“When books are scarce, people are knowledge”

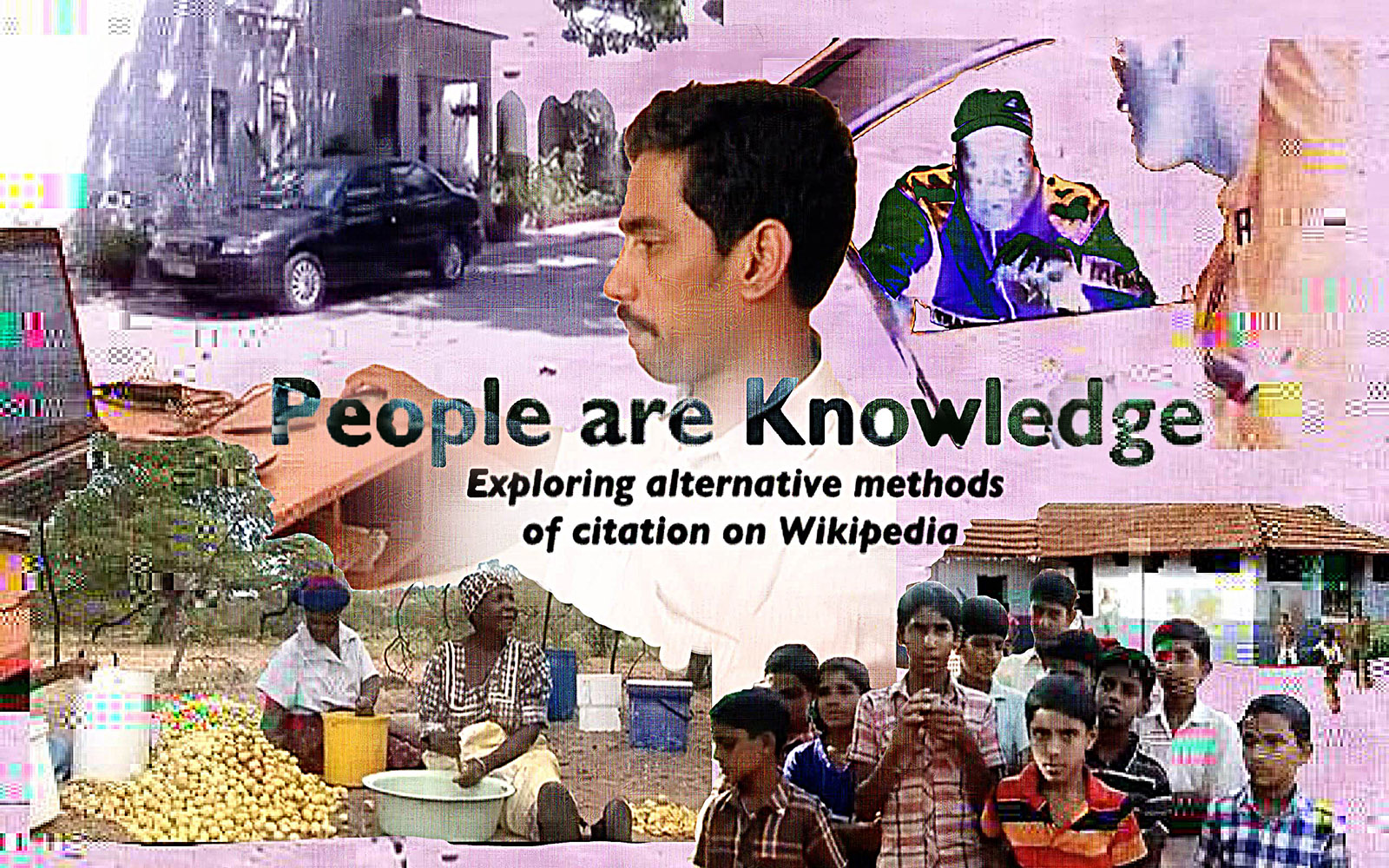

This is a quote from an email interview I had with Bangalore-based writer and activist Achal Prabhala. It is an introduction to the thinking behind the Oral Citations Project – a project he was involved in which explored alternative methods of citation for Wikipedia and ways to redefine who or what is understood to be a knowledge source.

As a writer, the majority of his work focuses on race and pop culture. However what ties his writing together is his accumulated work in small publications, which he describes as “beautiful, odd magazines” in our exchanges via email. These include Bidoun, Chimurenga, Transition and African Is A Country. As an activist, he currently works on increasing access to medicines for life-threatening conditions like AIDS, cancer and Hepatitis C in India, Brazil and South Africa.

