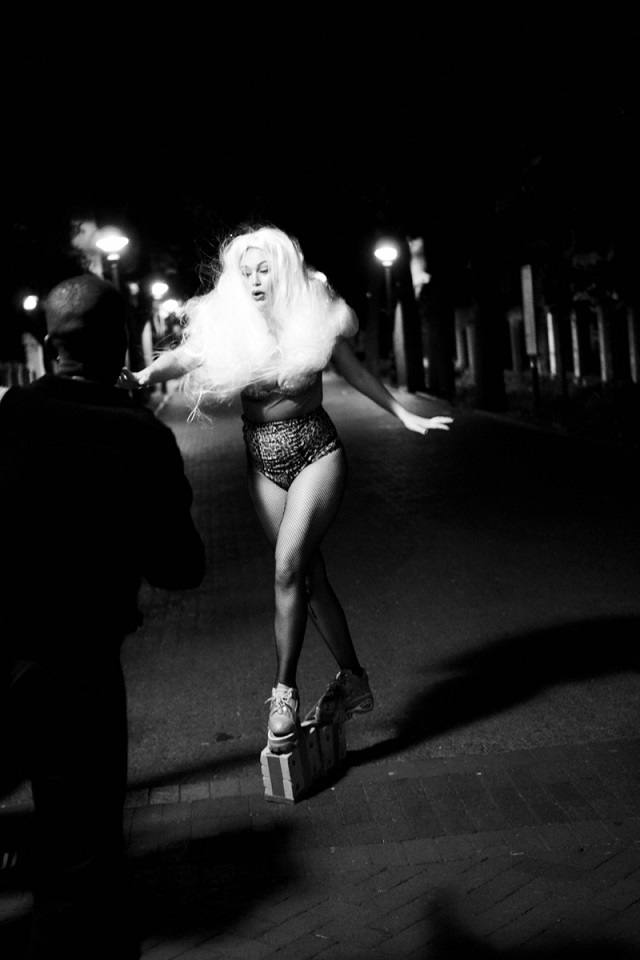

Jana Babez did a performance in the Company’s Garden with the aim of highlighting the tricks that womxn need to employ when navigating ‘public space’. The the trajectory of preparation, performance, and aftermath of the performance was documented by photographer Jonathan Kope and compiled into a photo essay. I interviewed Jana about this performance in relation to the increase in stories about womxn being abused, abducted and murdered in our country.

Tell our readers about how you like to describe your art practice? Some of your past performances appear to mirror the effects of the structural operations of patriarchal society as a way to highlight their absurdity. Would you like to elaborate on this?

I create characters, moments and parodies that mirror the beauty and terror of our lived experiences. I’m constantly trying to highlight the absurdity of the roles we are coerced into playing through exposing pre-existing power structures. My performances exist in a space between representation and parody. I create characters that on one level can be read as representative of women in society, but on another level have pushed identity production beyond what is deemed acceptable and are thus considered caricatures of themselves.

In my previous work, Miss Debutante, I created a calendar with a female character so drenched in nostalgia and hyper femininity that she can be described as a product of memory and toxic patriarchal society. My work puts female identity production and the complexities thereof front and centre. As Barbara Kruger famously illustrated for us, “Your body is a battlegroundâ€. Our bodies are the sites where wars over religion, sex and power play out.

In these times I think the role of performance artists is to confront the underbelly of our society head on. Our bodies are tools that can be wielded to enact political change. What makes the body such a powerful tool is that no one can take it away from you. They can try, but we bite back.

In the opening line in the write up for Nightfall you state that “Navigating space is never neutral”. I think this is such a powerful statement. Can you elaborate on the assumptions about space being neutral when people refer to a space as ‘public space’ and how this negates the “tricks” that womxn need to use to navigate ‘public space’?

