A few days ago American art critic and recent-Pulitzer Prize Winner Jerry Saltz published an article criticising the current art fair structure, the domination of mega-galleries, and highlighting the necessity for emerging, more “edgy” galleries. (So basically everything wrong with the art world). It’s good to know that these issues are being addressed on that level, but this isn’t a new critique. Having now introduced this debate, I’m not going to launch into a lengthy criticism ending with a passionate plea for change, but rather look at but one example of an arts platform doing things a little differently.

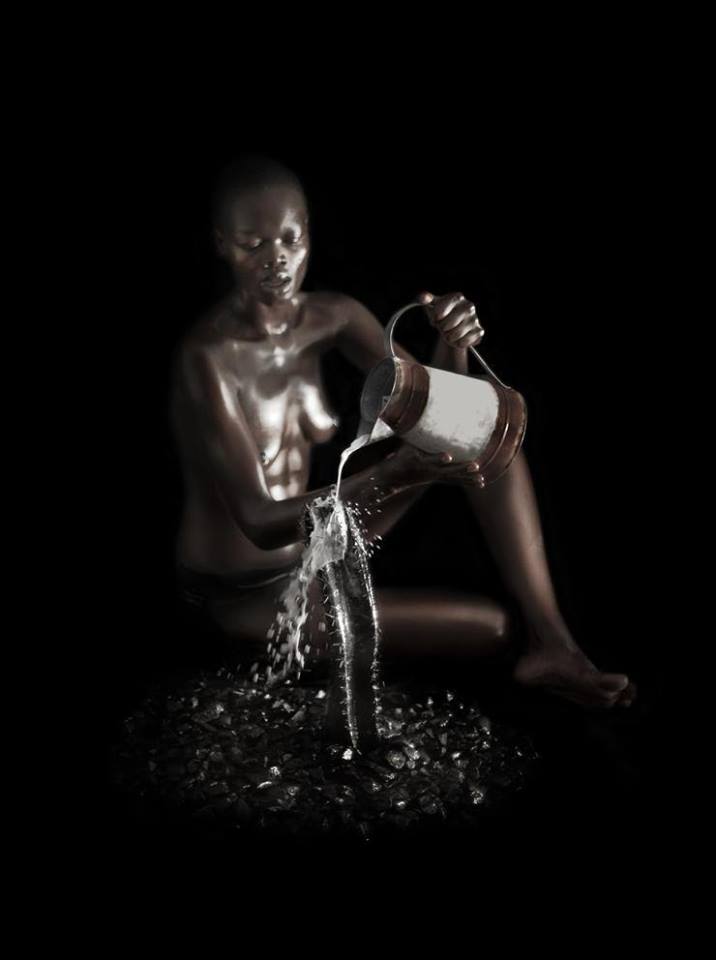

1.1 not only occupies a dynamic and category-evading space within the art world, but its inception was unconventional as well. Starting out of Deborah Joyce Holman’s studio, 1.1 began as an exhibition by Roberto Ronzani in October 2015. When asked about what inspired its conception, Deborah stated, “In the beginning, we were very interested in offering the space for very young artists, who in some way or another seemed to work with Social Media, or who we came across through Instagram, and who don’t necessarily situate themselves in the context of contemporary art, for example: a residency we did with Soto. Gang, a tattoo artist, or the Launch of three new Zines published by Popup Press. We always also put a strong emphasis on the space’s fluidity. It is important to define ourselves through the activities rather than formulating a very restrictive concept.”