The Oral Citations Project aimed to bring the periphery to the centre, and simultaneously expand on the way in which knowledge is defined. However, before unpacking the project it is necessary to contextualize its presence.

Wikipedia has been criticized as a site for reflecting a Western, male-dominated mindset. This is translated into the way in which knowledge sources used for Wikipedia articles are framed, mimicking the old encyclopedias it is supposed to replace. Some critics have stressed the tradition of footnotes and sourced articles as references and citations needs to be re-thought. This is relevant as there is an abundance of knowledge that exists outside of books and the internet that cannot be present on Wikipedia because it cannot be sourced and referenced within the package that Wikipedia requires. Following on from this critique, Achal, who was an adviser to the Wikimedia Foundation at the time of the project, embarked on unpicking this policy and finding a way to present information that did not fit into that mould. This resulted in a short film titled “People are Knowledge“, which demonstrated how much knowledge is lost due to Wikipedia’s citation and verification policy, as well as provided an opening to be able to allow the site to be more inclusive of other knowledge sources.

The project was planned with three Wikipedia languages in mind – Malayalam, Hindi and Sepedi – and took place across various places in South Africa and India. It involved interviews with academics and ordinary people to document everyday practices that had not been shared on Wikipedia before due to the limitations mentioned above.

I had an interview with Achal to find out more about the project and if it has assisted in expanding Wikipedia’s knowledge base.

When conducting interviews, how did you explain what Wikipedia is to the people who had never heard of the site before?

This is a great question. Let me start by explaining who we interviewed and how. I interviewed people along with Wikipedians who knew them; for instance, in South Africa, we interviewed people in Ga-Sebotlane, a remote rural location in Limpopo, and I was guided by Mohau Monaledi, who lives in Pretoria, but is from Limpopo, and speaks Sepedi. Mohau is a prolific Wikipedian, and founded the Northern Sotho Wikipedia project, which is now a little gem of the Internet: it went from 500 articles in 2011 to over 8000 currently. It is the largest South African Wikipedia after Afrikaans. I was one of the people who helped get it off the ground, and I’m enormously proud of where it is today, way ahead of larger language groups in the country like Zulu, and even on the continent, like Igbo.

The people we spoke to were working women who were fluent in Sepedi, but not English. They were women who worked in their houses and on the land, and had been doing it for years. Cellphones were common, but none of them had heard of Wikipedia. So, we explained what we were doing, explained what Wikipedia was, and why we wanted to talk to them. They got it immediately. It’s important to note that we weren’t asking the women we interviewed to part with family secrets or private historical memories: we were talking to them about how they prepared Mokgope (a fermented drink made with Marula fruit), and how they played popular village games such as Kgati and Tshere-tshere. In other words, we were interested in bringing everyday aspects of their lives to Wikipedia, and they liked the idea.

How do you explain the importance of documenting everyday practices to the people you interviewed who fell outside of the academic space? What were their reactions?

I will confess, wherever we went – from Limpopo in South Africa, to Kerala and Haryana in India – we were met with enthusiasm, but also puzzlement. A number of people I met in Ga-Sebotlane and Thrissur were just flat-out amused that anyone would be interested in documenting the most mundane aspects of their existence. I am almost as much a foreigner in rural India as in rural South Africa, and I suspect they thought of me as some crazy guy who had to be indulged. But once we started asking questions, and they could see our intent was serious, I think they were quite thrilled that someone was showing interest. It’s been beaten into our heads that we have a lot to learn from Professor Humdrum at Harvard, but not so much from Ms Moremi in the field under the Marula tree in Limpopo. And by us I mean not just you and me, but also the people under the Marula tree.

Speaking for myself, the moment I flipped that ridiculous assumption within my own head, and treated the people I was talking to as important people with important things to say, they saw themselves that way as well. The mere act of listening made it easy for people to see themselves as repositories of knowledge – and this switch was a joy to watch, like a light being turned on.

Unpack the importance of inserting underrepresented people, practices and languages online, particularly on a site associated with the collation of knowledge sources such as Wikipedia?

The answer to this question is important. The answer also makes me furious, so I’ll take a deep breath first.

