Over December, Johannesburg is a city that empties. Residents escape to their family homes or holiday beaches, leaving the once-bustling metropolis surprisingly quiet. The Eastern Cape experiences a reverse effect as its towns and villages swell with relatives returning home. In Port Elizabeth, one of these returnees is Siyabonga Ngwekazi, who most of us know as Scoop Makhathini.

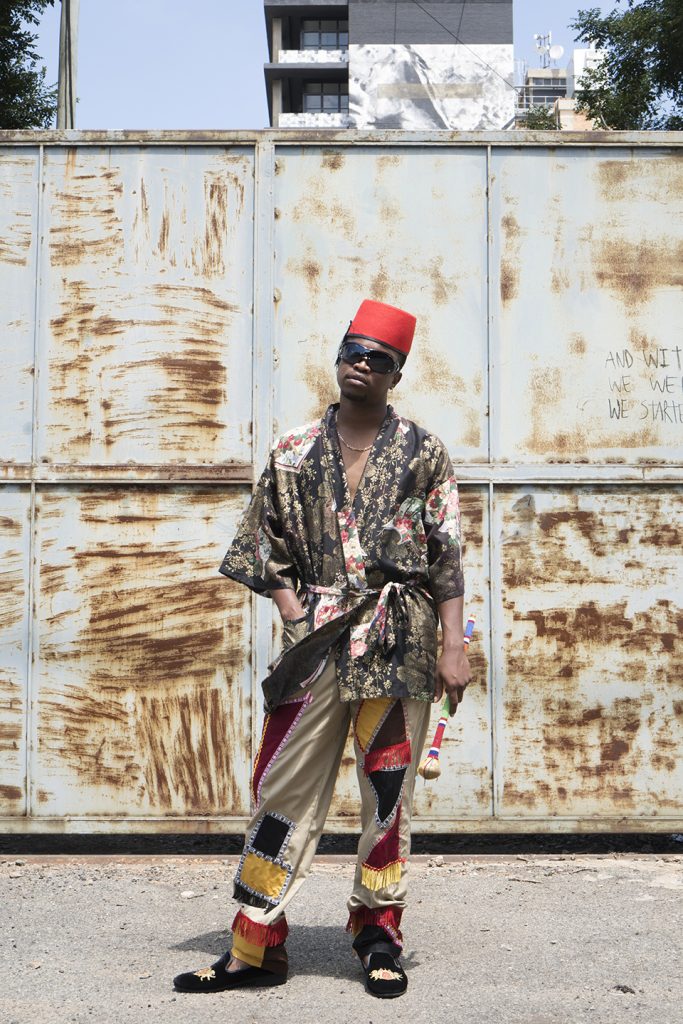

A prolific television presenter, and a high priest of South African street culture, Scoop serves as a cultural medium, a multi-spectral prism of the country’s street artistry.

‘Music and the arts, they come from this place that’s very godly, very heavenly’, Scoop says. Like any other medium, his talent has been to interpret the divine for an everyday audience; to draw linkages between past, present, and future; and to serve as an interpreter for the creative world.

“I think that’s why I’m here — it’s to take these pieces, or blocks, of creative South Africa. Because I understand where they’re coming from. And I can chop it up into little bite-sized pieces for your mainstream audience to understand to be able to digest: to be able to understand the weird crowd, the off-centre crowd. In a medium that’s easy to them. Most creatives can’t speak about themselves. They can’t explain. It’s hard for them because they feel like they leave it all out on the canvas, or they leave it all out in the sculpture, or they leave it all out in the track. So analyzing them and getting someone to understand, ‘Oh this is why this person paints like this or uses these colours. Oh I get it. It’s also relatable to who I am’â€.

Often there is a chasm between Scoop’s TV audience, and the creative world he spends his time in, where so few people access media through television. His ability to reach across this gap, to a multiverse of audiences, is part his own artistry. “Anyone can be a TV presenterâ€, Scoop says, “but it’s about ‘What are you saying? Who are you speaking to?†In presenting, Scoop not only showcases local creativity to a mass audience. In doing so, he also interprets it, diagnoses it, and drives some of its biggest trends.

