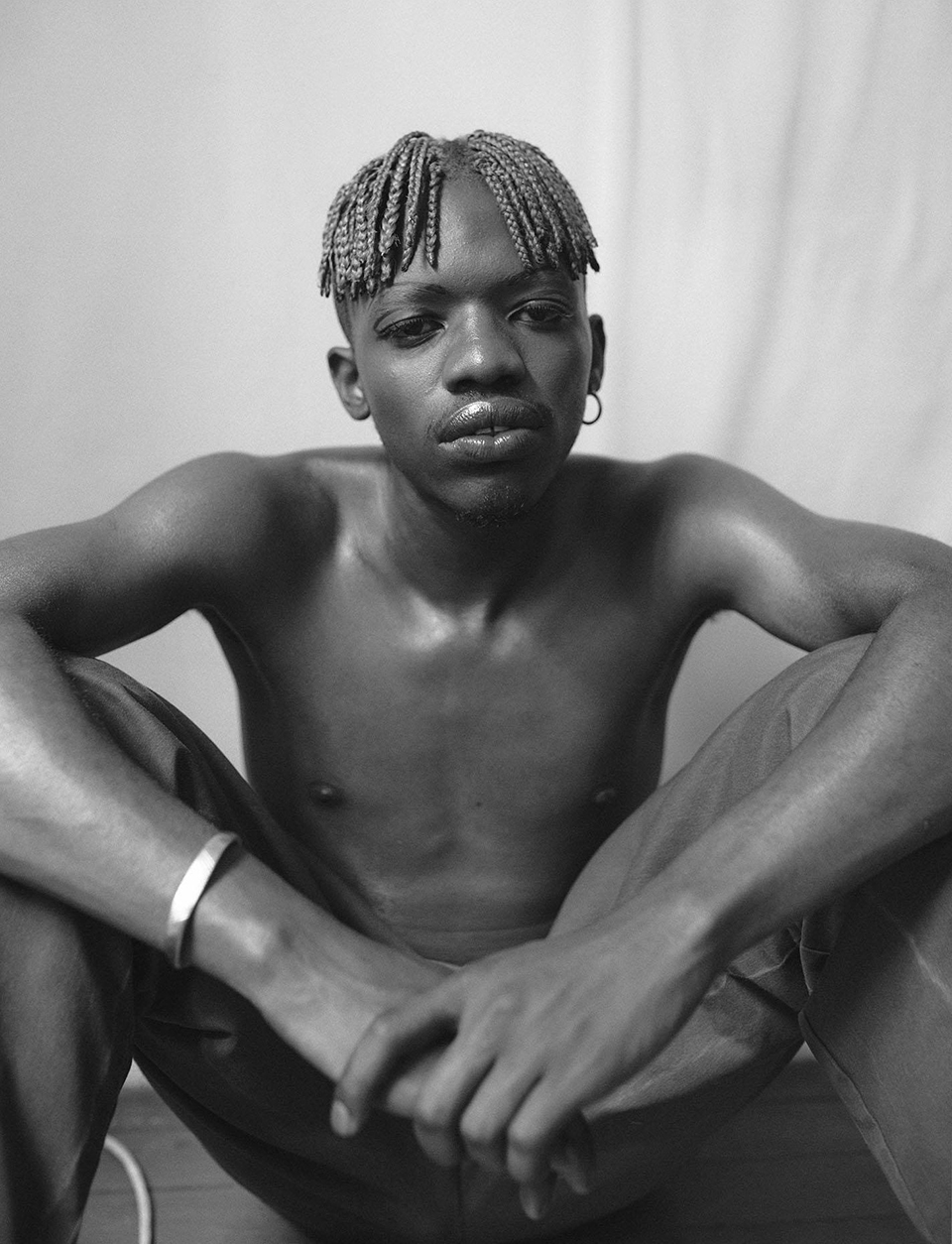

Three months ago, I shared 90-minutes with Buyani Duma (otherwise known as Desire Marea, of the artist collective FAKA). Encased in a wall of glass at the Newtown Workshop, we moved unusually quickly from strangers’ niceties to buried intimacies. A few weeks later, on a Juta Street corner, Didi Simelane (A.K.A style icon Didi Monsta) and I were exchanging histories for herbal tea. In each of these conversations there had been a moment in which the artist seated across from me seemed to leave our city meeting spot. As if speaking from a suspended television screen, their voice emanated like static through flickering colour bars, projected either from a nostalgic past or a utopian future, or maybe both. I sunk into those seconds of being lost, basking in the aesthetics and poetics of someone who moved in another plain. But I haven’t been able to write about either conversation since. Over the past few days, Didi and Desire have started to speak with one another inside my head. I don’t know if they’ve ever met, but, in my own mind, Marea and Monsta were performing a collaborative pantomime.