Public spaces are often considered neutral spaces where all people can interact on a level playing field. This could not be further from the truth. Nightfall is an intervention where I aimed to challenge the neutrality of space and highlight the discord between how men and womxn experience public spaces. Company’s Garden is one of the most used public spaces in central Cape Town. It connects many different areas of the city, but as with many public spaces after nightfall it becomes more dangerous for womxn to navigate. This limits womxn’s ability to move between spaces thus restricting their ability to move freely. Public spaces enforce wider social prejudices. Nightfall at once challenges this discrimination by boldly placing a female body in a public space after dark, but also it highlights the dangers (potentially fatal) of womxn navigating public spaces.

I think it is also important that you mentioned that these tricks have to be learnt. Would you like to say something about how this is a reflection of South African society’s attitude towards womxn and the normalization of womxn constantly feeling unsafe? Perhaps you could expand on your statement that this “hyper-awareness is a form of oppression” in discussing this?

In Nightfall I want to show the fundamental difference in how men and womxn access space. Large, open spaces can quickly become claustrophobic as womxn employ certain tricks to avoid entrapment.These tricks can be a matter of survival. Womxn move through public spaces deliberately and with all their senses heightened. We swerve from side to side trying to avoid potentially harmful encounters. We tug at our skirts, pulling them down and squirm as if we want to crawl out of our own skin. Many of us use the Good Ole’ Earphone Trick to avoid having to make contact with men around us. As if these earphones could magically act as shields against their unwanted advances. Usually there is no music playing – their use is just a silent prayer to be left alone. We live in a constant state of fear, and this fear is so interwoven in daily lived experiences that it begins to feel normal.

The double-edged sword is not only are we unsafe in public places, but also are blamed for not keeping ourselves safe. We’re told our dresses are too short, that we are asking to be harassed, that we should’ve been more vigilant when all we have been is relentlessly vigilant. This hyperawareness oppresses us in that it prevents us from living freely and fearlessly. We are somehow always told we’re complicit in our exploitation. Not even the burden of hyper awareness can save us from our bodies being sacrificed to maintain and strengthen patriarchy. It seems all spaces that are not specifically marked for women (toilets, baby changing rooms) by default become male dominated spaces. Nightfall is a direct affront to this domination.

Tell our readers about the decision to translate this into a performance piece in which you use bricks as a physical representation of this oppression?

Bricks symbolise heaviness and the immovable. I wanted to focus on the psychological heaviness of being a womxn. We navigate the world aware that we are unwanted and that we will face challenges at every corner – a persistent heaviness on our psyches. The four bricks, two tied to each foot, represent the weight society places on us to survive. Every move we make is scrutinised. Our oppression is our burden to carry. I wanted to give the invisible weight we womxn carry around a physical manifestation. Once we see things we are more likely to believe them. It’s easy to ignore the invisible, but harder to ignore a female body being literally being weighed down with bricks. The performance needed to be physically challenging to adequately represent the challenges womxn face. And let me tell you trying to walk around with bricks attached to your feet is no mean feat. I couldn’t walk for 3 days after that! I fell down many times and this again is a metaphor about how women face challenges but are expected to carry on to survive. During my last fall about 20m from the intended “finish line†I cut my knee open with blood gushing down my leg. How poignantly accurate of how grueling a womxn’s journey can be.

Tell our readers about the clothing choices for this performance and their significance?

As someone who is well acquainted with certain areas of the sex work industry I wanted my clothing choices to reflect as sex worker positive. Fishnets have long been associated with sex workers and the aim here was to reclaim them as a positive symbol of powerful, resilient womxn. I’m a proud “nasty woman†(no thanks Donald Trump). Sex workers, especially WOC, often experience grave violence enacted on their bodies. As a society we need to protect and uplift sex workers. Sex workers also often wear items to mask their identity and protect their anonymity; it is a performance. The eye popping pink and leopard print bodysuit paired with the elaborate platinum blonde wig references stage performances and highlights that femininity is performed. This exaggerated performance points to the instability of gender identity. On an aesthetic level the bricks reference high heels sex workers often wear. Often in my performances (see Hollywood Cerise) I choose to be hypervisible yet incapacitated to a certain degree to call attention to how women are hypersexualised, but prevented from accessing power. Hypervisibilty is where we are constantly watched but not seen. Being seen implies validation, while being watched is an unwanted gaze. This gaze is exploitative and does not seek to empower womxn. Nightfall exposes this unwanted gaze and manipulates it so the viewer is forced to interrogate their own motivation for looking.