All right. Let’s take what we did in Limpopo. We created articles, based on our conversations with people, on Mokgope, Kgati, and Tshere-tshere. Until that point, these things did not exist as public knowledge on the internet, even as they had existed for decades as public knowledge in everyday life. Millions, if not all South Africans, know exactly what these things are. Let us consider their equivalents in France: Pastis (which should be a human rights violation) has a detailed Wikipedia article in 22 languages; Pétanque has a detailed Wikipedia article in 41 languages; Boules has a detailed Wikipedia article in 31 languages.

At this time, because of the project we ran, Sepedi Wikipedia has one article each on Morula, Kgati and Tshere-tshere. Detailed articles, with interviews as citations, and pictures to go with words. No knowledge of these three things, however, exists in any other language; the articles have not been translated. Arguably, no one who speaks Sepedi needs reminding what Morula is. Just as, arguably, the English world would be expanded by a formal understanding of what Morula is. But that hasn’t happened, because English Wikipedia deems Sepedi knowledge unworthy, as well as suspect – since in the case of these three articles, it isn’t based on something published in a book – and we’ve given up holding our breath.

France has 66 million people. South Africa has 56 million people. Person for person, they’re not that different. On Wikipedia, however, they’re worlds apart. One is a country with Human Beings who Know Things; the other is not. I recounted my experience of documenting village games in India and South Africa to a German scholar.

He jokingly said, if these were village games in Germany, they would each be given a 7-volume manual to accompany them, and would have become Olympic sports by now. I laughed, but it’s true. I don’t think Mokgope, Kgati or Tshere-tshere are any less real because there’s no record of them in books or the Internet, or because Europeans have no idea what they are. But the legitimation, transmission and circulation of knowledge holds a unique power in the world: the power of universality, the power to render holders of that knowledge fully, equally and undeniably human.

By far the most tiresome aspect of conducting the exercise was explaining it to Wikipedians. I had some really strange conversations on public mailing lists. The prevailing view on Wikipedia was best expressed by a German historian resident in the Netherlands called Ziko van Dijk. I explained my project. He replied with the condescension of a schoolteacher scolding a naughty child, and asked me to leave history to the historians. I tried to point out that documenting one beverage and two village games in Limpopo hardly constituted messing with history. He did not budge; he remained adamant that my secret agenda was to infect Wikipedia with mythological juju. He kept at it for years, advocating increasingly bizarre theories, such as that recognising oral traditions would, somehow, allow him to claim to be a descendant of Charlemagne. (For good measure, he also threw in an inexplicable incident about “a territory in Africa, occupied by the British” where some King was maybe thought to have had seven sons, and then maybe thought to have had only five, which was, in his view, conclusive proof that you must never trust anyone without a PhD in history).

Unpack the title for the project and the film, People are Knowledge?

When books are scarce, people are knowledge.

I don’t think of this as a problem. It’s simply a fact. It would be nice to have more books, sure. But, as Geetha Narayanan says in the film, “Coming from a culture where so little is written down, do we then say we know nothing?” The assumption that people who don’t have books are dumb, is plainly preposterous. In the course of rearranging our ideas about books, knowledge and stupidity, however, there are some underlying conditions to consider.

One: Rich countries produce plenty of books, poor countries do not. Every year, the UK produces 1 new book for every 300 people. In South Africa, however, the figure is 1 new book for every 7000 people, and in India, even worse, at 1 new book for every 11000 people. In historical absolutes, the number of books produced in the US and Europe outstrips every other country in the world. What this means is that the knowledge of South Africa and India is not in books.

Two: Even when local books exist in poor countries, they’re inaccessible. Public library networks are weak, digitization and electronic access is almost non-existent, with the effect that if you live in a country like India and South Africa, and want to reference an existing book, it is frequently not available to you.

Three: Even when there is media – books, periodicals, journals, newspapers – to cite, if the media comes from a country outside the US and Europe, it is suspect, at least on Wikipedia. Countries like South Africa and India may have huge newspapers that cater to millions of readers, but Wikipedia refuses to accept that something happened unless it happened in the New York Times. The most famous instance of this bias is with the fictional Kenyan phenomenon called Makmende, which, despite being written up in The Daily Nation and The Standard, two respected Kenyan newspapers with gigantic readerships, was refused a Wikipedia entry until the story merited a mention in a ‘real’ paper, the Wall Street Journal. We’re told the way to play the game is to catch up. Write more! Publish more! Then, when we do that, we’re told, umm hold on: that’s not good enough. Because, of course, nothing really happens unless it happens in a journal published out of Cambridge or a newspaper in Manhattan. And Wikipedia is passionately committed to this warped, outmoded, colonial view of the world. Instead of playing the imitation game, I thought, why not turn the tables?