Didi grew up in Pretoria, also spending many years of his childhood in Mozambique. A designer, style icon and influencer, he says he’s always been fiercely experimental in his style. Didi remembers how his mom used to put him on the ‘next next vibes’. ‘Sneakers wise, clothes…’ he told me, ‘she would buy clothes for me as if she was buying for herself. She would go so Rambo on my gear. Me and my brother. Yeah, she would go Rambo. I would just kill everybody’s style from a young age.’

Desire describes himself as a ‘village boy’ from KZN. Reflecting on his after-dark upbringing he said, ‘I liked going to the tavern and just dancing. That’s my nightlife there and it’s intense. I love it’. Didi has found inspiration in the night too, hence his brand ‘3am LifeWasNeverTheSame’. Meanwhile, Desire has been engaged in a different project: the cultural movement, FAKA, have sought to create a visual and performance archive, testifying to alternative expressions of black queer identity.

Having each recently moved to Johannesburg, both Didi and Desire have a story to tell about the city’s party culture. In their own way, each artist describes the night as a cloak, masking our shared brokenness, and delimiting the modes of expression acceptable for the dancefloor. ‘We end up covering ourselves, you know’, Didi said. ‘We go partying. I’m not saying there’s something wrong with partying, but just partying, there is something wrong. Me forgetting my purpose.’

Desire also paints a picture of a prescriptive party-scene that alienates us from who we are. ‘There’s a lot of pressure in spaces like Kitcheners or Great Dane, where you have to be a certain kind of cool. I don’t know — there’s that thing. And Cool Kid is also very narrow by definition, in that context. It’s only a certain kind of cool and it shuts down every other cool.’ The assumption is that when you’re there you’re that. The space is that loaded’. The club space imprints itself upon you, requiring you to wear a particular kind of mask.

‘We do get very lost’, Didi says. ‘It becomes fun. It’s fun. But it’s not fun. So it’s like you’re there, but you’re not there’

Social theorist, Zygmunt Bauman, says that masks permit ‘pure sociability’, detached from circumstances of power or the private feelings of those who wear them. We take on ‘masks’ in the hopes of protecting others from the burden of ourselves, and making interaction possible..

Desire uses the term ‘Nivea-ness’ to describe these forms of social masking. ‘Nivea-ness’ means embodying a ‘polished’, superficial persona as an act of self-protection. Much of Desire’s work has been to comment on and explode stereotypes on the gay scene. Here, Niveaness ‘is your cis gender metrosexual, who wears head-to-toe Markhams. He stays in Sandton or in a Marshalltown bachelor pad. Very invisible but carrying a lot also. Carrying a lot, but giving off this ‘best foot forward’ kind of vibe. The fact that you are ‘Nivea’ over like Vaseline’.

Bauman would call this mode of interaction ‘civility’. Putting on a mask means disguising our personal demons, and we expect others to do the same. We don’t expect to be cajoled into expressing our inner-most feelings in public spaces. Instead, we take on a ‘persona’ that enables us to share crowd space. This is the ‘civility’ that the city requires. And while Didi and Desire may occupy different worlds, they have a shared ability to identify the city’s masks.

In his poem, Johannesburg, Abdul Milazi writes:

Welcome to Johannesburg

where we wear our nightly masks

our private pain stored away

to be dusted and worn again at sunrise

For Didi, there is frustration in being approached always as a ‘public persona’, rather than a person. ‘Aren’t you the guy from that magazine?’ they’ll say. ‘I think you should greet people first, you know. But cats jump on: ‘Yo, yo!’ But you don’t know me man. If you come inside a room you should knock before you go in. You greet. We all humans you know. Before I’m an artist I’m a human being. I go through things as well. Maybe I’m not in the mood. Maybe I’m not having a good day’.

