sci fi movie and celebrate the diversity of our own industries. Perhaps it is time for a African Science Fiction Film Fest – because now, more than ever, we should salute the African hero.