On your project site, I read the argument that Wikipedia does not take advantage of “internet objects”. Can you share why this is an important statement when thinking about expanding citations on Wikipedia?

Wikipedia is a publisher on the Internet, but it is deeply suspicious of the Internet. This is a fundamental fault line, and it is already fracturing Wikipedia. When you have a new system of publishing, one that is non-profit, public, and supposedly revolutionary, a system that was made by the Internet and that could only exist on the Internet and moreover, relies on the anonymous labour of crowds to work, in that case, to exclusively rely on words printed on paper for authority is ludicrous.

Wikipedia is an open platform that is made entirely by user contributions. But it disallows citations from IMDB (the Internet Movie Database) and classifies it as an unreliable source, because, wait for it, IMDB is an open platform that is made entirely by user contributions.

In the early years of Wikipedia, in 2005, Jimmy Wales (the founder of Wikipedia) was fond of saying “We help the Internet not suck.” That was then, before blogging became legit, before the smartphone was invented, before social media took over our lives. Now, in 2018, thanks to the combined force of cheap data, cheap Android phones and social media, we have infinite choices. There are many ways in which social media sucks, but one way it definitely does not is in being a fairly democratic global force in which anyone can participate.

In 2005, Wikipedia was pitched in a fierce battle for legitimacy against the print edition of Encyclopedia Britannica, and it was arguably better than anything on the Internet. In 2018, Britannica is dead, Wikipedia reigns supreme, and, I would argue, it has become considerably less democratic, less open, less global, less diverse and less inclusive than anything else on the Internet. Everything on Wikipedia says 2001, especially its deliberately maddening interface, but nothing says ‘hello yesterday!’ as much as its refusal to treat the Internet as a place of knowledge, or its refusal to learn the one useful lesson social media can teach us, which is that projects prosper by inviting people in, not by keeping most of the world out. Let me put this more simply. If I wish to learn about French food, which I can’t eat, because I’m lactose intolerant, I’ll go to Wikipedia, but if I wish to learn about South Indian cuisine, which I can eat, and love, I’ll go to YouTube.

In a New York Times article on your project, you mention that publishing is a system of power. Could you please unpack this, and how this fits into the foundation for People are Knowledge?

I’m from Bangalore, in India. I studied in the US, but haven’t worked there. The only countries I have lived and worked in outside my home are South Africa and Brazil. Currently, my work is spread across Bangalore, Johannesburg and Rio de Janeiro. So I know what unequal geography looks like, and I am intimately aware of how colonialism lingers in the mind long after it’s officially gone. I knew a whole lot about Manhattan before I stepped foot in it; I knew very little of Johannesburg before I got there. I knew that words said in London were meaningful; I knew that words said in Bangalore were kind of meaningless.

One of the nice things about becoming an adult was becoming confident enough to challenge this idiocy. And because the Internet existed when I grew up, and especially because Wikipedia existed, I believed, naively, that this was our great opportunity to rewrite the world. Let’s face it: we will never catch up with the accumulated mass of formal knowledge produced by Europe and the US. Not going to happen.But in the digital world? I did think it was the one place where we could have a kind of equality; new rules for a new world. Every movement in the last 20 years signaled that equality was near: the invention of Wikipedia, the drop in telecom prices, the proliferation of cheap Chinese smart phones, the millions of people coming online in places like India, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa.

And yet, it did not work out that way. Publishing has always been about power.

In the 14th century, you could be killed for translating the Bible into languages people actually spoke. In the 15th century, the printing press gave rise to new anxieties, and for several centuries thereafter, printers in Europe were only permitted to operate with the approval of their monarchs. Things may seem to be completely different now, but a deep dive into the political economy of the book will make it clear we are still operating with a command-and-control version of knowledge. The colony may have come and gone, but knowledge remains a thing produced in the centre – and consumed in the periphery.

Wikipedia’s lamentable dependency on the book, continuing in this long, grand, and incredibly racist European tradition, is why we in the periphery are avid consumers of Wikipedia, but not producers. Publishing is a system of power, and so is Wikipedia. You look at Wikipedia, and think, hey, it’s on the Internet, it’s made by volunteers, it’s got pop singers and porn stars, anyone can contribute, it must be revolutionary. But don’t be fooled: it’s merely the old system of power, wrapped in a dazzling gauze of technological emancipation and repackaged with a benevolent liberal bow. Don’t take my word for it. Instead, take just one of Wikipedia’s own published statistics: there are more producers of Wikipedia in the Netherlands (population 17 million) than the entire continent of Africa (population 1.2 billion).