Beneath our surface appearances, Didi explains, is a deliberately concealed wound. This has been the impetus behind Very Lost — a playful autumn collection of outwear. ‘We’re all broken’, Didi says. ‘It’s just about every human being, being broken at the end of the day. And not talking or not finding somebody to help them. There’s something that happened to you as a child. Maybe they used to bully you, then you grew up and started bullying other people. Maybe you’ve been raped, maybe you’ve been molested you know. We end up covering ourselves’.

It resonated so strongly with something Desire had written a few weeks before: that ‘everyone on the Buffalo Bills dancefloor, still or mobile, is essentially an adult who was once a child, who was probably teased, who probably hated themselves…’ In a story for Bubblegumclub, Desire wrote about the unravelling of intimacies and traumas between two strangers on a night out. He explained to me that the club-goers he met, no matter how ‘hard’ they might try to sell themselves, were ‘just so soft. We’re all so broken and vulnerable.’How do we give that a voice? Desire practices art as a route to humanising oneself and others. It is a humanising process that he profoundly and paradoxically articulates as ‘godliness’. Without masks, ‘we’re not actually strangers’ he says. ‘As much as you don’t know others, you do know them.’

Because there’s so much fragility to hide, people become all the more keen to guard the space and protect their own boundaries.

‘There’s this social hierarchy that’s really bothering me’, Desire says. ‘So like a person who goes to a tavern can’t really access Kitcheners. And not by choice. The people that go there would probably stop going there if the audience changed radically. It’s very territorial. Model C kids are very territorial.’ For Desire, compounding this classist element are prescriptions about the modes of sexuality that one is able to express. ‘Femme bodies are still more shamed. Femme bodies are not allowed to express their sexuality in the same way.’ So while ‘civility’ might provide a volatile safety for some, it is also violently prescriptive for many others. ‘

‘People have an issue with the power to transcend’, Desire says, because everybody’s oppressed in a way. I guess when you’re a person who’s oppressed, the world as it works doesn’t allow you to be beautiful, doesn’t allow you to be amazing, doesn’t allow you to be great. If you are actually a black person who’s great and amazing, or who feels like they’re great, that’s intimidating. We’re not supposed to exist. But we do! And it scares them’.Â

Both Didi and Desire fearlessly push their audiences by embodying this transcendental space. For Desire, this means unravelling and presenting a provocative kaleidoscope of queer masculinities. For Didi, it’s bold ‘back-to-the-future’ threads that explode the bounds of status-quo style. Whether in biker gear, old-school vans, camo or overalls: Didi’s sought-after swag has imprinted ‘next level’ aesthetics on hip-hop videos and stages, look books and dancefloors. ‘Sometimes I’m too forward man’, Didi says. ‘It’s like, yoh I see it happening the following year. I’m on the next, 24/7’. Both artists, for all their differences, are unapologetically themselves. As Didi says: ‘There’s no I’m gonna be a social worker. There is no, I’m gonna be a doctor. This is what I do’.Â

Each artist comes ready to wear their non-conformity in the times and spaces that might provoke ridicule for it. ‘I know people that were laughing at me four years ago, trying to jump on what I’ve been doing, now’, Didi says. This is the work of being, what we so casually call, a ‘trend-setter’. You live in a yet-to-be space, as though it already exists. And from this precarious not-yet-existing place, you call others to you. Speaking through the (too-often literal) white noise, drawing us to the honesty and audaciousness of our flickering, glitchy humanity.

If Didi’s clothing concept Very Lost, could speak, it would say: ‘Do something. Stop with the masks, man’. By encouraging us to wear our ‘lost-ness’ on the outside, the collection injects this challenge with urgency and daring. ‘Everybody’s tryna be on the scene’, Didi says, ‘But then what’s your function on the scene? What are you doing on the scene? So many cats miss the mark.’

Whether explicitly or not, the function of both Desire and Didi has been to disrupt. For Didi: insert pastel pink and playtime camo into a hard grey cityscape. For Desire: insert black queer bodies into an oppressively hetero-normative space. In both cases: insert fearless fragility in place of artificial mask. And watch art happen.