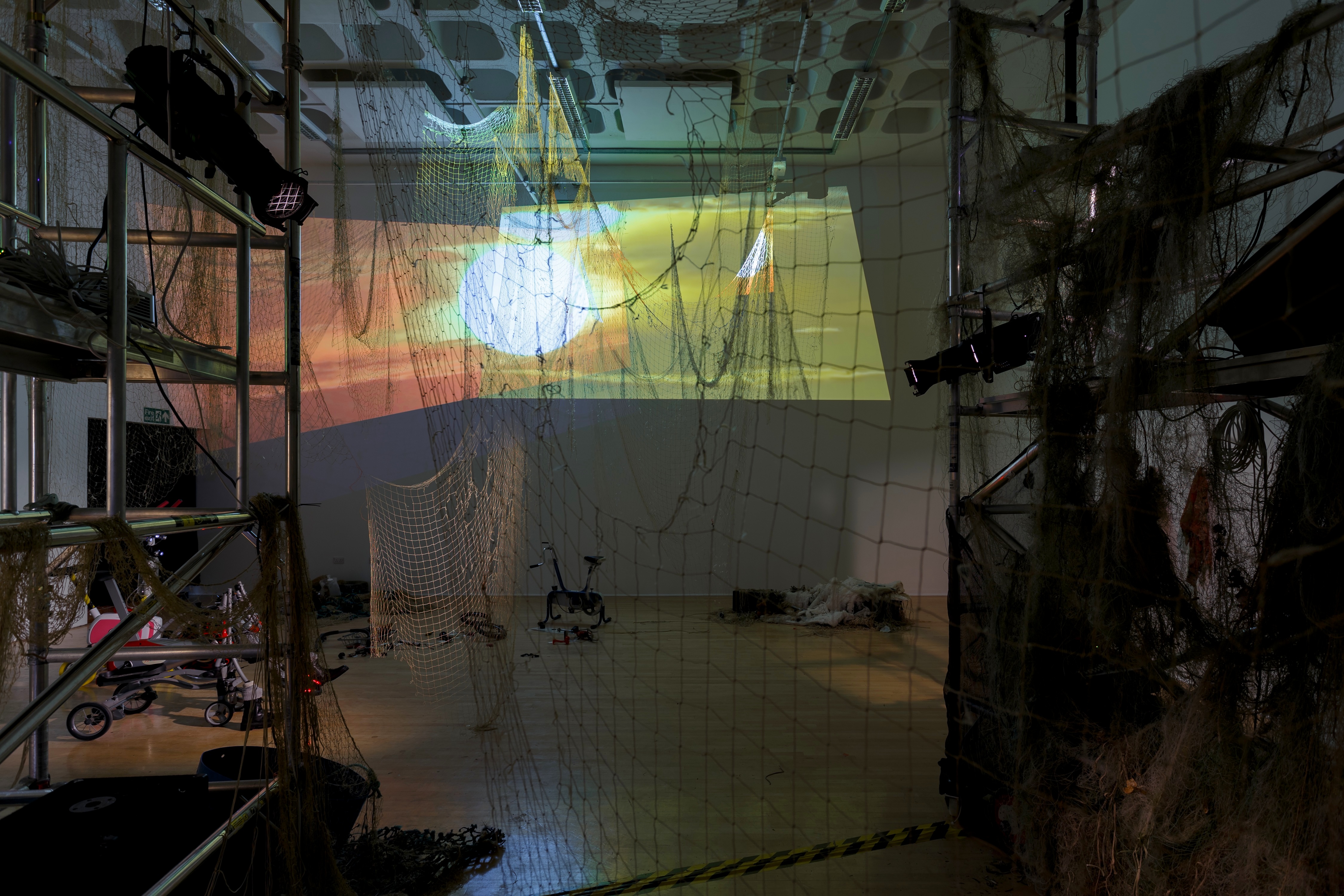

1.1 is different from a typical gallery structure as all their funding comes through grants and public institutions. This flexibility according to Deborah is counted as one of the space’s strengths, “as with 1.1 not depending on the art market and funding through sales, we have more liberty in our choice of artists, and in the media we show.” The idea that 1.1 functions more as a platform helps “to distance ourselves from the idea that all our activities happen in the exhibition space in Basel. The exhibitions are one very present part of our output, but it is not the only one. We also engage in the field of music, and organise concerts and other events in collaboration with venues across Switzerland and a few throughout Europe.”

As a platform, 1.1 places an emphasis on engaging young people in the arts, making it accessible to a broad public who may not have much knowledge of the arts. Deborah claims, “This can be very challenging, as it forces us to really look at how and where we promote events, shows, and where we aim for visibility of the space as itself. We use Instagram very heavily, as a sort of alternative exhibition space. This means, prior to exhibitions, the artists are free to use them as a residency, and it obviously allows to reach a whole other audience than those that are based in Basel and surroundings.” Funding is always another challenge that requires year by year evaluation.

As a platform with a passion for engaging new voices, Deborah and Tuula Rasmussen (who joined 1.1 recently) are always looking out for emerging artists with it being “a very intuitive process. It’s about keeping our eyes open, on Instagram and in more traditional ways, like through blogs, openings, our surroundings, etc. It has also happened a couple times that we were sent a portfolio or a recommendation and everything worked out to offer them a platform to show.”

It’s exciting that new art spaces are (seemingly) always opening up, but unfortunately it’s the case that while they begin as a challenge to existing institutions, inevitably they become institutions themselves. And so it was encouraging to hear from Deborah, as we ended off our email interview correspondence, that, “1.1 is in steady movement, and always changing, so we’re continuously re-evaluating everything and hoping to constantly adjust our values to the needs and demands of the artists, musicians and the public.”