Part of what allows Scoop to translate across diverse peoples and places is that he, like so many generations of men before him, moves in a cyclical way from Johannesburg to the Eastern Cape, and back. Siyabonga grew up with three siblings. His mother was a teacher and his father a truck driver. He talks vividly about the bleak representations of black men in his 1980’s neighborhood: “the emerald green hat, the blue overalls, the checkered shirt, the denim jeans, and finally, “that bootâ€. “Those brown army boots with the steal toe that dads used to wear for MK or marches or toyi-toyi.â€Â

Amidst all this, Siya dug his dreams into hip-hop and basketball, reaching through his television screen for portrayals of powerful blackness, thousands of miles away. “Rap and [American] sports were the first time in the 80s you saw a black guy look like something. You saw guys with the cars and the clothes and the jewelry and the girls and the confidence and the bravado. That’s when you knew the difference between America and South Africa. And even though they were oppressed, at least they could be this.†It’s clear that from very early in Scoop’s life, clothes, television and street culture carried powerful identity politics, and emancipatory potential.

Today, Scoop has 12 years of industry experience under his very-fashionable belt and a blossoming career.

As a trend-spotter, pioneer, and supporter of the country’s creative industry, Scoop’s notoriety has come from his ability to bring attention to others. “I think it’s because when I started getting cred, I never kept it. I see who’s next. I hear who’s next. I’ve seen what notoriety can do for someone’s life. Be it bills, or be it the confidence, or be it helping out the familyâ€.

But there’s “this thing in Jo’burgâ€, he told me: “hoarding the propsâ€. “People are very scared to tell someone how good they’re doing, or how that person inspired them, or how they’ve got respect for that personâ€. All for fear of losing their position. “When there’s nothing, it’s amazing how close everyone gets. But as soon as a breadcrumb lands in between two people, watch them scramble in the dark to find a crumb. Not even look for the loaf. Or the bakery.â€

Scoop’s vision now is retrospective, focusing his prism on the knowledges of his ancestral past. “I’d really like to be home in Port Elizabeth, learning about how to slaughter a cow, how to clean its insides. From birth to death, I need to be able to recite which ceremonies need to be done, which liquor is needed, which rooms certain things are kept in.â€Â

Always a medium, Scoop’s own reflections serve as a refracted mirror of a generation — their conflicts and their creativity.

“I [like so many others] have learnt about Jordan’s and Nike which has nothing to do with me! I’ve been to a school where all I’ve learned has fuck all to do with me! So I just want to learn about me. It’s been such a long road travelled now. What I’m really yearning for is to stay next to my father and have him teach me how to be black again.â€

For Scoop, the biggest risk to the creative industry is the loss of self. Especially since, “the creative realm is just a realm in search of self. These kids think they’re searching for a label or a t-shirt. Everybody’s just searching for themselvesâ€. And that ‘everyone’ includes Scoop Makhathini himself.

“I go to PE and it’s always where I learn how far I’ve drifted from being a normal personâ€. It’s clear that despite being a celebrity, and having unique access to ethereal artistry, Scoop remains deliberately (and sometimes controversially) committed to his own messy personhood. His Twitter feed and his show ‘Forever Young’ offer intimate access to Siyabonga the person, beyond Scoop the persona.

“I think it comes from a place [of] just wanting to be a human being, to experiment, to have views, even though they’re wrong. So often [in the industry], people have to fight to get liked. Everyone likes being liked, but I think I also like being disliked, because at least then I don’t have to retain that approvalâ€.Â

Although we expect celebrity role models to strive for exemplary leadership, there is something powerful in Scoop’s embrace of the imperfect: it gives others the audacity to lead when they might have once have been off-put by the pressure to be faultless.

Like so many mediums before him, Scoop often speaks in metaphor. “I just like swimming upstreamâ€, he says. “There’s not much to discover if I go that way with everyone else. There’s not much to discover about myself, about the world that we’re living in, about the people around meâ€. And that is what creative ‘success’, he believes, should be about. “What really pains me?â€, he says. “We’ll excel at so many things, but we will not excel at being ourselvesâ€.

Photography by Jamal Nxedlana

Assisted by Lesole Tauatswala