Are you still connected to the Wikimedia Foundation?

I’m not. I served on the Advisory Board of the Wikimedia Foundation from 2006 to 2018. I quit, or more accurately, I certainly quit a board that I’m not certain exists, since the Advisory Board has been in a Kafkaesque limbo for some years. I did some good during my term, as well as some things that did not turn out well. I’m proud of helping start the South African chapter, which is flourishing, and not so proud of helping the Indian chapter come into existence, since it blew up in a hot cloud of incompetence and ineptitude. I played a part in pushing for the Wikimedia Foundation to directly intervene in stimulating producers in India, Brazil, and the Middle East, and I’m glad to have played an early role in pushing the Wikimedia movement to recognize affiliations from broad groups of people, like Catalan speakers, not just those from sovereign states.

In the end, however, as a result of my work in India, and especially as a result of my work on oral citations, the trolling and harassment from other Wikipedians simply became too much. The hostility was insane: every discussion, every interaction online, was toxic. At the same time, the Wikimedia Foundation decided it had not much use for me. I’m not sure which was worse, being attacked by the community, or being ignored by the Foundation 🙂 Either way, I knew it was time to go.

How has Wikipedia’s citation policy/strategy changed since the conceptualization of this project?

The short answer is not one bit. In fact, it’s moved in the other direction, with the rules becoming even tighter. Wikipedia is now unapologetically hostile. If you came to Wikipedia in 2001 and put in some text, it would stay, as long as it was reasonable, and other Wikipedians would work with you to improve it, by adding citations and so on. Try that today, and you’ll be shut down immediately, then flamed, and then shamed into never contributing again. Every new contributor is essentially treated as a hostile vandal or a paid public relations agent until proven otherwise. Of course, it doesn’t help that many new contributors are, indeed, hostile vandals and paid public relations agents. It’s an impossible problem, and the encyclopedia anyone can contribute to has made no attempts to solve it, save for aiming a giant blowtorch at anyone who tries to contribute.

But it’s not all bad. A few good things came out of the oral citations project. The first is a set of independent initiatives that sprung up, to work along similar lines. Peter Gallert, an academic in Namibia, is working on a project to bring indigenous knowledge to Wikipedia. In San Francisco, Anasuya Sengupta, Siko Bouterse and Adele Vrana, three former Wikimedia Foundation staffers, have launched a grand and exciting initiative to remake Wikipedia. (One of their campaigns is to pry Wikipedia away from the hands of young men, and reverse the giant tide of sexism within; you can help them by contributing images of women to Wikipedia). The second nice thing is that the Wikimedia Foundation finally seems to have figured it out: a key plank in its new strategy is to “focus…efforts on the knowledge and communities that have been left out by structures of power and privilege.” Given that it’s the community that decides policy, not the Foundation, I’m curious to see where this goes.

How are you expanding on the project at the moment?

Having burnt only some of my bridges with Wikipedia so far, I’m now working on ways to burn all my bridges with the community. I’m kidding. Seriously, though, I’m writing a short account of being the brown guy in the ring. I think Wikipedia has got away with intolerable amounts of racism, sexism and hostility just because most people only see it from the outside, slot it as a ‘good thing’, and don’t ever find out about what is going on inside.

Having said all that, I should make a confession: I love Wikipedia. I loved it the moment I first saw it, and I’ll always love it. To me, Wikipedia is the public park of the Internet; a refuge from the relentless shopping-mall the Internet has turned into, the brave little non-profit in the oligopolistic dystopia that is our online landscape. When Wikipedia is good, it’s wonderful. When Wikipedians are good, they’re great. So I’m going to stick around for a bit, shout from the sidelines, and see if it has any effect. It’s ironic I spend so much time criticizing Wikipedia, because all I’ve ever wanted, really, is to be allowed inside. I’m not sure it’s entirely rational to want to enter a park run by confused white supremacists, but I’ve been going there for so long, I’ve become quite attached to it. Sure, Wikipedia is a racist, sexist and violent enterprise, but it’s my racist, sexist and violent enterprise, and I’ll figure out a way to deal with it.

Further reading:

A push to redefine knowledge at Wikipedia

Lifting the lid on a Wikipedia crisis

The Believer Interview with Achal Prabhala (The Believer)

Is Wikipedia woke?

We’re all connected now, so why is the Internet so white & western?