The name of the performance Nightfall also reflects on the increased hyper-awareness that womxn need to engage in to be out at night. Would you like to say something about the experience of the performance, particularly how you felt as the day was turning to night and knowing the kinds of anxieties that darkness can bring for womxn.Â

Womxn’s anxieties are often compounded. Say for example a womxn is walking through a public space, this in itself can already be considered dangerous, but add to this the element of nightfall and a group of men and suddenly her chances of being preyed on are maximised. Nightfall started in the early evening while it was still fairly light, and as the performance progressed nightfall descended. With the darkness comes increased awareness, and increased opportunities for womxn to be preyed on. It was on a night like this that Nokuphila Kumalo was brutally murdered by well known South African artist Zwelethu Mthethwa. Nightfall is a requiem to all the womxn who have been silenced.

There has been an increase in the number of stories of womxn being abducted and murdered in SA over the past few weeks. I think your work speaks to the need to address the kinds of structures that continue to be at play that allow for such tragedies. How do you situate your work within these kinds of conversations?

Female visibility in the media is always strictly controlled and we have to ask ourselves, are these kind of stories more prevalent at the moment or are they just more visible. Womxn are always stuck in this endless limbo between being invisible and hypervisible. Nightfall is a direct response to the violence womxn face daily. My work aims to open up a dialogue where those who are often silenced can finally speak and be heard. I look to the work of female performance artists like Emma Sulkowicz who after experiencing sexual assault on her campus carried her mattress on her back until the end of her semester (including to graduation). This endurance performance involved in Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight) speaks to me and relates to the burden of the bricks in Nightfall. Our bodies are both the weapon and the battlefield in this gender war.

These stories have been accompanied by ongoing #menaretrash and #notallmen debates on social media and in person. Reflecting on your performance and the premise that it is based on, what is your take on the directions that these conversations have taken? Perhaps you would like to refer to specific comments you have heard or social media engagements you have seen/been part of?

Women face micro-aggressions every day. From so-called flippant comments online, slut-shaming, victim blaming and of course my personal bête noire mansplaining. Many of the comments that I have seen from men in this online space (#menaretrash) is that women need to “learn to take a jokeâ€, or not take themselves “too seriouslyâ€. What we need to understand is that there is a direct correlation between words and actions, and they can’t be separated. Words, so called “jokesâ€, directly lead to violent actions against womxn. There is no way around this. It saddens me that some men have no understanding that misogynist jokes and microagressions are the premise on which greater hate against womxn is built. So, yeah, #menaretrash.Really what I’m looking for when men engage in these conversations is accountability. Accountability for the violence against us, and holding their peers accountable for objectification. The #menaretrash conversations is an affront against rapists, murderers and misogynists, but also against those who stay silent while we suffer. Nightfall creates a space where I have full-ownership over my body and can wield it how I choose to, unlike in the daily identity performances where womxn are sidelined.

Lastly, would you like to say something about the use of ‘womxn’ and the momentum of its political power?

It’s 2017 and we all need to work together and demand more inclusivity in our media and representation. The use of the term “womxn†is just a small way we can be more inclusive of our trans sisters and assert that we are not merely extensions of “menâ€. These are our stories and we’ll use our language, please and thank you.

Anything else you would like to mention about yourself or your work? Any particular links you would like to share?

I don’t see this performance having a start and end date. I would like to take this performance to more public spaces, as I feel the message is powerful and is something especially men need to be confronted with. I want to use my body to advance conversations. Our work is never over until women stop being unnecessarily persecuted. Our bodies, our performances, our words, our art can be a catalyst for social change. I have to believe that to survive. I’m not giving up and neither should you.

To see more of Jana’s work visit her Tumblr page or check her out on Instagram.

She would also like to encourage people to support and donate supplies to South African Sex Workers.